[Fourth] Assessment of the Situation of Ethnic Minorities in Kosovo (Period covering November 1999 through January 2000)

[Fourth] Assessment of the Situation of Ethnic Minorities in Kosovo (Period covering November 1999 through January 2000)

Executive Summary

This is the fourth joint UNHCR/OSCE assessment on the situation of minorities in Kosovo, covering the period November 1999 through January 2000. The last assessment published on 3 November 1999 concluded that "The overall situation of ethnic minorities remains precarious." Regrettably, three months later this statement still holds true. Kosovo continues to be volatile and potentially dangerous, with ethnicity often remaining a determining factor in the risk of falling victim to crime.

The publication of this report coincides with the disheartening resumption of violence in Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice and several other ethnically motivated attacks elsewhere in the province. As this report was being finalised events in the Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice area included the 2 February attack against a UNHCR bus, leaving two Kosovo Serb passengers dead and a further three injured. This incident triggered further violence resulting in the killing of at least eight people in north Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice the victims being Kosovo Albanian and Turk and a grenade attack against a Kosovo Serb café in north Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice, injuring fifteen Kosovo Serbs. This violence represents a serious setback to UNMIK's efforts to promote freedom of movement and to protect minorities.

Although, as the report shows, serious crime rates have decreased from levels recorded in the previous minority reports, they remain unacceptably high and indicate that ethnically motivated crime continues on a regular basis across the province. One recurring message from the leaders of minority communities is the desire not to be labelled as a minority, as this in itself may lead to increased security risk and hostility.

The report provides a breakdown of minorities by municipality, illustrating how each community has fared during the period under review. Overall, with some limited exceptions, the situation has not improved since the last report was issued and in many instances deteriorating conditions were noted. Minorities remain vulnerable to attack and they do not enjoy the same quality of life experienced by the majority. However the experience has not been uniform for all the minority communities. For the Kosovo Serbs and Muslim Slavs, there are few signs of improvement, while for other communities such as the Roma, Ashkaelia and Egyptian there are some examples of progress having been achieved.

Horrific incidents such as the one on Albanian Flag Day, 28 November 1999, when an elderly Kosovo Serb man was dragged from his car in central Pristina/Prishtina and killed by a mob while his wife and mother-in-law were severely assaulted; the killing of a family of four Muslim Slavs (Torbesh) in their home in Prizren on 12 January; the triple murder of three Kosovo Serbs near Pasjane/Pasjan (in Gnjilane/Gjilan municipality) on 16 January; and, the double murder of two Roma in Djakovica/Gjakove on 15 January as they attempted to protect Roma owned property from unwarranted attack, are a chilling reminder of the dangers faced by minorities in Kosovo. There are numerous and regular other non-fatal attacks and incidents of harassment and intimidation of varying degrees recorded daily. Against this hostile backdrop the minorities of Kosovo struggle to carry on their daily lives.

The report provides an overview of several mechanisms in place to afford protection to minorities. Static security (meaning a permanent KFOR presence in minority areas) continues to be an essential component of minority protection. Although it has had a positive impact on minority communities, these concrete benefits are often not sustainable in the longer term. Nonetheless, in the absence of the acceptance of minority rights on the part of the majority, static security will have to continue.

On the policing front, the report notes that although UNMIK Police continues to benefit from inter-institutional co-operation and comprehensive KFOR support, demand often outstrips supply. Echoing repeated calls from UNMIK, the report highlights that the establishment of the rule of law will be severely hampered if the international police contingent is not brought up from half to full strength. A feature that emerges from the report is the continuing reluctance on the part of minorities and witnesses to crimes against minorities to speak out and report these crimes. This only adds to the wall of silence that is being constructed and puts another obstacle in the path of police efforts.

Alongside physical violence and other criminal acts perpetrated against minorities, the report examines a range of less tangible key issues which impinge on the daily lives of minorities: efforts to establish a functioning judiciary; capacity to participate in political structures and public life; freedom of movement; access to humanitarian assistance; employment and access to essential public services, such as health and education; and property issues.

Efforts to redress the ethnic imbalance in the composition of the judiciary have been hampered by security concerns and reported intimidation. Of a total of 387 judicial appointments announced on 29 December, 90 minority appointments as judges, prosecutors and lay judges were included but a disappointingly low number of these attended swearing-in ceremonies that were held throughout the province in January. Unfortunately for those who did attend, the proceedings were conducted only in the Albanian language. The small number of those who were sworn in, is an indication of the low level of trust and high level of fear still felt by minorities. The report also examines the reverse of the judicial coin: the treatment of minorities suspected of being involved in criminal activities. Although the information to date is not systematic, informal indications point to the greater likelihood of minorities being remanded in custody than members of the majority ethnic group. Fears have also been expressed that minority detainees have in some instances been held in custody with majority detainees, or guarded by a warden of another ethnic group. In summary, the findings illustrate that the lack of a fully independent and impartial judiciary has particularly grave consequences for members of the minority communities.

