Somali refugee woman reunites with children after 10 years

Somali refugee woman reunites with children after 10 years

VIENNA (UNHCR) - When Zahara (not her real name) decided to become a police officer, she did not think that one day she would be the one needing protection.

Zahara grew up in Burao, northern Somalia, as a member of the Darood tribe. Her mother died while giving birth to her and since her father could not take care of her, she had to stay with different relatives, which was not always easy. "When I complained to my father that the uncle or the aunt I was staying with wasn't treating me well, he would just take me to another relative. And sometimes the situation would just get worse," says Zahara.

Eventually she got to know a girl friend whose parents became like a foster family to her. When the girl's father, who was a police officer, asked if Zahara would like to follow in his footsteps, she jumped at the opportunity.

Soon after she finished police school, Zahara met her future husband, a medical doctor. Despite the objections of his family over tribal differences (he is from the Hawiye tribe), they got married and moved to Mogadishu. Within the next five years, Zahara gave birth to five children. But the tense situation with her in-laws remained. "I always felt their hatred towards me. But I thought as long as my husband stood up for me, I could live with it," she says.

In the beginning of the 1990s, shortly after her youngest daughter was born, tensions between both tribes escalated and led to a civil war that tore the whole country apart. "It was horrible," says Zahara. "All Daroods fled from Mogadishu, but I couldn't leave. According to Somali law, my children are Hawiyes, and under no circumstances did I want to leave them behind."

One evening, in the summer of 1992, shortly after Zahara's husband had left the house to visit his father, six armed men entered the house. "They started to beat me up in front of my children and requested money and gold," she recalls. But money and gold were not enough. They dragged her into a room and raped her. As she kept on defending herself, one of the men stabbed her severely with his bayonet. Her attackers only fled when her neighbours, who were alerted by the children's screams, came running.

"It was clear to me that my life was in danger and I had to flee from Mogadishu," says Zahara. "The worst thing was that I didn't know if I would ever see my children again." She found shelter at a friend's house in Jilip, 300 km north of Mogadishu. Even though she only intended to stay there for a short time, it took three years before she was able to flee the country. "Throughout the whole time I hardly ever dared leave the house because I was so afraid something bad might happen to me again."

With financial help from a friend who had already fled to Europe, Zahara was able to pay for a false passport. Via Yemen and Hungary she made it to Austria, where she arrived on September 12, 1995. She applied for asylum the same day but her application was rejected within a few weeks. Furthermore she was denied any assistance provided by the Austrian authorities, and ended up homeless.

Luckily she found a social worker from CARITAS who not only assisted her in her appeal procedure but also gave her some financial assistance. For one year, Zahara stayed in a shelter for homeless women, where she shared a room with three other women. After that, she was able to find a place in a refugee shelter for homeless asylum seekers.

Whenever she managed to earn a little bit of money, she would call her children in Somalia. "It was terrible, one minute to Somalia cost almost US$3. Of course, every child wanted to talk to me, and with six desperate children, half an hour went by like nothing", says Zahara.

Sometimes she could not pay the bill at the end of the call. "I would leave my watch at the post office, run home and tell the people at the refugee shelter, 'Please, please, I urgently need some money!' After some time the guy at the post office got to know me!" she laughs.

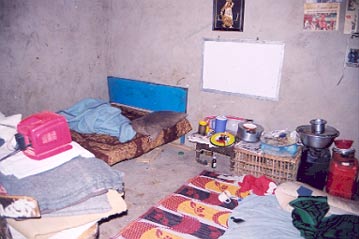

Even though she was grateful to have a roof over her head, the long years of having no privacy had a serious psychological impact: "I just couldn't stand it any longer," she says. With the help of her social worker, she was able to find a tiny apartment, which was in a terrible condition, but where she could live on her own.

In October 1999, Zahara had a second interview regarding her reasons for flight. "After that, I thought I would get a decision soon, but I was waiting and waiting and waiting." It took another one-and-a-half years before she finally received the decision.

"When the postman brought the letter, I was so excited that I couldn't understand what it said. Was I granted asylum or not? So I ran out into the street and asked a passer-by if she could tell me what it said. She studied it for a long time and finally said, 'This means that you can stay in Austria!' I started to cry and threw my arms around her." Altogether, she had to wait five-and-a-half years for her recognition as a refugee in Austria.

Her new status grants her access to vocational training. She started right away with a German course, and after that, trained to become a nurse. "I finished the course on December 21. All the other participants wanted to start working after the Christmas holidays. But I said, 'The examinations are in the morning, can I not start working in the afternoon?' Well, I couldn't start the same day, but the next. I was so happy that I was finally allowed to work."

But the most important thing for her was that she was now allowed to bring the youngest four of her six children to Austria. Nevertheless many practical obstacles had to be dealt with first. The children, for example, did not have any travel documents and were not able to obtain any due to the situation in Somalia. Only with the help of UNHCR were they able to receive provisional travel documents with which they travelled to Nairobi, and from there on to Austria. On January 23, 2003, Zahara was finally able to hug her children again after more than 10 years of separation. Her youngest daughter had blossomed from a two-year-old toddler to a 12-year-old girl.

After the long years apart, she and her children need to get to know each other again. Furthermore the children have to get used to a totally new culture, language, schools and friends. Challenges still lie ahead, the saddest being the fact that they remain separated from the oldest two of Zahara's children. According to Austrian law, they are not allowed to reunite with their mother as they are already over 18 years old.

"Whatever will come, nothing can be as bad as being separated from my children," says Zahara. "I will not give up fighting for the day when my two eldest daughters can also come to Austria."

By Sabine Racketseder

UNHCR Austria