Revolutionary housing project brings Dutch youth together with refugees

Revolutionary housing project brings Dutch youth together with refugees

Adrian Laidley grew up fearing for his life. As a gay man in Jamaica, he had to hide his sexuality to protect himself against violent attacks. Now a refugee in the Netherlands, he has found safety and personal freedom as part of a revolutionary housing project for refugees and Dutch youth.

“I was afraid to be beaten - even to death, so I had to hide,” said Adrian, 23, who fled his home in the Jamaican capital of Kingston in 2015. “Every day I felt less safe in my community.”

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people routinely face violence, discrimination, and even criminal penalties in Jamaica. Terrified of being cast out by his family, Adrian concealed his sexual orientation for as long as he could. But he couldn’t hide forever.

“If you come from a community where being gay isn’t accepted at some point you have to leave, and you usually end up on the street,” said Adrian. “I feared that. It was approaching that point for me.”

Adrian secretly sought support from an NGO working with LGBTI youth and signed up for a program helping those in danger to flee the country. Early in 2015, Adrian joined a waiting list of people hoping to find safety in Europe.

“I made this decision entirely on my own to leave, I couldn’t speak to anyone about it,” said Adrian. “I was really anxious, ready to go any time. I was on edge, I couldn’t make plans for the future.”

While he waited for his turn to leave, Adrian prepared for his new life, studying Dutch and learning about the Netherlands’ history and culture. He knew it would be colder, that the food and the beaches would be different. And he had a vague idea he would be free to live and love as he wished.

“I knew I’d get to start my own life, to choose my own way,” said Adrian. “But I didn’t know what that would mean. It was a whole new experience for me.”

At last, the call came. With just five days to prepare, Adrian told family and friends he’d won a scholarship to study in the Netherlands. Within days, Adrian was sitting opposite immigration officials in Amsterdam airport. When he told them why he was there, they replied he didn’t have to worry anymore, that he could be himself.

“They told me: it’s ok, you’re finally here,” he said. “You can be who you are. I felt free and I knew I didn’t have to hide anymore, I didn’t have to continue being persecuted.”

"If I had still been in Jamaica, I’d probably be dead."

Just weeks later, an acquaintance outed Adrian to his family and friends back in Jamaica. His two brothers and most of his friends disowned him, while his mother and sister warned him never to return home.

“I felt totally rejected,” said Adrian. “I had no friends, no network here. It was overwhelming being in this big empty place without anybody. But I was lucky I was already here. If I had still been in Jamaica, I’d probably be dead.”

