Refugee children find voice in Romania's inclusive choirs

Lina Jammal knew her son Sam was musical. When he was a small boy, he would jump up on the sofa and sing along with the celebrities on the radio or television, using a hairbrush as a microphone.

Now Sam and his sister Sara have joined a choir as part of a Romanian programme to integrate children from different backgrounds, including refugees, through singing.

“As a mother,” says Lina, 39. “I am very happy to see my children fulfilling their dreams.”

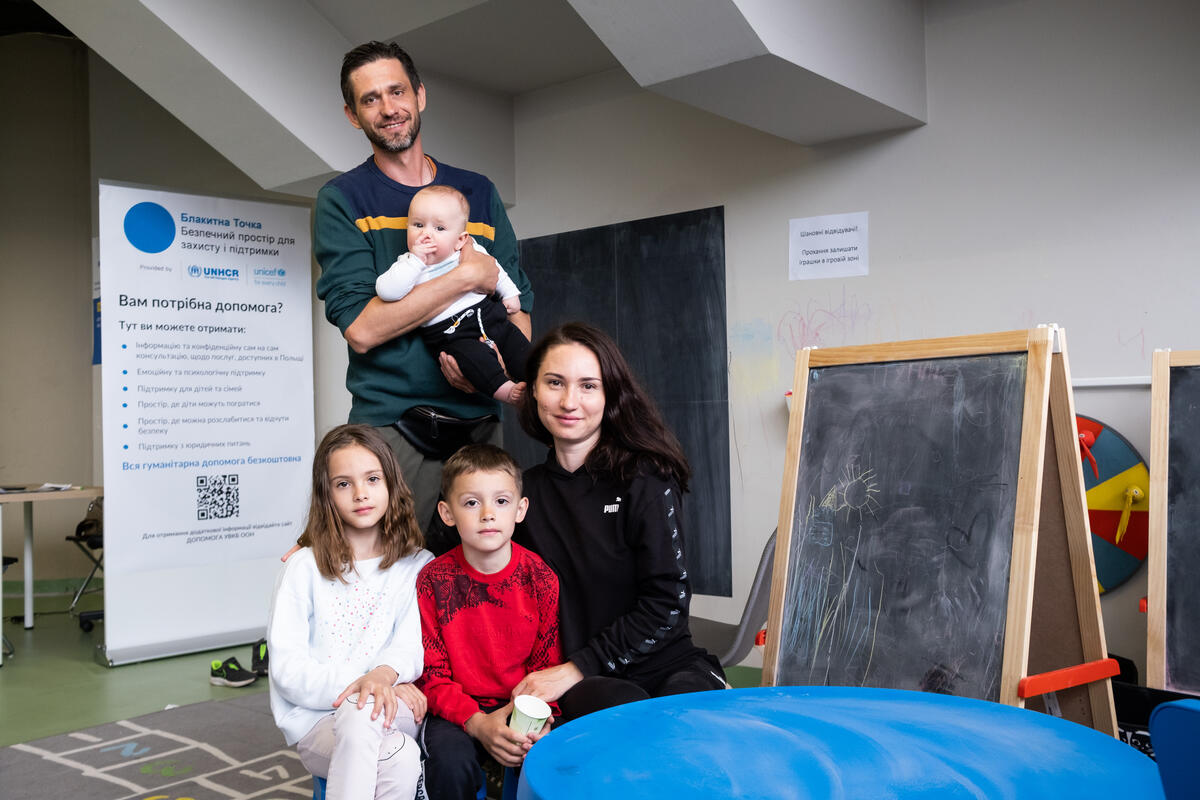

The Syrian family came from war-torn Aleppo to Bucharest in 2013. They travelled via Turkey to join relatives already in Romania. Three generations of the nine-member family live in a three-room flat on the edge of the city.

Lina’s husband Jihad, 46, has a job selling textiles. Her elder daughter, Budur, 22, and son, Abdul, 20, are at university, studying medical and civil engineering respectively. Grandparents sit quietly in the background while three-year-old Kaisar, born in Romania, runs around the living room.

“I am very happy to see my children fulfilling their dreams.”

