Vietnamese local governments smooth the way for stateless Cambodians

Vietnamese local governments smooth the way for stateless Cambodians

THU DUC, Viet Nam, November 8 (UNHCR) - Not so long ago this marshy area was considered remote from Ho Chi Minh City, accessible only by boat. Today, as Viet Nam charges ahead as the latest Asian tiger, Thu Duc has been incorporated as District Nine of the economically vibrant, rapidly expanding metropolis.

And as small boats are replaced by wide bridges, and rice paddies give way to new roads and buildings, the city fathers - gripped by construction fever - have their eyes on land occupied by homes that the UN refugee agency built more than two decades ago for Cambodian refugees from the brutal 1975-79 Khmer Rouge rule.

"We have to urbanise this area; this is the policy of Ho Chi Minh City," explained Le Trung Sang, chairman of the District Nine People's Committee. "So we have to relocate these people."

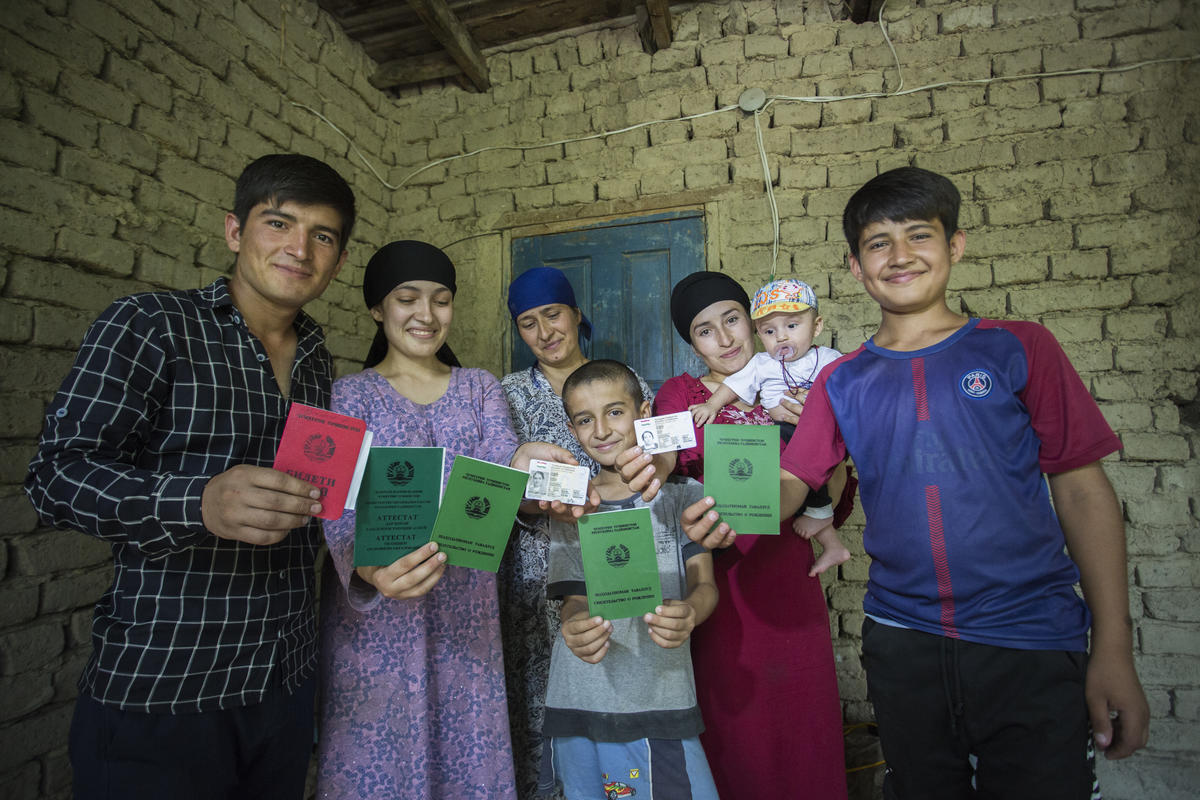

For the Cambodians, most of whom are now elderly, the prospect of leaving their homes is grim enough. But their fears are compounded by the fact that they are stateless and have no legal claims to whatever compensation their Vietnamese neighbours might get in the eviction.

In an act of compassion, the district authorities decided to treat the stateless Cambodians the same as the local people, and are now preparing homes for those who will be displaced to make room for a school. It's just one example of how local authorities are endeavouring to make life simpler for the 9,500 former Cambodian refugees now living in and around Ho Chi Minh City.

"It's very important for these people to get Vietnamese citizenship, so we can better solve their social problems," said Tran Phuoc Hung, chairman of the Long Phuoc commune in District Nine, while also noting: "We have no concrete policy from the central government or city."

UNHCR is encouraging the Vietnamese government to solve the problem by offering citizenship to the exiles. "I find the plight of these people very emotional," says Hasim Utkan, UNHCR's regional representative. "I come from a culture that respects old people, and it's very sad that at the end of their lives all these people want is to be able to pass on to their children the most basic of rights - the right to citizenship and identity."

These stateless people, many of whom were Cambodians of Chinese ancestry, were left high and dry after Vietnamese forces toppled the Khmer Rouge in 1979. Having lost their identity documents and then having settled in Viet Nam, they were disowned by their own government.

Community leader Quach Trung Thanh knows only too well the Kafkaesque loop in which the former refugees find themselves. "According to the laws of Viet Nam, we have to renounce our previous nationality to get a new one," he explained. "But when we go to see the Cambodian consulate in Ho Chi Minh City, they say we are not Cambodian citizens."

There are other problems. "In the past, the authorities issued temporary birth certificates for children born in the camp," said Thanh, now 70. "But now the children are grown up and they need to have a formal birth certificate. But to get a formal birth certificate, you have to produce a marriage certificate, and we are not allowed to have a marriage certificate because we are stateless."

Without legal title to their land, they cannot use it as collateral for a bank loan. Locked out of legal jobs because they lack the all-important state ID card, they are consigned to low-paying jobs, with no recourse if they are unfairly treated.

"We have no rights at all," said Thanh, who praised the efforts of local authorities to treat them equally with citizens but added that, "Outside this commune we need formal legal status, which we do not have."

Tran Tai, 72, knows how tough it can get. His 29-year-old son, born in Viet Nam, has been unable to register his marriage three years ago to a Vietnamese woman because the Cambodian consulate refuses to certify that he is of Cambodian origin and single. "Our people can still get married, but without a legal certificate," said Thanh.

Thanh finds it hard to understand why Viet Nam - at the central government level - will not legally accept this group of fewer than 10,000 people with deep ties to the country. "Everyone understands me and everyone knows me. But actually I am nobody here. We are some kind of second-class people," he said.

By Kitty McKinsey in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam