Growing numbers of unaccompanied minors seek asylum in Belgium

Growing numbers of unaccompanied minors seek asylum in Belgium

STEENOKKERZEEL, Belgium, May 2 (UNHCR) - The UN refugee agency and the Belgian government are increasingly alarmed at the rising number of unaccompanied children seeking asylum in the Western European country and at how young many of them are.

Preliminary government statistics indicate that the number of unaccompanied minors applying for asylum in each of the first three months of this year are much higher than for the corresponding period in 2010. In January this year, 138 children sought asylum against 59 in January 2010; the figure for February was 149 against 56 while in March a total of 196 applied for asylum against 47 a year earlier. At least one in five were girls.

''Not only do we notice that more underage children are arriving in Belgium, but they also are getting younger," noted Ingrid Reumers from Belgium's Federal Agency for the Reception of Asylum-Seekers (Fedasil). "Until 2009, the average age of these youngsters was 16-17 years old, but recently we are seeing more children who are as young as 12." Some are sent alone with smugglers, others get separated from their families during their long and often dangerous journey.

Government figures for the first two months of this year showed that almost 60 per cent of the children turning up on their own hailed from just two countries - Afghanistan (38 per cent) and Guinea (18.5 per cent). The other main countries of origin include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia, Rwanda and Iraq. It is a phenomenon faced by other European countries.

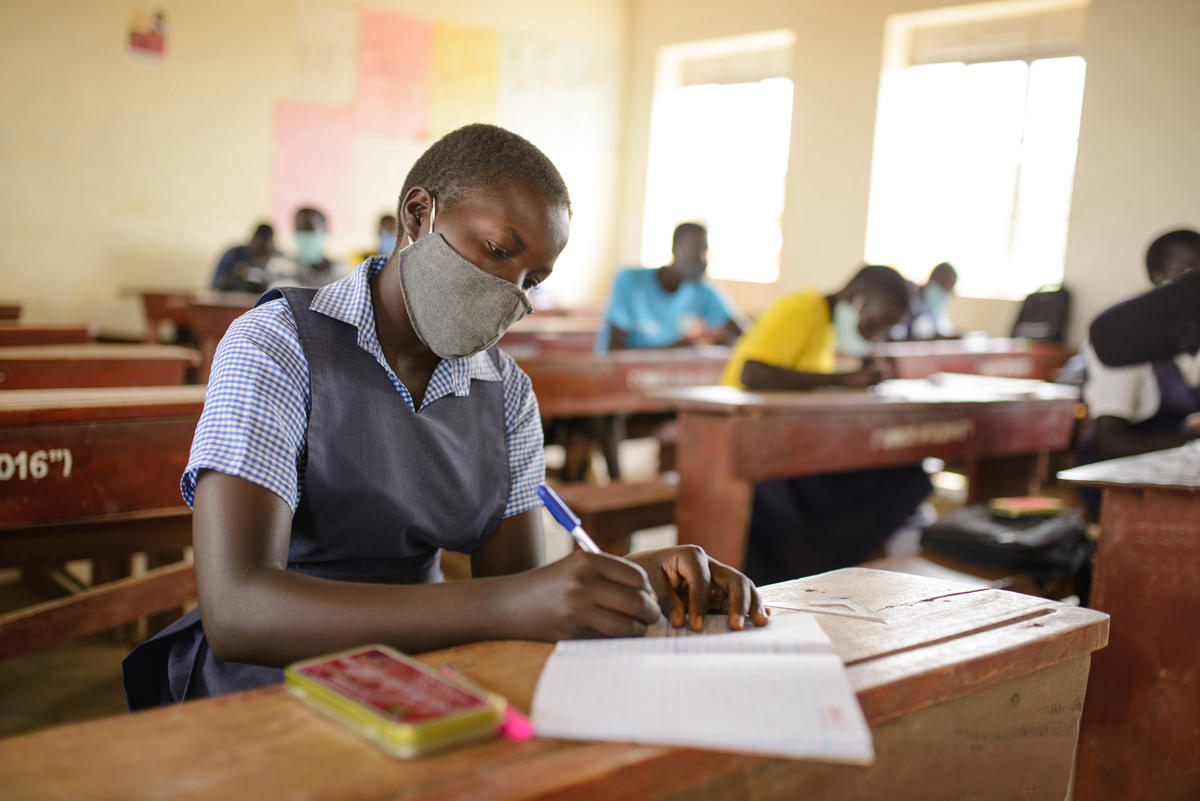

It's not clear why the figures have risen so much and the reasons why parents send their children away on their own are complex. For some Afghan families, sending one child ahead is like putting down an anchor in Europe. But others worry about the lack of education opportunities at home while many are genuinely scared for their children because of the fragile security situation in parts of Afghanistan and the risk of forced military recruitment.

In parts of East Africa, security is also a concern, while in some countries girls mention a fear of genital mutilation for leaving alone or of being forced into early marriages.

