Despite COVID-19 school closures, refugees continue to study and sit for finals

Despite COVID-19 school closures, refugees continue to study and sit for finals

Jean Aimé Mozokombo has moved his classes outside. The Congolese teacher is among several dedicated teachers who have been keeping over 600 students busy since schools closed due to COVID-19.

For the past two months, he has conducted lessons outside his refugee students’ homes in Inke refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s North Ubangi province. He limits the lessons to six students at a time to ensure social distancing.

“We have distributed stationery to the students, though we lack basic school furniture like proper chairs and whiteboards, as the students don’t have such things,” he says.

Even without the usual school facilities, these outdoor classes are vital for the refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR), who are preparing for their final national primary exams.

“We are doing the best we can as the final test is essential for students to enrol in secondary school,” he adds.

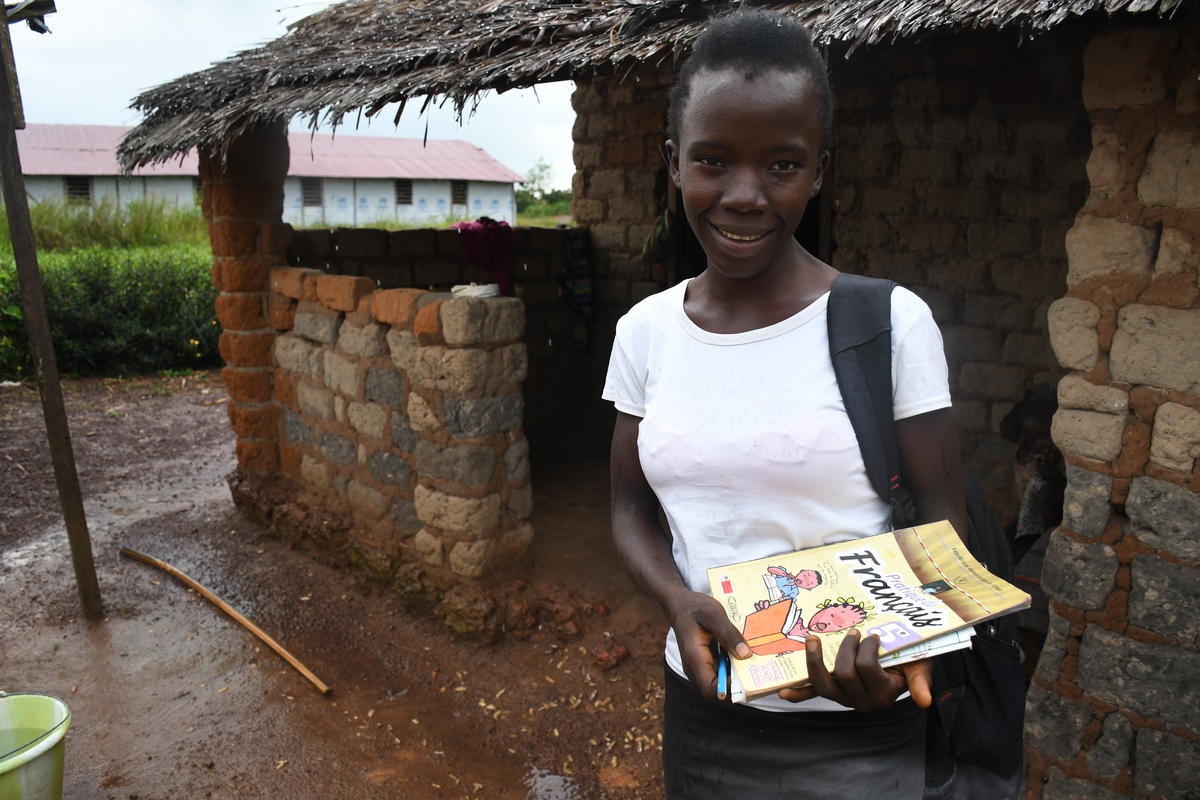

Angele, 15, is one of the students attending the outdoor classes.

“We are doing the best we can as the final test is essential for students to enrol in secondary school.”

“I feel confident about taking the test and lucky because not everyone has been able to continue learning during the pandemic,” she says. “It is important to study if we want to become someone in society, to serve our country and our family.”

Even with such concerted efforts, Central African refugees still struggle to access an education. Only about 8,200 of the almost 18,000 children in the camp have access to primary school and thousands of those students are forced to stop their studies at secondary level due to lack of available schools.

In a recent report titled “Coming Together for Refugee Education,” UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has found that while children in every country have struggled with the impact of COVID-19 on their education, refugee children have been particularly disadvantaged.

