Giving up your child to save her: a tale from Tunisia

Giving up your child to save her: a tale from Tunisia

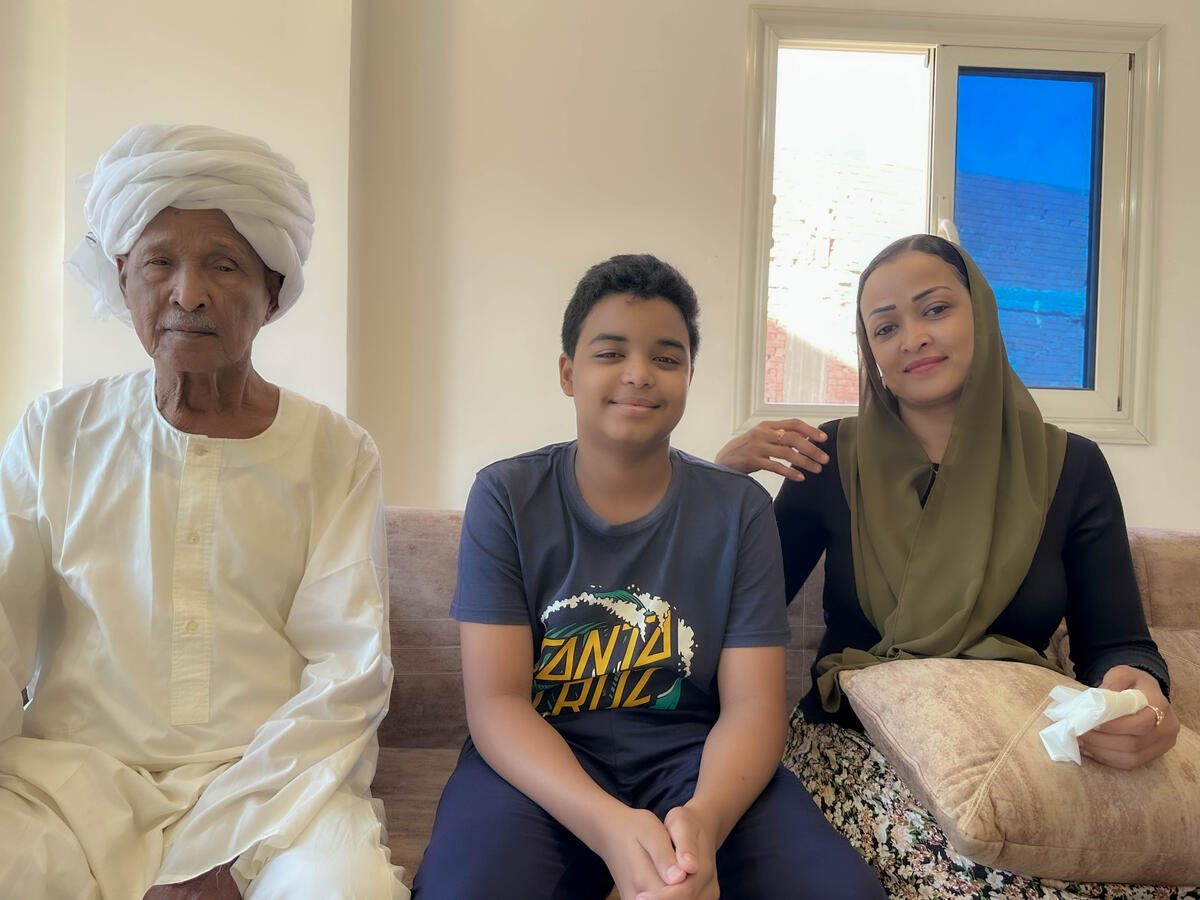

CHOUCHA CAMP, Tunisia, March 16 (UNHCR) - With smooth features and a calm way about him, Abdullah Omar, 25, comes across as someone accustomed to hard choices. But the decision to send his one-year-old daughter back to war-ravaged Somalia, because he could not afford to support her, was one of the hardest he and his wife Khadija have ever faced.

That was five months ago. "There is not a night that goes by when I don't lie awake thinking about my baby and worrying about her," Khadija told me here at the windswept Choucha transit camp just inside Tunisia.

For the young Somali couple it was the most challenging in a series of ordeals that they have endured in the four years since they fled Somalia - from a 10-day truck journey with people smugglers across the Sahara to serving time in detention and being hounded by racist thugs in Tripoli.

Now the pair have washed up in Choucha, along with hundreds of other Somalis who have fled the violence and conflict in neighbouring Libya.

"I am fearing for my family. I am fearing for my daughter. Really I am!," Omar told me on a stormy morning last week from the green canvas tent he and his wife now share with another family. "I am fearing that if I go back to [the Somali capital] Mogadishu I will be killed."

Refugees from Somalia, Eritrea and Côte d'Ivoire are a minority among the more than 200,000 people to have fled the violence in Libya in recent weeks.

But unlike migrant workers from more peaceful countries like Bangladesh, who came to Libya only temporarily and are now headed home, they face an uncertain future.

Some may be resettled. Others will have the option of staying in camps in some other country. "I really don't know what I will do," Omar says.

His and Khadija's journey began four years ago in Mogadishu, when fighting between the Ethiopian-backed transitional federal government forces and Islamic Courts Union fighters forced them from the city. His sister was caught in the crossfire and killed; his wife was slightly wounded.

Since he is the eldest in his family, his mother told him that he must go abroad to help find a way out for the whole family. He and Khadija travelled first to Khartoum, capital of Sudan, where they arranged with people smugglers for passage to Libya. The 10-day journey in the back of an exposed Mercedes truck ended with their arrest at the Libyan border.

Omar was held in prison in the middle of the Sahara for five months. One day he and six cellmates (Khadija had been moved to a prison in the port city of Benghazi) decided to break out. "We thought: it is better to die trying to escape than go on living in this way," Omar explained.

They overpowered the guard and ran from the compound. Forty prisoners broke out on that day; 20, including Omar, got away. Escaping to the north, the Somali arranged to collect US$800 from his wife's uncle in Texas to pay for her release.

In Tripoli, Khadija worked as a cleaner. But then she fell ill. And Omar says he could not find a job. Many sub-Saharan Africans in Tripoli are only permitted to do menial work.

After their first child, Rayan, was born, "my wife was ill . . . I wanted my daughter to stay with us so much. But I could not afford even her milk. That is why I decided to send her away. To this day I am not happy without her." Khadija rummages in a dark corner of the tent and fishes out a photo of her baby taken the last time they saw each other. The child returned to Mogadishu with relatives and now lives with her grandmother.

The latest violence started with the announcement on state TV three weeks ago that sub-Saharan Africans were fighting Libyans and "killing them in their homes," Omar says. He and his wife knew what this meant: they would be targeted.

They barricaded themselves inside their apartment for two weeks, too afraid to go out even for food. Roadblocks festooned with green flags sprang up around their neighbourhood. "Libyan youths stopped you and kept asking questions you could not answer," Omar says. Finally, one week ago, the couple made a dash for the border, paying US$200 to a Libyan driver.

Today, he worries about friends and thousands of other Somalis still inside Libya. He is on his mobile phone every day. He says he is hearing reports that the escape routes are now unsafe. Rumours reach the camp of Somali women being raped. "I am very very worried for the Somalis there," he admits.

To help people like Omar and his family, UNHCR is organizing the camps on the border, offering counselling on solutions for such families, which may entail resettlement to a third country or, if that is not possible, support in a camp or an urban community in another country and urging safe passage for all civilians from the conflict zone.