A "non person" with a big personality

A "non person" with a big personality

CAIRO (UNHCR) - Berjouhi Bakalian has given up a showbiz career and a marriage proposal so that she can stay in a country that doesn't recognise her existence. Asked why she made these sacrifices, the 82-year-old woman says, "There is no way I could leave the only home I've known, Egypt. I couldn't live anywhere else."

Bakalian is one of the 100 stateless persons living in Egypt under the care of the UN refugee agency, and one of millions of stateless persons around the world.

According to the 1954 Convention relating to the status of the stateless persons, a stateless person is someone "who is not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law". Often, he or she does not have a national identity document, and has poor access to the basic social, economic and political rights of a citizen. One expert describes them as "non persons, legal ghosts".

In Egypt, there are three generations of stateless persons. The first consists of those who came between 1914 and 1926 after fleeing the atrocities of the Armenian genocide and the First World War. The very few who are still alive are in their 90s and in poor health.

The second generation consists of persons in their 70s and 80s. Many of them are single and lonely as their children have immigrated and abandoned them.

The third generation consists of younger persons who are facing many problems because of their statelessness. They are treated like foreigners under Egyptian legislation and do not benefit from any provisions of the 1954 Convention, of which Egypt is not a signatory. They thus have to face the hardship of being stateless in addition to the high costs of health care and obtaining a work permit.

Coming from different backgrounds, the majority of them of Armenian, Albanian or Russian origin, each stateless person has his or her own tale to tell, but they all share one burden - they have no home to return to.

Born of Armenian origin in Turkey in 1922, Bakalian lost her father during the genocide against the Armenians. Her mother took her to Egypt and remarried soon after. Bakalian's stepfather sexually harassed her, and to solve the problem, her mother married her off a 50-year-old man when Bakalian was just 18.

Her marriage was full of misery and humiliation as her husband often abused her. "The only good thing that came out of my marriage was my son, but after 13 years of pain and humiliation, I couldn't take it anymore. I ran away," she recalls.

She found a job at a hotel, cleaning rooms and working in the kitchen for several years before her boss sold the business to move back to Greece. Although he offered her a job in Greece, she refused to leave her beloved country.

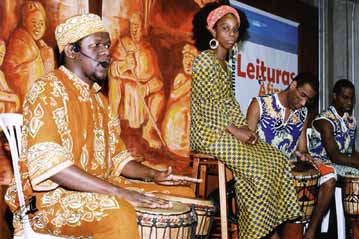

A few years later, she visited her half brother in the United States and ended up staying, performing in San Francisco's theatres for two years. "I was very pretty at that time - don't look at me now - and I loved to dance. I was very good on stage," she recalls excitedly.

But she gave it up for a cooking job in Cairo, explaining, "This is Egypt and I can't leave it no matter what."

Back in Egypt, she fell in love and got engaged to an Armenian man. But his mother objected to their marriage and he had to leave for work in the United States. He begged her to join him but again, she couldn't leave. "He used to send me letters all the time. I would read them and cry."

Bakalian first registered with UNHCR in 1967 after hearing about it from a friend. She started receiving assistance from the refugee agency's implementing partner, Caritas, in 1975.

Before I meet Bakalian for the first time, Caritas director Soheir Fawzy shows me a picture of her as a young woman and I have to admit I am impressed by her beauty. There is something about her that speaks of pride and dignity.

As we climbed up the stairs to her apartment, Soheir explains that Bakalian fears strangers and refuses to open the door to people she doesn't know. As we knock on her door, we hear a frail voice calling from inside, "Who is it?" and the sound of dragging feet approaching.

The door opens to reveal a cute chubby lady in a burgundy house dress. And as I look at the face I saw just moments ago, I see a trace of her former beauty. She squeals with joy that someone has come to visit.

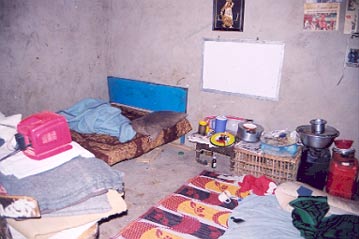

Her humble home consists of a small sitting area with a single couch and a plastic chair that were given to her by one of the neighbours who no longer had a need for them. A small bulb dimly illuminates the entire house. She fears that using stronger bulbs will end up costing more, and with a monthly allowance of LE 300 ($48), she fears she may not be able to afford it. Nonetheless, she thanks Soheir for the monthly allowance she receives: "I don't know what I would have done without it."

The only family Bakalian has come to know is Caritas and the social workers who bring her the monthly allowance. "I want to live in Caritas," she says. "You're the only people who ever ask about me."

When Soheir asks about her son, the old woman's face turns red with fury. "I have no son, he hasn't asked about me in years," she says. "His father convinced him that I'm a bad woman because I walked out on them. But I had no choice."

Although Caritas made several attempts to convince him to visit her, Bakalian's son signed an official document saying that his mother is dead.

Despite her sad history, Bakalian laughs with joy at the funny comments we make. But she pauses to say, "I swear to you I am scared all the time. I keep thinking that burglars will come in and kill me. I can't help but think these bad thoughts throughout the day when I sit here all alone." With no television or even a radio to break the silence, each day seems like an eternity.

Still, being the kind of fighter she is, she tries to get out of the house as much as possible if her health permits. "When I need to go out and buy my food, I wait at the stairs until I hear someone leaving their apartment and I call out for them to help me down the stairs." Once she is out in the street, she often passes by the shop of one "Farouk" to watch his TV.

In her old age, Bakalian still cares a lot about her looks and pays a lot of attention to her appearance. It takes me a long time to convince her to pose for a picture. She asks for time to prepare herself, taking a small mirror and a red lipstick out of one of the plastic bags surrounding her bed. Then she puts on a hat, "to cover the white hair," she explains.

But two pictures are all she allows me to take. "What's there to photograph? You should have seen me when I was young. You would have liked me a lot," says the feisty woman.

She may be classified as a stateless person, a "non person, a legal ghost", but to me, Bakalian is a real and amazing person whose thirst for life and love for her country deserve much more recognition.

By Amina Alkorey

UNHCR Egypt