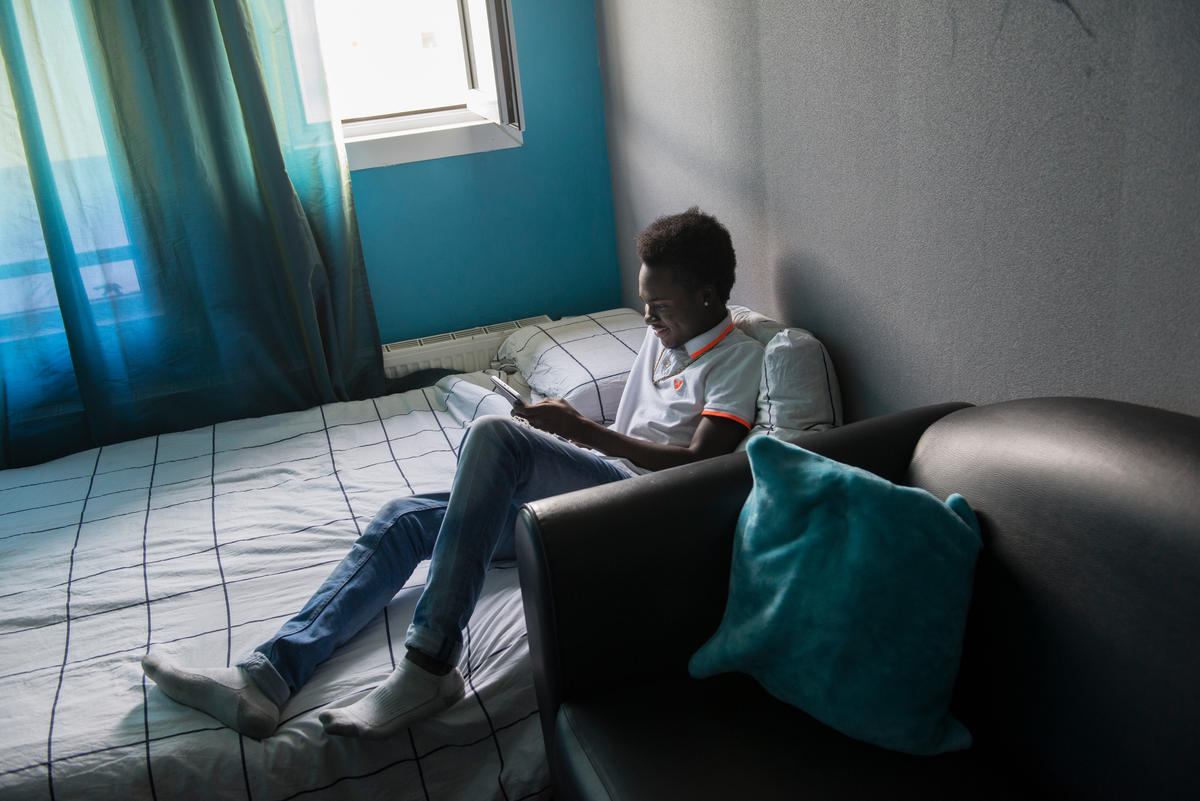

Adrian was granted asylum and moved from asylum-seeker accommodation into a shared flat in Amsterdam. Then came a stroke of luck: he was given a studio apartment at Startblok, a new municipality-run housing project in the city’s outskirts.

The idea was radical: Nine blocks of shipping containers stacked on a former sports ground were transformed into affordable housing for 565 residents; half of them refugees, the other half young people from the Netherlands.

Adrian moved in when the project launched in summer 2016. His new apartment was on a corridor with 26 others – an equal number of locals and refugees from countries such as Syria and Afghanistan. Suddenly, Adrian found he was no longer isolated.

“Before I was only sharing with other refugees - I didn’t meet my neighbours.”

“Before I was only sharing with other refugees - I didn’t meet my neighbours,” said Adrian. “It was a big difference living here, where everyone becomes your friend.”

Taking advantage of regular events, classes and meetups held in Startblok’s clubhouse, Adrian soon built a group of friends from all over the world.

“Adrian and I realised straight away we had the same wicked sense of humour,” said Dutch resident Amber Borra, who moved into a shared apartment at Startblok to escape overcrowded student accommodation. She was amazed to find such an easy-going atmosphere.

“You meet people so easily here,” said Amber, 26. “I was interested to live with newcomers because of all the things you hear in the news. I felt that people weren’t getting a fair hearing, so I had to experience it for myself.”

In the eighteen months since they first met, Amber has helped Adrian learn Dutch and adjust to his new life in the Netherlands. But for Adrian, living at Startblok is about more than integrating, finding friends and building a network. It’s his chance at last to live openly, free of fear.

“I learned that people here in the Netherlands are open and they expect openness of you,” said Adrian. “That was great to hear. Everyone is open-minded and friendly. We understand each other and the different reasons why people are here.”

Adrian is now studying and working part-time for Startblok, giving tours to interested visitors from all over the world. He has no plans to move.

“I don’t want to lose all the friends I have here,” said Adrian, who in a few years plans to apply for Dutch citizenship. “I’m used to this life now, seeing refugees and Dutch people every day and they’re just normal people. It’s a relief to be here. I try to make the best of it.”