Sweet homecoming from Smell No Taste

Sweet homecoming from Smell No Taste

SMELL NO TASTE, Liberia (UNHCR) - "I am very sick today," said Stephen Musa. "Something is wrong with me. I took an injection yesterday and one this morning, but it did not seem to help." Stephen was mainly nervous - he was on his way home to Kailahun in Sierra Leone.

"Home sweet home," he murmured while forcing himself into one of UNHCR Liberia's convoy trucks for the last organised repatriation before Sierra Leone's May 14 elections. He had spent the past 10 years with his wife and four children moving from place to place, living in other people's homes. "The church provided us with food and money," he said. "In return I spoke the word of God."

In Dolo's town he spent the last months in a house. "There is no camp in Dolo's town. The place was full of madingo people, many of whom fled recently as they were targeted," he said, referring to the ethnic group that dominated the ULIMO-K party. "We lived in their houses, refugees taking care of other refugees."

Dolo's town, Cotton Tree and Smell No Taste are three villages in Liberia which housed the displaced. Surrounded by flourishing rubber plantations, none of these villages could keep the 176 Sierra Leoneans gathered here from going home.

"A long time ago, people used to smell the good smells from the factory but they were never allowed to taste the food," said Stephen, giving his version of how the name 'Smell No Taste' came into being. "I tasted the food, but still want to return home and eat my own."

Fellow returnee Mojena was separated from her husband and three children in Freetown when she and her other daughter went to visit her mother in Daru four years ago. Fighting broke out and the road between Daru and Freetown was blocked. She headed straight to Liberia, where Hassan, a generous man with a large family in Dolo's town, took her in.

"With the grace of God, I will see my husband again," said Mojena, who was actually dreading to leave the household. She had become attached to Hassan. But when her daughter died in childbirth three months ago, she started longing for home. "I will go to Daru first to see my mother. From there I will send a message to Freetown to find out if my husband has found another wife. If he did, I will return back here."

Like Stephen, Mojena was also feeling sick on this eventful day. Hypertension, she said. She wanted to be transported in the car. But according to a UNHCR field assistant, the doctor had informed her before that her condition was not so severe that it required specific treatment or care.

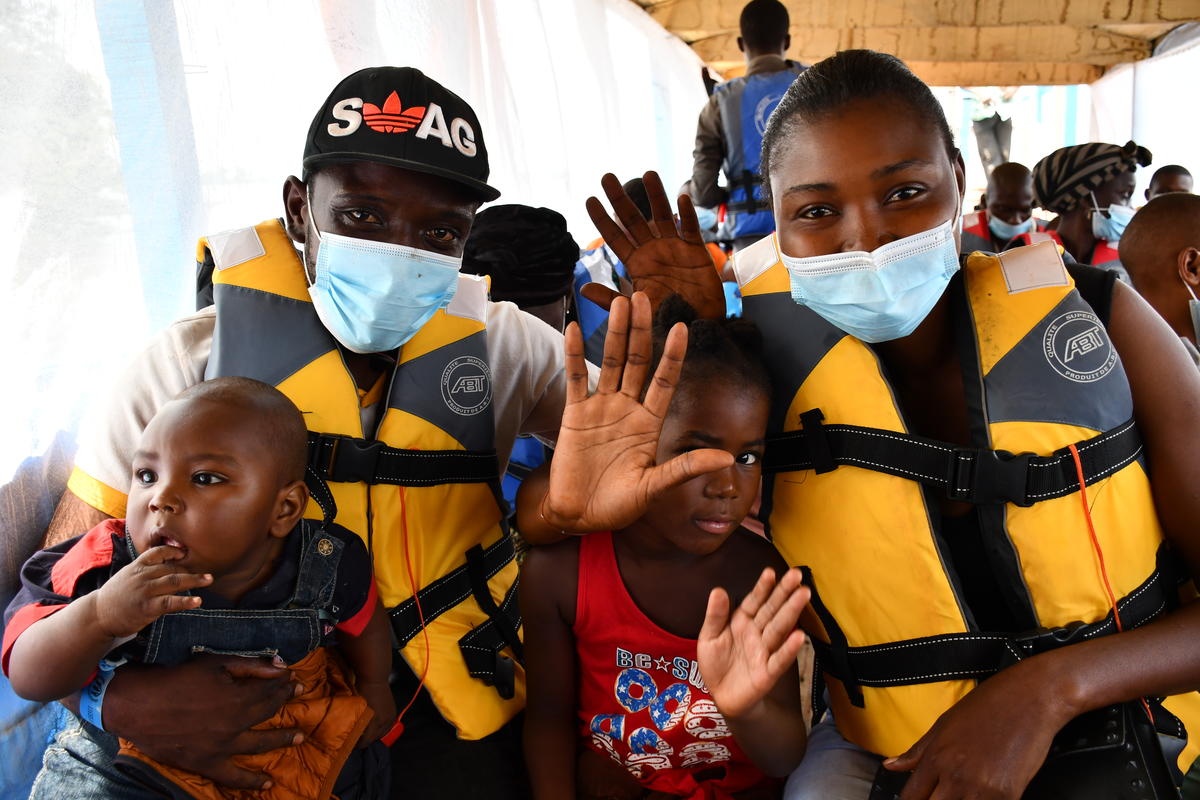

Moses and Brahimi, two brothers from Pujehun, were the only ones not feeling sick. They waved excitedly to those staying behind as the convoy of seven trucks with people and luggage drove off towards Monrovia, away from Smell No Taste, the point of departure.

