Stateless in Dushanbe: a woman struggles to win back her citizenship

Stateless in Dushanbe: a woman struggles to win back her citizenship

DUSHANBE, Tajikistan, December 11 (UNHCR) - Mukhabbat* carries around a thick wad of documents she has gathered over the last two years in a tireless effort to regain a nationality. "I can't remember how much it has cost, but I have spent a lot of time collecting these documents," said Mukhabbat, who recently approached UNHCR's office in Tajikistan to ask for help in finding a solution.

The problem that the 50-year-old faces, and tens of thousands of others left in legal limbo in Central Asia after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, has been debated at a regional conference on statelessness this week in the Turkmenistan capital, Ashgabat.

The European Union-funded conference, organized by UNHCR and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, followed a series of national workshops in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan and seeks to galvanize a collective response to address gaps in laws and procedures.

Mukhabbat was born in northern Tajikistan's Sughd province in 1959, when the area was known as Leninabad and formed part of the Soviet Union. Her troubles began a year after independence in 1991, when she fled to neighbouring Uzbekistan after the 1992-1997 civil war erupted in Tajikistan.

She lived for 17 years in Uzbekistan, drifting in and out of an unhappy and childless marriage to an Uzbek citizen that finally ended in 2007. She decided to go back home and was shocked to discover that she had lost her Tajik citizenship and was stateless. Today, she lives at a friend's house in Dushanbe, collecting other people's cast-offs and rubbish to help her survive.

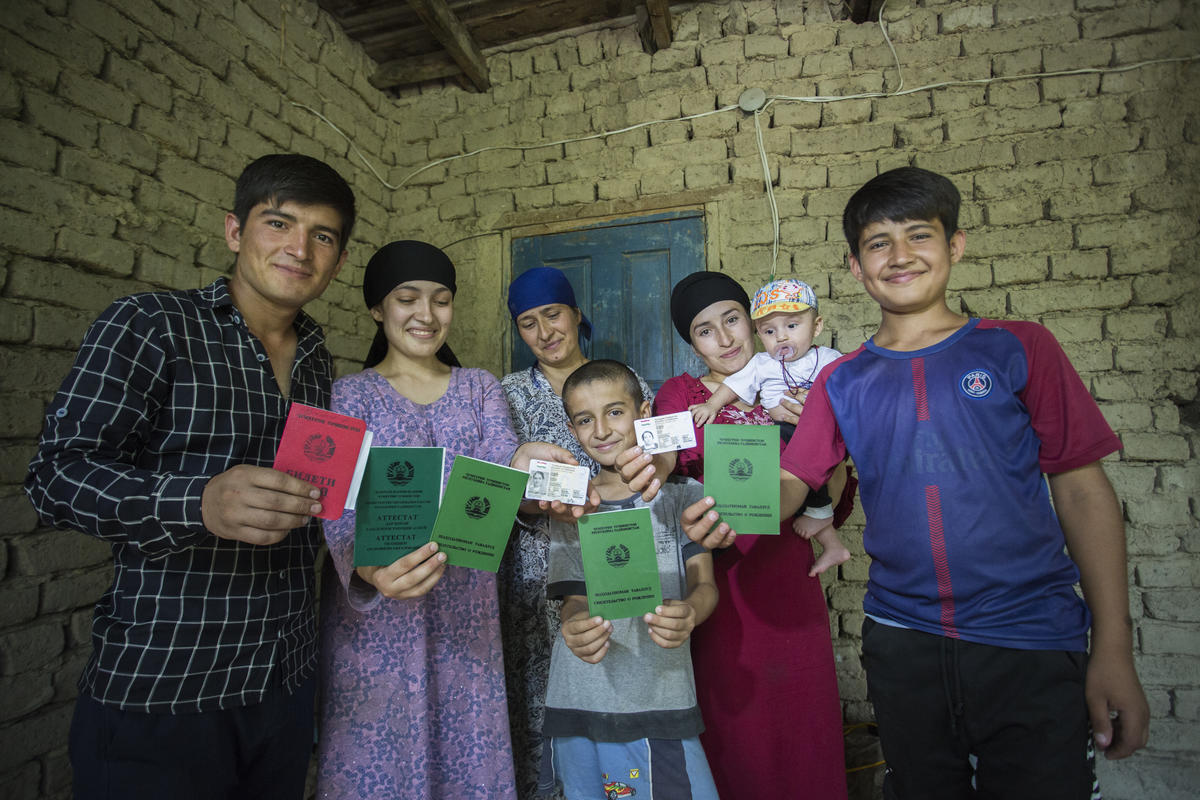

Mukhabbat had become a statistic - one of an estimated 12 million stateless people around the world, including 40,000 documented stateless people in the former Soviet Central Asian republics. These people do not possess a nationality nor enjoy its legal benefits. This often leaves them unable to do the basic things most people take for granted, such as registering a birth, travelling, going to school, accessing health care, opening a bank account or owning property.

Among her pile of documents, Mukhabbat has a photocopy of her former Soviet passport dated 1983. She also has an expired certificate of statelessness from Uzbekistan, which was issued after her marriage in 1995 and shows her earlier attempts to acquire a valid identity document. She also shows a UNHCR visitor old school records from the state archives, which she hopes will bolster her case.

But she still lacks two crucial documents: written confirmation that she is not a citizen of Uzbekistan and a certificate showing that Uzbekistan was her last place of registered residence. Getting the written confirmation, or spravka, can take years and cost a lot of money

Asked how she ended up without a nationality, Mukhabbat said she knew that she needed to secure a new document to replace her Soviet passport, but the complexity of the process and her personal situation at the time made it difficult.

"I understood that when there was no more Soviet Union, I would need to get some kind of document. But when I left for Uzbekistan, there was no Tajik passport yet," she said, adding: "In Uzbekistan, I didn't really know what a passport was, what a residence permit was, what a stateless certificate was . . . there are just too many documents and it was difficult to understand."

Mukhabbat said that in 1995 or 1996, she heard that "there was some talk that people like me from Tajikistan might get Uzbek passports. But I wasn't able to get one because I was moving around at this stage; my husband kicked me out and I was living on trains, sleeping in railway stations and in cotton fields."

Ever since returning to Tajikistan, she has been shuttling between Uzbekistan and the land of her birth in search of a nationality. "I even went to the Russian Embassy in Uzbekistan to ask for citizenship. I received a long list of documents and spravkas to submit, and I needed to pay money which I didn't have," she explained.

Without any nationality, she cannot get free medical help for her back problems. Nor can she live in the Dushanbe apartment that was issued to her by the textile factory where she worked as a young woman.

Two months ago, a frustrated Mukhabbat approached the UN office in Dushanbe for help and was referred to UNHCR, whose non-governmental organization partners are helping her to navigate the process, apply for documents and pay consular fees to the Uzbek Embassy for spravka applications.

Ghulam Shermamed, who works for UNHCR's legal aid partner, Society and Law, said Mukhabbat recently had an interview at the Uzbek Embassy and expects to receive her paperwork in about a month. Shermamed, a lawyer, said Mukhabbat checks on her application twice a week while he calls the embassy every day to check on the application for documents. "It is important that these people see that we are serious about it," he said.

Meanwhile, Mukhabbat faces the daily risk of being stopped and questioned by the authorities in her own homeland. "She can be stopped at any time for a document check, but she has none," said Shermamed, "She is not registered anywhere and staying without a document is considered a crime," he noted.

* Name changed for protection reasons

By Ariane Rummery in Dushanbe, Tajikistan