While 77 per cent of refugees globally are enrolled in primary school, only 31 per cent get into secondary school, with a dismal 3 per cent getting into institutions of higher learning.

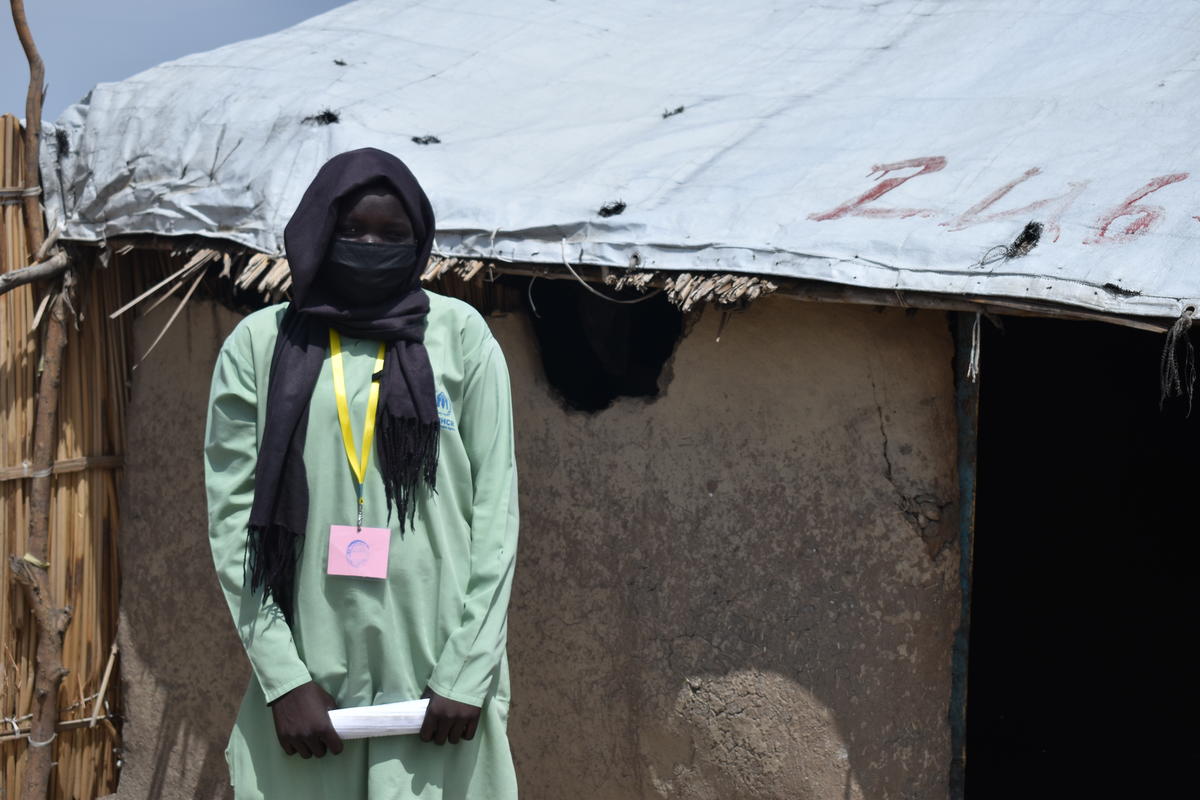

North of the DRC, thousands of refugees in Sudan have already sat for their finals. Fardoos Emmanuel is one of them.

Six months ago, Fardoos feared she would not sit her exams as the COVID-19 pandemic brought with it the immediate closure of all learning institutions in the country, including her school in White Nile State.

But today, the South Sudanese refugee’s spirits are high. Despite the school closures, she and nearly 2,000 Grade 8 students sat for their basic school leaving examinations in July.

“That exam was very important because it’s for our future,” said Fardoos who wants to be a doctor.

She was among thousands of refugees across Sudan whose prospects for graduating from primary school were nearly scuttled by the outbreak of the coronavirus in March. But by late June, the State Ministry of Education had announced the resumption of classes for students to prepare for the upcoming exams.

“My mother encouraged me to study during the lockdown period, so I stayed home and read my books,” she said.

Like Fardoos, Esteer Vinansio, from Al Redis 1 camp, also continued studying at home.

“We did not expect the exams this year so during the lockdown, my daughter revised on her own,” said Esteer’s mother. “Now that she has taken the exam, she can continue her studies and get a higher level of education.”

Adapting to the limitations imposed by COVID-19 has been especially tough for the 85 per cent of the world’s refugees who live in developing or least developed countries. Keeping education going has required resourcefulness, innovation, invention and collaboration.