"This is the last return convoy we will do before May 21," said Anne Gagnepain, UNHCR's Roving Field Officer in Monrovia, of the April 30 convoy. "Operations in the sub region will be stopped for two weeks while Sierra Leone prepares for the elections. So far we facilitated the return of over 10,000 Sierra Leoneans back home from Liberia."

Not all refugees approached UNHCR to assist them in returning home. "If we had the money we would have made our way home earlier, by ourselves," said Stephen. "But we didn't have the money and so we wrote a letter to the embassy of Sierra Leone, which then informed UNHCR."

Hundreds of thousands of Sierra Leoneans fled the country after the civil war started in 1991. UNHCR estimates that since January 2001, over 160,000 refugees have returned home, spontaneously or with UNHCR assistance. Some 135,000 Sierra Leonean refugees are still hosted in Guinea and Liberia.

"I was 6 years old when the rebels entered Pujehun. My uncle was killed in front of me. That is all I remember from Sierra Leone," said Moses, now 15.

The same night their uncle was killed in 1993, the two brothers fled in the dark with their grandmother across the Cape Mount border crossing into Liberia. Their mother was in Bo at that time. Until 1994 they occasionally received news from her. Since then there has been no sign of life. The boys' grandmother died while crossing the border. In Kakata in Liberia, the vice-principal of the Catholic School took the boys in and educated them.

"We had to move again when they attacked Kakata a few weeks ago, together with thousands of others. Then we ended up in Dolo's town," said 22-year-old Brahimi. When asked who attacked Kakata, all laughed nervously. "Who knows?" Brahimi said. Official Liberian government sources said "dissidents" attacked the town, but among the refugees the opinions seemed to differ.

From Smell No Taste, the journey took them three hours, via Monrovia eastwards, past Klay Junction (scene of recent fighting between government troops and the "dissidents") and into Jendema, the town just across the Mano River Bridge. It would take another three to four days for most of them to get to their homes.

Brahimi travelled all the way with a terrorist-style orange woollen hat on, exposing only his eyes. "It is so dusty on the road, I need to protect myself," he said. He could not believe his luck when the trucks entered Jendema. "I am back," he said, "and it feels great."

While the UNHCR officials on the ground finalised their cross-border formalities, Brahimi descended from the truck and ran 2 km back to the point where cross-border traders meet and little shops have been set up. "I have to change my money now. The rate is better here."

Side-tracked by the tempting shops, he nearly missed the trucks' departure from the border. He ran all the way back, arriving just in time, out of breath and sweaty, to hop on the honking trucks.

In Sierra Leone, the convoy was handed over to the UNHCR field office in Zimmi. Led by UNHCR vehicles, they continued over bumpy, windy roads further into country. Two hours later the dusty and shaken passengers arrived, full of vigour, for their overnight stop in Zimmi - they were en route home.

"Everything is ok here", said a bewildered Brahimi, returning from his first venture into town. "I just don't like the food we get here in the camp: bulghur wheat and beans. I did not eat." Later, he found a local lady selling a home-made cassava leaf dish. Overjoyed, he spent his recently-converted money on the delicacy from home.

"Everything is very well," said Stephen, searching for a spoon to eat the bulghur he likes. "I feel so good. Surprisingly ... maybe you were right, maybe I was not really ill this morning, just nervous."

"I am ok," said Mojena, "but my blood pressure is still high: tomorrow I really need to ride in your car."

That night, Zimmi's usually peaceful nights were disturbed by the Sierra Leonean People's Party's campaign disco, which blasted on until 6 am.

The 176 returnees in the transit camp seemed undisturbed the following morning. "I did not mind the noise, I just can't wait to get home," said Stephen, sitting on his bag, impatient for the journey to continue.

The next day the journey continued from Zimmi to Dauda Way Station, near Kenema. Upon their arrival, UNHCR's field assistants handed out kitchen sets, plastic sheeting, tarpaulin, blankets, lamps and other basic items to the returnees to help them survive during the initial months.

From Dauda, Brahimi and Moses would go in UNHCR trucks to Bo, in search of their mother. Stephen would get dropped off in Daru, from where he and his family - with 15,000 leones (US$7) travel allowance per person - would make their own way to Kailahun. And Mojena would be taken to Daru, where she would stay, write and wait in anticipation of news from her husband and children.

There is no place like home, they agreed, as they joined the many Sierra Leoneans who had returned home for the polls. The May 14 elections in Sierra Leone were eventually won by incumbent president Ahmad Tejan Kabbah.

By Astrid van Genderen Stort

UNHCR Liberia