UNHCR concerned about children in mixed migration flows through Mexico

UNHCR concerned about children in mixed migration flows through Mexico

MEXICO CITY, Mexico, November 12 (UNHCR) - As more and more people use Mexico as a stepping stone to try and reach North America, the UN refugee agency and its partners have increased their monitoring of this migration flow in a bid to detect people in need of international protection - especially children.

Unaccompanied minors will be among the topics to be discussed on Thursday and Friday next week in Costa Rica at a regional conference on refugee protection and migration. UNHCR is spending growing resources and time on this issue.

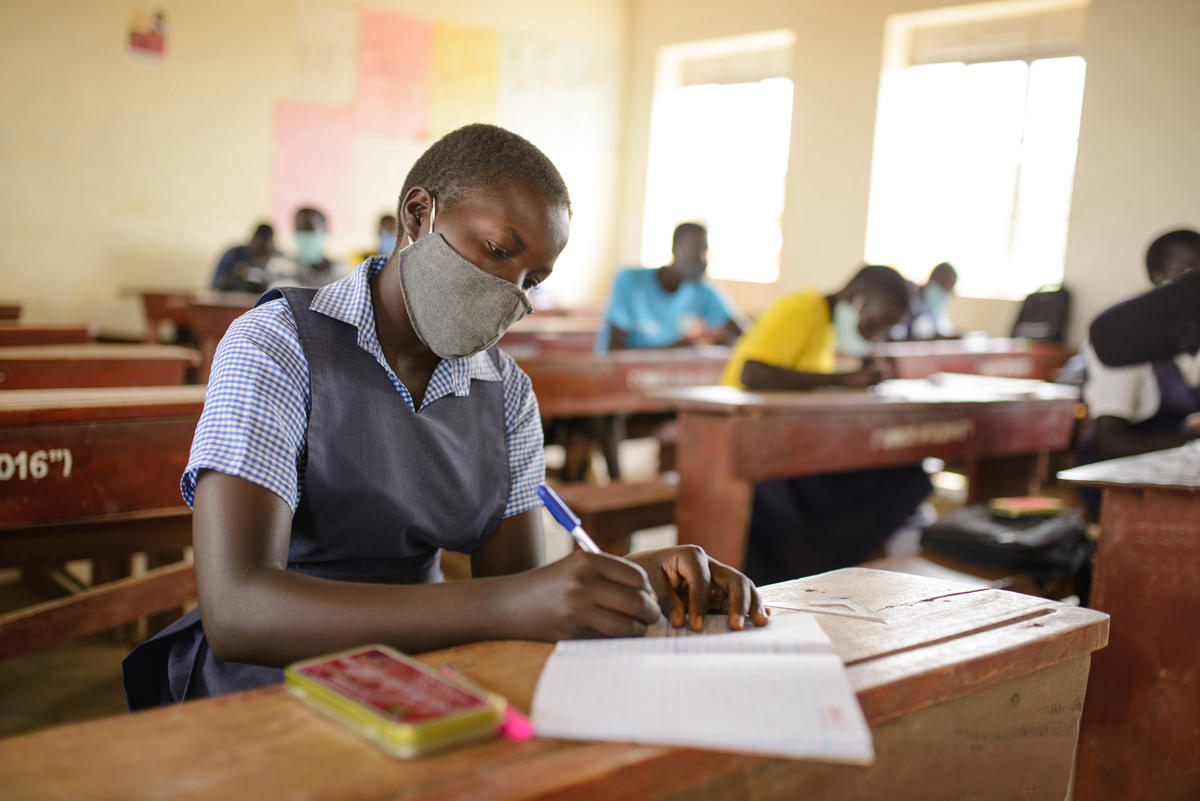

Children account for 8 percent of all undocumented migrants intercepted by the immigration authorities in Mexico, the bulk of them in the south. While most are trying to reunite with their families in the United States or Canada, some have fled persecution or conflict, which means they are people of concern to UNHCR.

In the last three years, Mexico's Migration Institute has appointed 170 child protection officers, like Grecia Campos, to ensure the rights of unaccompanied minors caught in the south-north mixed migration flows. The officials have been trained to detect and respond to the most urgent needs of detained children, and to facilitate the lodging of asylum claims.

"It's been an amazing experience to assist these children," said Campos, who works out of Villahermosa, capital of the southern state of Tabasco, one of the irregular migration hot spots. The former policewoman holds a degree in sociology and specializes in protection of children who seek or need asylum.

It's an important job, as Fernando Protti-Alvarado, UNHCR's representative in Mexico, indicated. "We have noticed that, many times, potential asylum-seekers are unaware of their right to apply for refugee status or are ignorant of the existing mechanisms to do so."

That's especially true about the children among the half-a-million or so people who pass through Mexico, or try to pass through, on irregular migration routes every year. In the first nine months of the year, more than 56,000 undocumented migrants were detained by the Mexican authorities.

"Most of the cases that arrive here are boys aged from 15 to 17, but we have also had cases of girls as young as 13. There was once a 14-year-old girl who was carrying her eight-month-old baby," explained Child Protection Officer Campos. "Around 70 percent of the minors we have here are Hondurans, and the rest are from Guatemala and El Salvador," she added.

UNHCR, meanwhile, has a permanent programme to train immigration officials and child protection officers on how to help unaccompanied refugee children, or those in need of asylum and protection.

"When I took the training course, I thought I was never going to have a refugee case, but I soon ended up with a Guatemalan kid who had been shot and persecuted by gang members after he refused to join them," Campos said. "He was eventually granted refugee status, but in the beginning . . . he didn't want to talk to me. So I had to be patient and wait until he had grown to trust me."

The child protection officers also ask all the unaccompanied children they interview to fill in a questionnaire about what risks they could face if sent back home, including domestic violence, persecution and kidnapping. They are also asked to list abuses they have faced during their journey.

"The stories that you hear are heartbreaking," Campos said. "You can't imagine the situations some of these children have had to deal with."

Aside from Tabasco, UNHCR also monitors the mixed migration flows in the southern Mexican states of Chiapas, Quintana Roo and Oaxaca, from where almost 60 percent of the total asylum applications in Mexico this year have come.

Currently Mexico hosts around 1,200 refugees. Most of the recent arrivals have come from Colombia and Haiti, while a few have originated from Africa and Asia, especially the Middle East.

By Mariana Echandi in Mexico City, Mexico