Refugees make protective masks to curb the spread of coronavirus

Refugees make protective masks to curb the spread of coronavirus

When 24-year-old Fardowsa Ibrahim signed up for a tailoring course, she didn’t imagine that six months later, she would be making face masks – much sought-after protection made necessary by the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The former refugee who returned to Baidoa in Somalia’s South West State from Kenya’s Dadaab camp four years ago, is among a group of returnees and internally displaced women, actively involved in helping curb the spread of the coronavirus by sewing face masks.

The women were trained by UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency and Mercy Corps and after the training, received startup capital and tailoring kits containing sewing machines, scissors, iron boxes, needles, thread and materials.

“I am proud to be contributing to the fight against COVID-19 by making these masks,” says Fardowsa, who’s married with four children.

Since April, the women have made over 3,700 masks and sold 2,000 pieces for 50 US cents to a dollar apiece, depending on the quantities purchased. Their customers include the State’s Ministry of Humanitarian and Disaster Management and other aid agencies.

“I am proud to be contributing to the fight against COVID-19 by making these masks.”

“I make up to 70 masks in a single day. I am so happy to see my family’s income increase day by day,” adds Fardowsa.

Four months into the COVID-19 pandemic, people across the world are adjusting to a ‘new normal’ that incorporates frequent handwashing with soap, observing social distancing and wearing face masks when in public. Refugees and displaced people have stepped up to help themselves and those around them by stitching face masks in various shapes, designs and colours.

In Kenya, after the first confirmed COVID-19 case in March, the government issued a directive requiring everyone to wear facemasks in public.

Maombi Samir, 24, from the Democratic Republic of Congo and a fashion designer living in Kenya’s Kakuma camp, realized that he could put his skills to a new use.

“There was a shortage of masks and I had seen samples of facemasks on the internet,” says Samir. “I wanted to use my talent to show that refugees can also contribute to the response.”

Using locally available fabric, Samir and his staff of three set to work and within a week, he had delivered 300 masks to the UNHCR office in Kakuma to be distributed to staff. He also gave away masks to refugees and locals who could not afford to buy them.

“We live in a community with many other refugees so the best we can do is to protect ourselves as much as we can,” he adds.

