By Mike Woodman, Senior Public Health Officer, UNHCR Division of Resilience and Solutions

For several decades, UNHCR advocated for and has supported refugee-hosting countries as they move towards the inclusion of refugees in their national health systems. Yet, as the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted, many hosting countries are struggling to meet the health needs of their populations due to weak infrastructure and inadequate domestic funding allocations compounded by factors such as a slow post-COVID-19 economic recovery, food insecurity and extreme weather events caused by climate change.

To what extent are refugees currently included in host country health systems?

Refugee access to national health systems depends on the host country’s policies and practices. In some countries, refugees access systems under the same conditions as nationals (subsidized rates or free). In others, refugees can only access services as “foreigners”, often at a higher cost. There are also countries where refugees have limited access to health services due to policies or geographic, linguistic, cultural, and financial barriers.

Good progress but…

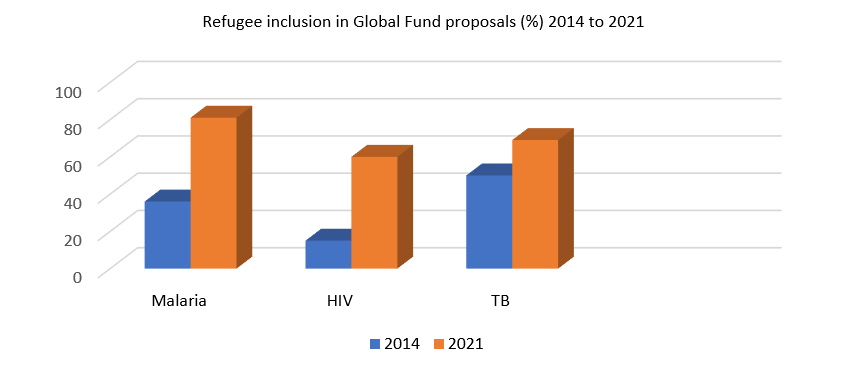

Results from UNHCR’s biannual health inclusion survey of 49 countries indicate that 77% include refugees in their national health plans, up from 62% in 2019. All countries reported that refugees could access primary health facilities, with 94% enjoying access under the same conditions as nationals. However, access is far lower when it comes to receiving care at hospitals, where 17% of countries report no or unequal access compared to citizens. Increasingly, more countries are including refugees in communicable disease programmes and related Global Fund Applications for malaria, HIV and tubercolosis.

Encouragingly, when it came to COVID-19 vaccination roll outs, most governments overwhelmingly supported the inclusion of refugees in national responses – refugees have received vaccinations through national systems in 153 countries.

Social health insurance, one of the strategies towards Universal Health Coverage

Of the 49 countries in the inclusion survey, just under 60% report having a social health insurance scheme. Of those 29 countries with such schemes, only 12 (41%) include refugees. A significant barrier to inclusion is economic sustainability. Insurance premiums must be covered somehow, yet many refugees cannot work to afford the regular payments.

- Rwanda includes urban refugees in Kigali in its community-based health insurance scheme. UNHCR currently covers the cost of premiums for refugees.

- Ghana enrols refugees in its national health insurance scheme under the same conditions as nationals.

- In Ethiopia, UNHCR and ILO are exploring the feasibility of including urban refugees in the community-based health insurance scheme.

- Egypt is rolling out a new national health insurance scheme and UNHCR and ILO are assessing the feasibility of including refugees.

- All Member States in the European Union include Ukrainian refugees in their national health systems on par with nationals following the landmark Temporary Protection Directive. UNHCR supports refugee access to information and monitors access to health services.

UNHCR and ILO have developed a guidance Handbook on social health protection for refugees based on these and other experiences and successful approaches.

Do proven solutions exist for refugee inclusion?

Facilitating systemic change along the humanitarian-development nexus is challenging. Expert panelists at the High Commissioner’s Dialogue session on resilience and inclusion in health in 2020 argued for:

- Coordinated actions to prioritize national systems (e.g., pooled funds, common pay scales, and funding critical inputs for service delivery)

- Rejection of schemes and subsystems inconsistent with universal health coverage

- Long-term perspectives on health financing, stretching beyond the immediate humanitarian phase

Recent evidence and several in depth country case studies are highlighted in The Big Questions in Forced Displacement and Health report released in 2022 by FCDO, UNHCR and the World Bank.

UNHCR is working with development actors and governments on concrete projects

The African Development Bank is leaving no one behind. In 2020, theAfrican Development Bank partnered with UNHCR to strengthen the national COVID-19 responses in the volatile Sahel region (Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Chad). UNHCR procured requested commodities for governments to increase their preparedness and response capacity. The result was strengthened infection control, testing and case management which directly benefited host countries and fostered refugee inclusion.

Scaled health system reform by the World Bank is bringing about inclusion. Mauritania is undergoing a nationwide health sector reform supported by the World Bank (Inaya Health System Support Project ). Additional World Bank financing is allowing for the inclusion of 67,000 Malian refugees hosted in the Mbera camp (Hodh El Chargui). Health services previously supported by UNHCR’s non-governmental partners are being transferred progressively to the Ministry of Health. Camp health centres now have national accreditation, and staff are employed by the Ministry of Health and receive medicine through the national supply system. During this transition period, UNHCR will cover the costs for refugees who cannot afford to pay.

Stark realities require enhanced collaboration

The current outlook for health is grim in many low-income countries hosting refugees. External donors continue to provide most resources, with limited domestic financing leading to higher out-of-pocket healthcare costs. Total health expenditure in many low-income countries falls far short of the WHO’s recommended $86 per capita per year to ensure minimum cost-effective health interventions – an exorbitant amount for both nationals and refugees.

There are three ways the international community could support host countries in including refugees in national health systems:

1. Any effort to make progress on sustainable inclusion will only be possible through medium- to longer-term financial support to build the capacity and resilience of the host country’s health system.

2. Sustainable and effective inclusion of refugees in national services will become a reality when refugees are self-reliant (through livelihoods, education, and other human capital development initiatives) and can contribute to healthcare costs on par with nationals. Social safety nets for the most vulnerable will still be needed.

3. Refugee-hosting countries benefit from inclusive approaches that bring together humanitarian and development funds, and multi-year planning and strategies for health needs to support short, medium and long-term goals.