The extent of political involvement on the part of minorities is seen as an important indicator of the normalisation of life for minority communities. The predominant political issue is currently the establishment of the Joint Interim Administrative Structure (JIAS), a power sharing arrangement between UNMIK and local Kosovars. Although the participation of minorities has been foreseen, this has yet to be achieved. The enlargement of the Kosovo Transitional Council is an additional measure to ensure a greater reflection of the pluralistic nature of Kosovo society at the political level. Efforts at the local level to include minorities in the Municipal Councils and Administrative Boards have varied from region to region.

The degree of minority participation in several institutions, ranging from the Kosovo Police Service (KPS) and the judiciary, to the newly formed Joint Interim Administrative Structure (JIAS) are documented. Concerted efforts to solicit suitable applications from members of minorities for the KPS have met with limited success so far. Ten per cent of the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC) has been reserved for minorities. So far, there have been approximately one hundred applications from amongst Muslim Slavs, Turks and Roma but none from Kosovo Serbs.

Minorities across the province continue to face serious restrictions on their freedom of movement and their access to employment. Few minorities in the province today have jobs. As a result, many are heavily dependent on humanitarian assistance for survival. Similarly, minorities continue to face enormous obstacles in accessing health and education services.

The report highlights several areas where there is a need for concerted efforts to realise long-term strategies designed to address specific issues, such as the mechanism to deal with property restitution under the Housing and Property Directorate and Claims Commission.

The methodology used to produce the joint UNHCR/OSCE reports does not extend to census taking or systematic recording of population figures. Figures, where available are drawn from a variety of sources, including, community leaders, KFOR, UNMIK Police, and beneficiary records for specific projects, and are estimates only. They should not be taken to represent a consensus amongst international or local actors. Estimates for the number of Kosovo Serbs remaining range up to over 100,000. Similar estimates for other communities include around 30,000 Roma (although many more may be present but unreported); up to 35,000 Muslim Slavs; over 20,000 Turks; up to 12,000 Gorani; and some 500 Croats. Final and definitive figures will not be available until such time as a complete civil registration exercise has been undertaken.

Finally, the document presents conclusions and recommendations on action which needs to be taken to address the problems faced by minorities in Kosovo.

In many respects, the protection of minorities remains the litmus test of peace in Kosovo, as it has in all of the wars in the former Yugoslavia. The current lawlessness and culture of impunity regarding ethnic attacks which is documented in this and earlier reports constitutes one of the most crucial gaps in Kosovo today. Until it is brought under control, it will be extremely difficult for UNMIK to achieve its overall mission, or for real development, both political and economic, to move properly forward in Kosovo.

The difficulties confronting UNMIK in rebuilding the rule of law and fostering tolerance in Kosovo are enormous. UNMIK continues to struggle to get a few thousand international police, and has a limited budget to meet widespread costs of administering the province, or to properly repair basic infrastructure. A major investment in the resources needed to establish a basic system of law and order and governance is also urgently needed.

The sustained involvement and support of donor governments, UN agencies and NGOs in these areas will certainly be critical, if any longer-term stability is to be achieved in Kosovo this year. But whatever the international efforts, they can not succeed without more direct, active and responsible engagement of all Kosovars in the whole process of re-establishment of law and order, tolerance, and a pluralistic society. Undue expectations that "the internationals" will do it all must be replaced by a proper sense of reality and shared responsibility, if these major and pressing challenges in Kosovo are to be met, and if we are not to continue publishing reports such as these for the foreseeable future.

Methodology

This report, represents the joint efforts of UNHCR and OSCE to monitor and assess the prevailing situation for ethnic minorities remaining in Kosovo, and in doing so attempts to draw certain conclusions about their current predicament and to suggest ways forward that would address their protection needs. It is the fourth in an ongoing series produced by UNHCR and OSCE.

The report draws widely on field reports compiled by UNHCR Protection Officers and OSCE Human Rights Officers, in response to a specific questionnaire sent out for this purpose. Field staff were encouraged to reach out into the minority communities and record the daily realities of their lives. Reporting covered not only the violent crimes that continue to be perpetrated against the lives and property of individuals and communities as a whole, but also the obstacles that they face in exercising their most basic of rights. Obstacles of such a nature that daily life becomes difficult and in some cases impossible, ultimately leading to insurmountable fear and ongoing displacement.