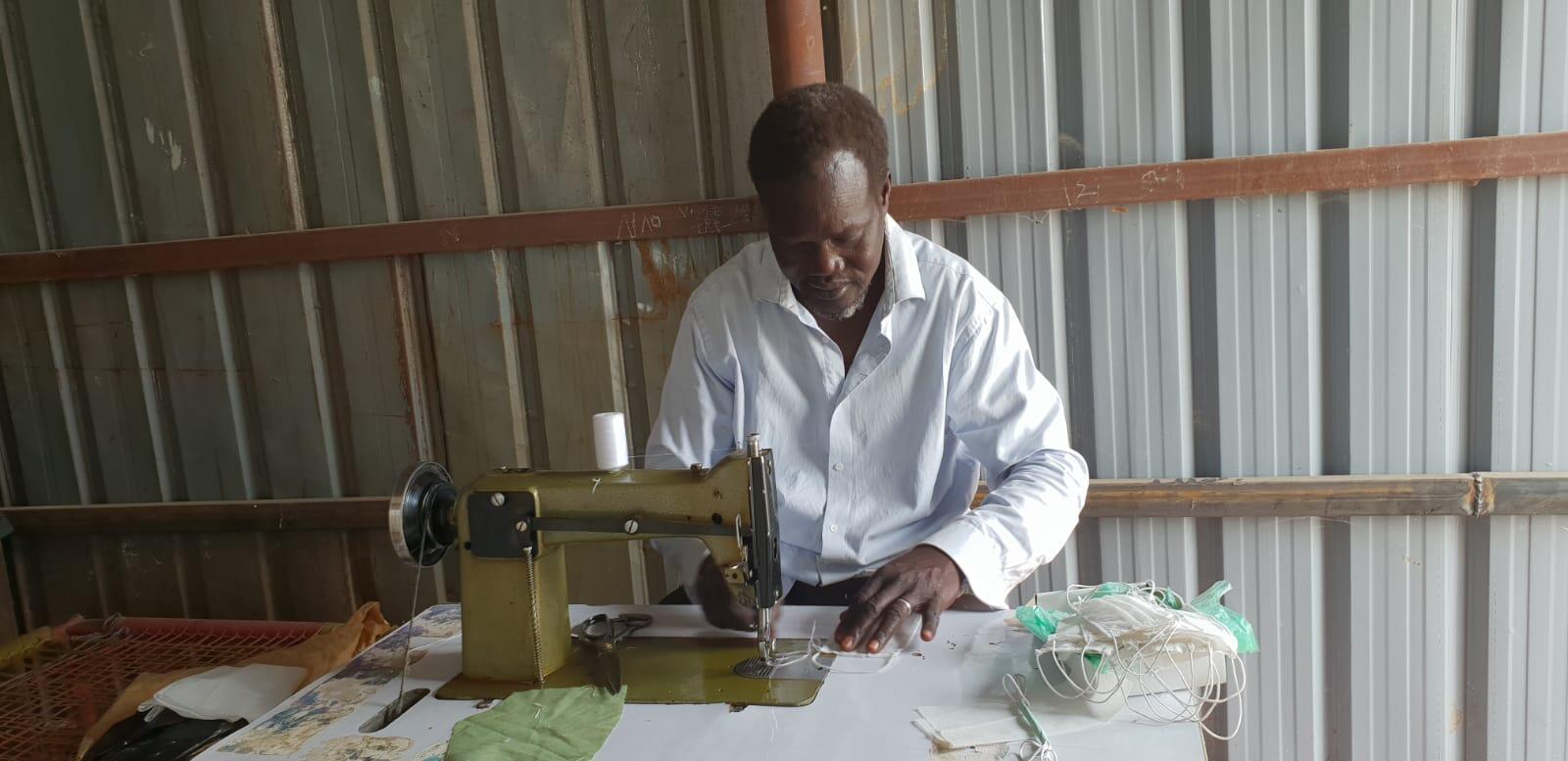

In South Sudan, internally displaced people (IDPs) at the UN site in Malakal stitch between 300 to 500 masks a day to support the COVID-19 response. Trained by UNHCR and the Humanitarian Development Consortium, a local non-profit, the tailors gather daily in a tent where they use pedal-powered sewing machines to make the masks.

Their workstations are spread out to comply with social distancing guidelines and their conversations are muffled by the masks they have on.

“All of us have a responsibility during this difficult time to confront this disease,” says Chan Ajak Deng, 43, who helped mobilize tailors to participate in the face mask project. “I believe we can all make a difference but only when we stand together as one.”

Chan taught himself how to sew prior to the civil war that broke out in 2013, so as to make his then new bride, Eliza, a beautiful dress.

It had taken him a month to finish the dress and soon, he was churning out enough garments to support his family of nine. After the war, he was forced to leave his tailoring business behind.

“All of us have a responsibility during this difficult time to confront this disease.”

When Eliza saw a UNHCR notice announcing the tailoring course, she told him about it and he jumped at the opportunity.

“My wife wanted me to continue making ‘the most beautiful dresses in South Sudan’ and I saw it as a chance to sharpen my skills,” he laughs.

Since production started, Chan and his fellow tailors have made over 6,500 masks. They are aiming for at least 8,000 masks by the end of June, to be distributed to health workers and vulnerable IDPs in Malakal and other displacement sites in remote areas.

Masks production is also under way in Wau, where UNHCR’s partner, Women’s Development Group comprised of refugees, IDPs and host community members, has produced 4,000 masks in three weeks, with an aim to produce a total of 12,000 masks.

In other parts of the continent where lockdowns have dramatically impacted refugees’ livelihoods, tailoring businesses are providing a lifeline.

Fatouma Mohamed, a Malian refugee living near Niamey, Niger’s capital, used to make and sell traditional Tuareg leather crafts. But after authorities imposed a lockdown, business dried up.

“Nowadays, people are scared to leave their houses. If I cannot sell my artifacts, I won’t have food to eat,” she says.

She started making face masks which she sells for about 50 US cents apiece to street vendors who in turn, sell them across the capital.

“I realize this is a temporary business, but with the money I make, I can continue to support my three children,”she explains.

Since April, refugees in Sudan’s White Nile State have made a total of 900 masks, to be distributed to fellow refugees and their host communities.

Trained by UNHCR and the Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA), the group of 11 refugees from Al Redis 2, Jouri and Khor Al Waral camps are working from a workshop normally used to make children’s school uniforms.

Their target is 9,000 masks and there are plans to involve refugees in three other camps – Um Sangour, Alagaya and Dabat Bosin.

In Tanzania, UNHCR has partnered with the Danish Refugee Council, HelpAge and MSF to engage refugees in camps in Kigoma district to produce face masks.

John Umimana, a self-taught Burundian refugee tailor, lives in Mtendeli camp and is the leader of a group of 1,200 tailors at one of the mask production centers.

“This project is a good opportunity for us to put our skills to good use in the fight against coronavirus,” he says. “I have trained many of these tailors how to sew and I am glad they can also participate in this effort.”

MSF is providing additional training so that each refugee receives at least two re-usable cloth masks.

Tanzania currently hosts approximately 286,000 refugees and asylum seekers, 86 per cent of whom live in three refugee camps situated in the Kigoma region.

In northern Mozambique, the German Development Agency, GIZ, through the Promove Agribiz Project, funded by the EU and the German Government, has provided masks produced by refugee tailors to Mozambicans employed in cashew nut processing factories. The refugees were trained by UNHCR, as part of its livelihoods programme.

“I like when we are producing masks because it brings us together.”

Bina Lom Lokole, a Congolese refugee and the leader of the tailors, explains how the project is beneficial.

“I like when we are producing masks because it brings us together,” he says. “Joining this project has given me courage and healed my heart because we are taking care of each other.”

The Nampula health district has ordered an additional 10,000 cloth masks to be made by refugees. These will be distributed for free to other refugees and host communities living in Maratane.

In Uganda, refugees are producing non-medical face masks for more than 217,000 refugees living in the 19 settlements in Adjumani and Palabek, in the north.

A total of 500 tailors from the refugee and local communities have been identified to produce the masks. Each tailor is expected to make at least 75 face masks a day and will work with adequate sanitation and monitoringfor compliance of standards.

Writing by Cathy Wachiaya with reporting by Njoki Mwangi for Somalia, Elizabeth Marie Stuart in South Sudan, Samuel Otieno in Kenya, Marlies Cardoen in Niger, Sylvia Nabanoba in Sudan, Winnie Italeli Kweka in Tanzania, Adaiana Lima in Mozambique and Duniya Aslam Khan in Uganda.