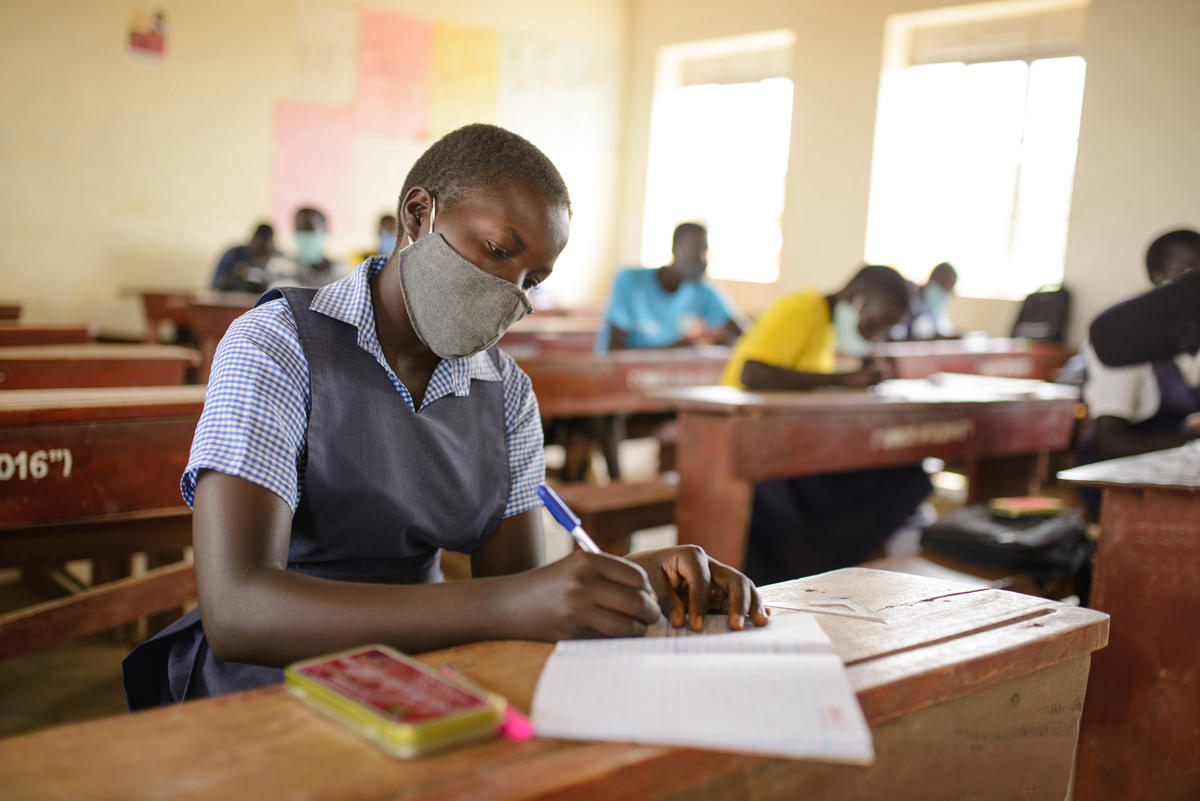

Sam, 12, and Sara, 10, attend an Arabic day school but attend choir practice twice a week at Bucharest’s Scoala Gimnaziala Ferdinand I (King Ferdinand High School).

The school, built in 1926, is taking part in a nationwide programme called Cantus Mundi aimed at bringing children together in choirs, The Cantus Mundi programme is an initiative of Romania’s renowned Madrigal Chamber Choir.

Some 30,000 Romanian children in nearly 850 different choirs – school ensembles, church groups, choirs for the blind and handicapped – are singing under the Cantus Mundi umbrella.

Only a few refugees are involved so far but the organizers want to include more. They see singing as one of the best ways to integrate refugees, as the newcomers learn the language and culture and interact with residents.

“The kids come from many different backgrounds,” says Anna Ungureanu, chief conductor of the Madrigal choir and artistic director of Cantus Mundi. “Children sing without any thought that ‘I am different’ or ‘I am better or worse’. Children don’t think like that. They feel the vibe.”

Back at the flat, Sam and Sara are getting ready to go to choir practice. Sam is dressed smartly in a grey suit while his sister Sara is pretty in a white lace blouse.

Sara is shy and does not like singing solo, so the choir is ideal for her. Sam has more confidence. He leaps up on the sofa to show how he used to sing with the hairbrush and raps out his own song about the war in Syria:

“When we go to school,

Say ‘goodbye’ to mother,

If we come back home,

Will we see each other?

Miss the crowded streets,

Syrian bazaars,

Remember sound of bombs,

Like bullets in my body.

When I watch TV,

Rather see the weather,

Don’t wanna see friends dying,

Don’t wanna see them hurt.

We are Syrians,

Gonna build Syria again,

We are Syrians,

Gotta to forget our pain.”

"I see this as a way to help them.”

The assembly hall at King Ferdinand School is filling up, as choristers arrive for the rehearsal. Sam and Sara join Romanian children their own age on the rows of chairs. Lina sits at the back and proudly watches them taking part.

Primary teacher and choir coordinator Simona Spirescu is committed to including refugee children in her classes. “I have an open mind and heart,” she says. “I read a lot about the refugees. I suffered and cried when I heard about them. I see this as a way to help them.”

She is joined on the platform by Emanuel Pecingina, a tenor from the Madrigal choir, who is both teaching her how to conduct and giving singing lessons to the children.

Pecingina speaks of Romania’s rich choral culture, rooted in Byzantine and folk traditions. Under communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu, Romania had mass choirs.

“We sang patriotic and party songs,” he recalls, “not bad music but bad words. The repertoire is different now, of course.”

This is why, after warming up the children’s voices with “ma-me-mi-mo-mu,” he draws staves on the blackboard and drums in the basics of the tonic sol-fa.

Then the children sing “Frère Jacques” in several languages and a song about a watering can. The songs are simple, but the sound is bright.

“Bravo!” shouts Pecingina and the rehearsal ends with another Romanian favourite, “Vine, Vine Primavera!” (“Spring is on the way!”).

He outlines the benefits of the programme: “We are creating normality by including all children. It’s a cultural exchange. The refugees will also bring songs from their countries. Music is universal.”

Sam and Sara seem happy. “When I sing on my own, I don’t hear my mistakes. In the choir, I listen, repeat and get better,” says Sam.

When it comes to the choice of songs, perhaps Sam has doubts about “Frère Jacques”.

“It’s good to be in the choir,” he says, “but rapping is still better.”