Protracted Refugee Situations: Bangladesh camp life improves, but home is best

Protracted Refugee Situations: Bangladesh camp life improves, but home is best

KUTUPALONG REFUGEE CAMP, Bangladesh, December 10 (UNHCR) - When Hafez Jalal Uddin first fled his native Myanmar in 1991 and sought refuge in Bangladesh, he resisted going to a refugee camp for three years. When he did finally register as a refugee, he was at first despondent to realize he was completely dependent on UNHCR and the Bangladeshi government.

"When I was outside I had freedom of movement," says Uddin, now 36. "Camp is restrictive. Camp is high density. This is a hard life. I did not find any advantage in camp life."

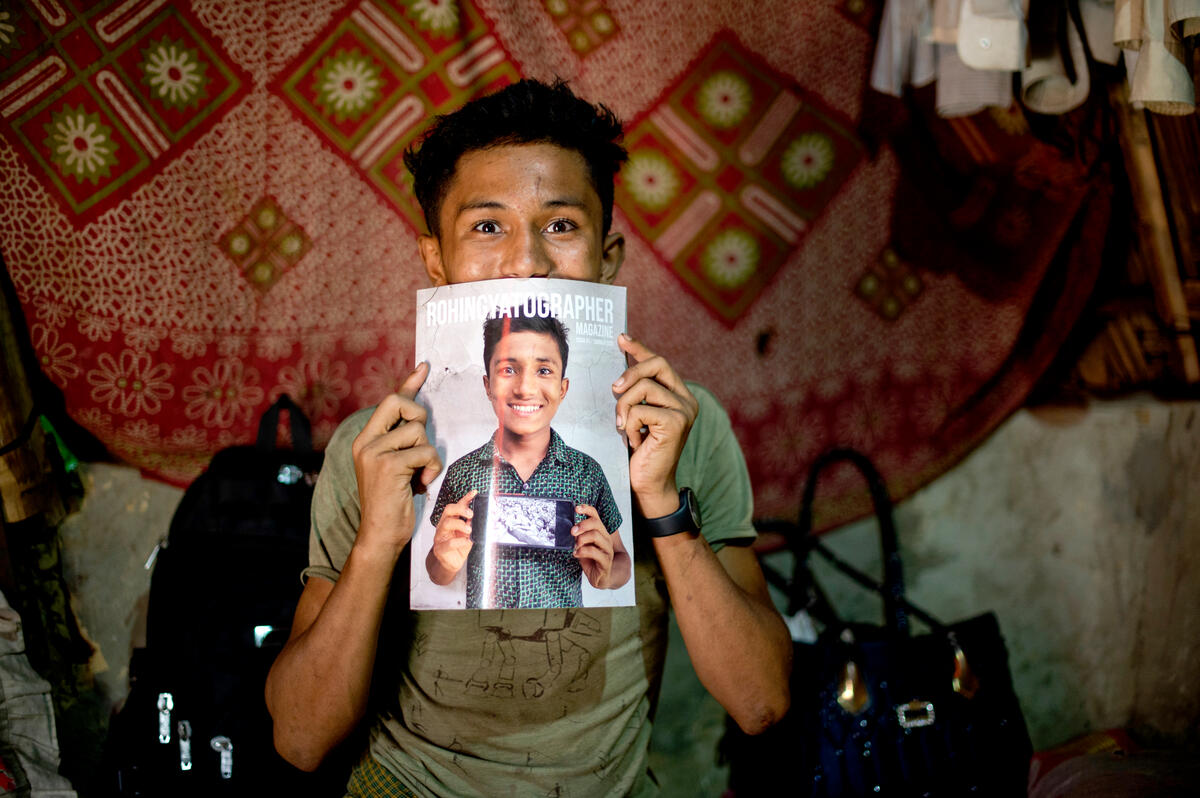

To his surprise, though, he prospered in Kutupalong Refugee Camp, home to 10,950 of the Rohingya refugees, Muslims from northern Rakhine state, who fled Myanmar in large numbers in 1991. The majority of the 250,000 who crossed into Bangladesh have since returned home.

With training and education offered by the UN refugee agency and its non-governmental organization partners, Uddin says he found opportunities in the refugee camp were far greater than in Myanmar.

"It's the difference between the sun and the ground," the articulate young man says, gesturing with his hands. "I've received opportunities here for education, the right to speak, the right to move, the right to help the community, the right to knowledge."

Uddin was a teenage student at a madrassa (religious Islamic school) in Myanmar when his life begun to turn upside down. He says his family's land was confiscated and he was forced to do unpaid labour. Finally, he and his mother fled to Bangladesh to escape their harrowing life.

Once in Kutupalong in 1994, Uddin had no thought beyond surviving and never imagined that 14 years later he would still be there. He set up a small school to teach youngsters to recite the Koran, and steadily built a reputation as a fair and trustworthy man. He ran a madrassa of his own, became an imam in one of the mosques in the camp, married a fellow refugee and had five children.

After the majis - appointed refugee leaders who exploited and terrorized the refugees - were removed from power last year, a more democratic camp management committee was put in place. To his astonishment, Uddin was elected - practically by acclamation - by his fellow refugees to head the 18-member body. These days he spends his time representing the refugees' interests and adjudicating disputes between refugees.

"With the assistance of UNHCR we have learned about humanity and the responsibilities of the person to the community and how to behave towards people," says Uddin, dressed in the long robe and skull cap of a religious Muslim.

"We have a taste of everything, but being in a refugee camp we are not able to enjoy it thoroughly."

He ponders the limits on his future - "we are not citizens of our own country; Bangladesh is overpopulated and Bangladesh does not have any space" - and hopes for something better for his children.

Still, he dreams of one day going back to the place he still calls "my country." But he prefers to envision it as a peaceful, democratic country, one that extends full citizenship and related freedoms to all Rohingya. "This is my native country," Uddin says. "Someone could give me the whole world, but it doesn't compare to my village."

The plight of the refugees in Bangladesh will be among the major protracted refugee situations discussed in Geneva on Wednesday and Thursday under the annual High Commissioner's Dialogue on Protection Challenges. Some 300 representatives of more than 50 governments and governmental and non-governmental organizations are expected to attend the meeting in Geneva's Palais des Nations and seek solutions for millions of people.

By Kitty McKinsey in Kutupalong Refugee Camp, Bangladesh