The exams in White Nile State took place through the collaborative efforts of the State Ministries of Education and Health, UNHCR and several partners including UNICEF, Plan International, the Sudanese Red Crescent Society, Adventist Development & Relief Agency (ADRA) and the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD).

Together, they helped facilitate and ensure the safety of refugees taking exams across the state by providing protective equipment like face masks and handwashing facilities, as well as training staff on COVID-19 prevention.

As a result, thousands of refugees and internally displaced children in Kassala, Gedaref, Khartoum, South Kordofan, West Kordofan and South Darfur states were also able to prepare for the exams.

In the absence of schools, new initiatives like the Sudan Distance Learning Initiative launched in April, have supported students spread across various far flung locations to revise through weekly lectures broadcasted over TV and radio stations. Students with access to laptops and smart phones were able to watch lessons and lectures uploaded on social media.

“These students are the lucky ones as only a third of refugees [can] access distance learning programmes during the school closures.”

The success of the distance learning programmes has however varied from state to state. Students in states like Kassala, Gedaref and Khartoum, with better access to TV and radio, have benefitted more.

“The learning sessions on Kassala and Khartoum TV channels were very useful,” said Anas Yassin Ibrahim, an Eritrean refugee in Girba camp, Kassala. “I hope to eventually go to university and study to become a doctor.”

For refugee students like Esteer and Fardoos who were cut off from distance learning programmes, the resumption of schools two weeks before the exams allowed them to revise with their teachers, under COVID-19 social distancing measures. Only 15 to 20 students were allowed in each classroom at a time.

Half of the refugee population in Sudan is made up of children under 18, many of whom don’t have access to school and rely on self-studies. For the seven in ten refugees who live outside camps and for many of the internally displaced, providing distance learning has proved to be an even greater challenge.

Overcoming these circumstances is what made this year’s exam crucial to South Sudanese sisters Ekhlas, Sanday and Daniella, who wish to study medicine, law and natural sciences respectively.

“This exam will help us become university graduates, acquire more knowledge and help the poor and needy,” said Ekhlas.

But with all of these efforts to support distance learning, there are still major concerns for refugee learners.

“These students are the lucky ones as only a third of refugee students are able to access distance learning programmes during the school closures,” explained Emily Lugano, a Senior Education Officer based in UNHCR’s regional office in Nairobi. “We are going to have to find ways to help those left behind to catch up.”

She added that while refugee students ordinarily face numerous challenges to get a decent education, the additional challenges that COVID-19 has brought puts them at even more risk.

“We owe a duty to the students to ensure they have adequate support to be successful.”

UNHCR’s education report points to a major concern – the longer children stay out of school, the less likely they are to return once schools reopen, leading to a potentially large number of high school dropouts among refugee learners, particularly girls.

Closed schools mean that students are exposed to a range of protection risks, including sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), early marriage and pregnancy. Children are likely to be distracted from home studywithout schools providing structure and purpose throughout the day. Older children, especially girls, are likely to be tasked with household chores like fetching water, cooking, washing or childcare and may be sent out to work and help provide income for families who may have lost access to livelihoods.

Philip Kumahia, UNHCR’s Education Officer in Takoradi, Ghana underscored the importance of doing more to ensure students can focus on their studies, despite the pandemic.

“Education is the key to success so whether there is COVID-19 or not, we owe a duty to the students to ensure they have adequate support to be successful,” he said.

He added that refugees in their final year of basic education are about to sit for their Basic Education Certificate Exams to qualify for Senior High School. Nearly 80 refugees from four camps have alreadyregistered for the exams, conducted by the West African Examination Council.

“We are really grateful because we have all we need now and we feel confident we will do well in the exams.”

The government reopened schools in June to enable teachers conclude preparations with the students who have been studying at home. The students also receive a hot meal a day and protective kits have been issued in the schools to mitigate the spread of the virus.

“We have equipped all refugee and host community students with learning materials including mathematical sets, pens, pencils, erasers and rulers,” he said, adding that refugees will also receive a transport allowance to ensure 100 per cent attendance.

"I am very happy because I won’t have to borrow a mathematical set from friends,” said Madochee, a refugee student from Egyeikrom camp.

Hannah, a student from the local community added that some parents don't have money to buy exam kits.

“We are really grateful because we have all we need now and we feel confident we will do well in the exams,” she said.

Writing by Catherine Wachiaya in Nairobi with reporting from Sophia Jessen in Khartoum, Emam Mohamed in White Nile, Aida Mohamed in Kassala, Fabien Faivre in Kinshasa and Philip Kumahia in Takoradi.