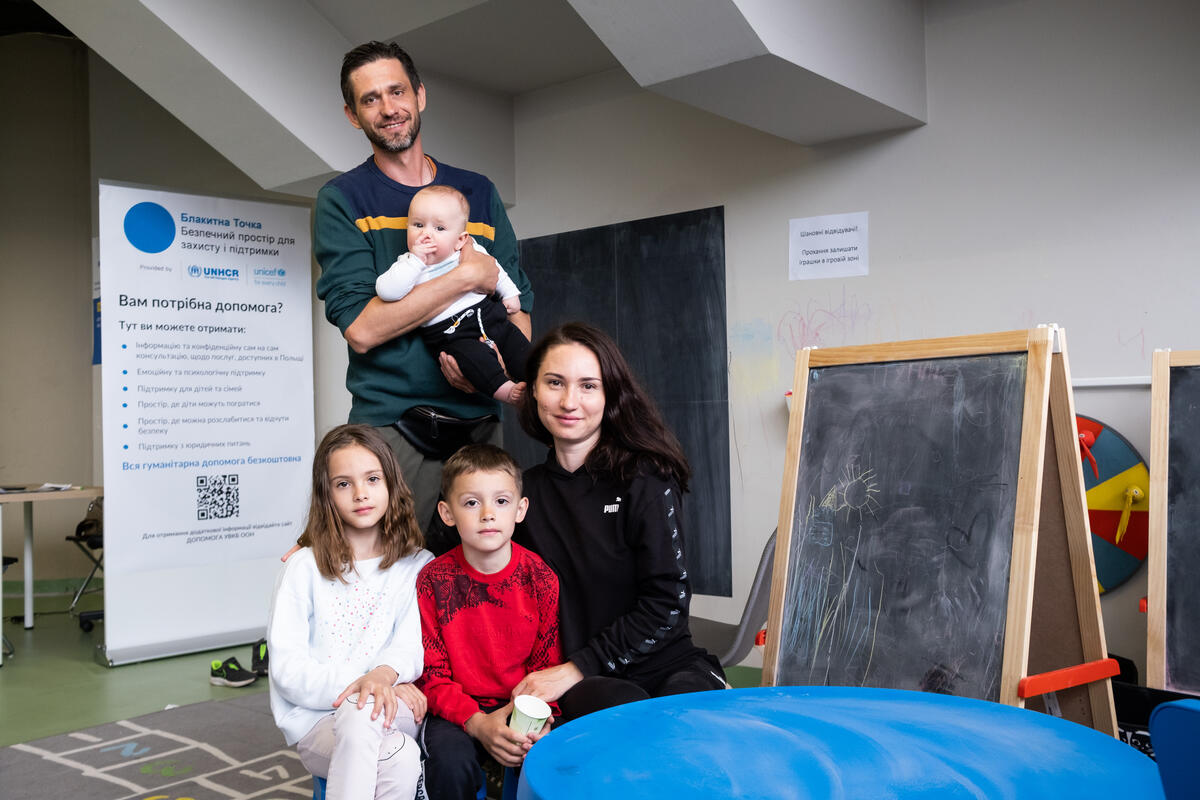

When unaccompanied children seek asylum in Belgium they spend a few weeks in one of two Fedasil observation and orientation centres. The centres in the northern Belgian municipality of Steenokkerzeel and at Neder-over-Heembeek provide food, shelter, trauma counselling, medical treatment and social and leisure activities as well as some basic schooling.

They spend two to four weeks in one of the centres, allowing staff to determine that they are minors and to draw up a first medical, psychological and social profile. They are then sent to collective reception centres, where they are kept in separate areas from adults and have their own team of educators and supervisors.

Many of the young people have harrowing tales. Blanche Tax, a senior policy officer for UNHCR, said that aside from abuse, hardship and danger on their journey to Europe, many unaccompanied minors were already suffering from traumatic experiences back home as well as poverty and lack of education. This made them all the more vulnerable.

About 50 unaccompanied minors were in the Steenokkerzeel centre when UNHCR visited, including 17-year-old Azlan,* who said it took almost one year to reach Belgium with the help of human smugglers. "I nearly got killed on the way," the teenager said, recalling a scary night passage through mountains.

"The smugglers beat us with sticks when we did not walk fast enough. But it was pitch dark and I slipped," he said, adding that he fortunately only fell a small way down the mountainside. Azlan now finds it hard to concentrate. "It is as if my perilous journey to Belgium has affected my brain," he said sadly.

A fellow Afghan, Mizral,* seemed listless and lost when asked about his situation. He shrugged his shoulders a lot and stared vacantly. He was initially placed in a hotel because the Fedasil's reception centres were full. Staff were trying to find out his true age and personal details.

Another child in the centre, 12-year-old Tahera,* was separated from her parents and four sisters in Greece. She wept when recounting the awful moment of separation, when she was too scared to board a smuggler's boat. The young Afghan has no idea what happened to her parents.

It is a terribly young age for a girl, let alone one from conservative Afghanistan, to be on her own without family or chaperones. Most of the Afghan unaccompanied minors are male. But Tahera was not the youngest child in the Steenokkerzeel centre. Staff said that dubious distinction belonged to an Angolan girl of only five-years-old, who arrived with her young brother.

Meanwhile, Azlan is already looking to the future. "I want to study and become a construction engineer. I do hope that Belgium can give me a form of security for the future.''

* Names changed for protection reasons

By Vanessa Saenen in Steenokkerzeel, Belgium