Field staff were similarly encouraged to highlight examples of tolerance and inter-ethnic co-operation whenever and wherever they came across such. It is important to recognise instances in which inter-ethnic co-existence has been sustained, even where these may be limited in impact. We do not want to overlook the potential which exists within some communities, in certain locations to regain stability and return to a more normal existence. In addition, the report draws on complementary information in the form of reliable media analysis and other relevant sources and benefits from knowledge gathered through the working mechanism of the Ad Hoc Task Force on Minorities, an inter-agency group comprised of representatives of the key institutions involved in different aspects of minority protection.

Issues of particular relevance and concern

In the fulfilment of their respective mandates UNHCR and OSCE understand the term protection to encompass the full range of basic rights that any individual, regardless of ethnicity, sex, race, religion, political affiliation or any other social, economic or physical distinction, is entitled to have respected permitting them to live in conditions of safety and dignity. It is against this backdrop that UNHCR and OSCE approach the subject of the protection of minorities in Kosovo. Crimes committed against minorities are perhaps the most visible evidence of their predicament in Kosovo today but a far wider range of issues has to be looked at to grasp the full extent of the challenge faced by Kosovars, with the support of the international community as a whole. We highlight here the more relevant issues in this regard. Those that require particular attention if Kosovo is to become a functional society, within which the rights and obligations of all citizens can be exercised. Immediately following on from these brief snap-shots of the main issues of concern, we set out information by ethnic minority group which will serve as an overview of how each group has fared over the intervening period since the last report, both in the negative and the positive sense, illustrating this by examples cited by our field staff.

Static guards

Static guards, as exemplified by KFOR patrols permanently assigned to protection duties, continues to be needed to safeguard lives and property. On January 18th KFOR stated that their most important mission is to provide a safe and secure environment for all the people of Kosovo. KFOR informs, that around the clock in communities throughout the province there are some 750 patrols on foot and in vehicles. In addition static guards are deployed at 550 important sites such as churches, homes and businesses and over 200 checkpoints at permanent and varying locations. Every day two out of three soldiers are assigned to security operations aimed to crack down on crime and violence. It should be noted that whilst efforts of this magnitude are not exclusively for the benefit of minorities, in large part they are for all intents and purposes geared towards minority protection.

However the benefits of such activities, both real and perceived, can be short lived. As such high levels of static security are unsustainable, over reliance on them can lead to a false sense of security that can not be maintained. For instance, as a result of a strategy discussed by the Ad Hoc Task Force in early November 1999, it was recommended that a permanent KFOR checkpoint be installed close to Recane/Recan, in the Zhupa region, to protect the interests of the Kosovo Serb minority there. This recommendation was made in view of the fact that existing efforts to provide security through regular patrols had proved ineffectual, since the wrongdoers simply waited for the patrol to pass before carrying out acts of violence and intimidation. During September and October 1999 a string of serious incidents had been recorded but the situation was calmed considerably after the installation of the checkpoint. The checkpoint was well received by the local population who commended the performance of the soldiers manning it. However, it was withdrawn on December 18th apparently because KFOR perceived it to be ineffectual. Locals expressed their concern that the service had been withdrawn so suddenly without their having been consulted or informed. In this instance concerns that the situation would revert to pre-checkpoint conditions were allayed through the use of alternative KFOR patrolling mechanisms and the establishment of an UNMIK Police sub-station. In another example however, the Orthodox church in Cernica/Cernice, Gnjilane/Gjilan Municipality was damaged in a bomb attack on the night of January 14th shortly after KFOR had withdrawn a static guard.

The fact that KFOR is obliged to maintain such intensive efforts to safeguard minority protection is indicative of the security situation still faced by minorities. There is no doubt that continued KFOR involvement is demanded by the harsh realities on the ground and their efforts in this regard are welcomed by minority communities. Budgetary and personnel constraints, however, mean that it is not possible to provide the levels of static security that would be needed to fully safeguard the lives and property of all minorities province-wide. Static guarding however, as a response to imminent threats is often the only way to protect such overriding rights, as that to life and liberty. The immediate impact of this on the beneficiaries is generally welcomed but if such measures have to be continued to the extent that normal life is not possible, these same beneficiaries are likely to come to resent the fact that they have to live under constant guard and may opt instead to move to a safer location within Kosovo or further afield. Such security efforts can not succeed in isolation. They have to be seen as an integral part of broader efforts to improve the overall security situation encompassing acceptance of minority communities by their majority neighbours, including full respect for their rights.

Policing

Kosovo is a post-conflict area struggling to re-establish rule of law. The essence of protection being the ability of all citizens to fully exercise their basic rights, it follows that this can only occur within the framework of a stable society which accepts this principle and collectively determines to respect it. Rule of law is of primary importance in this regard since it is only through effective policing and subsequent administration of justice, that the efforts of civil society to fulfil their obligations can be supported or their failures addressed and punished.

The brunt of the work required to re-establish rule of law is naturally borne by the police. They in turn need to be adequately supported by the judiciary. UNMIK police, continues to benefit from the comprehensive back-up of KFOR, many of KFOR's activities in this regard having been highlighted above. This inter-institutional co-operation is vital in maintaining levels of policing capable of responding to the heavy demands. Unfortunately, the demand is such that it threatens to outstrip the supply. As of January 31st some 1,970 police officers of various nationalities were available province-wide. This includes deployment of 208 officers to Pristina/Prishtina Main HQ, 599 in the greater Pristina/Prishtina area, 311 in the Prizren area, 101 in the Pec/Peje area, 258 in the Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice area, 181 in the Gnjilane/Gjilan area and 199 at border points with the balance of officers in training and other activities. This number is well below the figure of some 4,718 officers authorised, and whose full deployment the SRSG has repeatedly called for.

Members of the newly established Kosovo Police Service (KPS), have already taken up policing activities. These local officers undergo a five week course at the Kosovo Police Service School in Vucitrn/Vushtrri, followed by a 19 week field training programme, mentored by international officers. Concerted efforts have been made to solicit suitable applications from minority groups and to fully support their incorporation into the KPS since any properly functioning police force has to draw on all sectors of the community. Of the first 173 graduates there were eight Kosovo Serbs, three Muslim Slavs, three Roma and three Turks. A further intake of 177 persons is undergoing training including a greater number of minorities (27 Kosovo Serbs, three Muslim Slavs and seven Turks). The establishment of a local police force is a major step forward. From the point of view of minority protection, however, it poses some challenges, namely that of instilling in the KPS majority recruits an understanding of the need to protect minorities and of having all sectors of the population respect a multi-ethnic police force.

A few members of the KPS have been dismissed from their duties for unacceptable behaviour including in some cases the commission of acts amounting to victimisation of minorities. KPS members themselves have faced difficulties in the performance of their duties. In an incident in Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice on November 2nd a female Kosovo Albanian cadet had her nose broken and her international tutor was relieved of his weapon during a scuffle involving Kosovo Serbs. This incident highlights the difficulties that will be faced in having minority groups accept the authority of a police force largely comprised of members of the majority ethnic group. In another incident a Kosovo Albanian cadet was abducted for a brief period in late November, possibly indicating the type of pressure KPS members can expect from their own community.

An important aspect linked to the question of policing is that of widespread reports that former members of the KLA and/or provisional members of the Kosovo Protection Corps (KPC, TMK by it's Albanian acronym), or persons claiming to be such, continue to be engaged in irregular and illegal policing activities. Reports from the field frequently refer to cases of illegal detention and interrogation at the hands of persons claiming to be KPC members, or suspected as such by victims, due to the fact that they are uniformed. However, the source of information is often unconfirmed and even when direct victims of such crimes can be identified they are too afraid to report them for fear of reprisals. This fact makes it very difficult for KFOR or other relevant authorities to pursue these cases and take appropriate action where it can be confirmed that KPC members are involved.

UNMIK Police deployment varies from place to place, determined by the number of officers available. The lack of sufficient personnel hampers the ability of the police to serve the needs of the population, minorities in particular. For instance at time of writing, with only nine officers on the ground in Djakovica/Gjakove, a town of approximately 120,000, with a substantial Roma population, frequently targeted as crime victims, UNMIK Police response mechanisms prove inadequate. Similarly in Urosevac/Ferizaj repeated calls for the establishment of a sub-station to benefit the remaining Roma minority in the urban centre, have not been met with a response due to lack of available resources. Despite the very real obstacle of lack of resources, UNMIK Police do recognise the need to ensure effective deployment in areas of sensitivity for ethnic reasons. Through their active participation in the Ad Hoc Task Force, a mechanism has been attained whereby recommendations, akin to those directed to KFOR on static security, are welcomed by UNMIK Police and efforts are made to respond accordingly.

KFOR and UNMIK Police jointly produce statistical information on crime rates including some information specific to the impact on minority groups. Crime rates alone, however, do not tell the full story and given the potential for fluctuation from week to week or from area to area, can sometimes even lead to a false sense of security only to be followed by a crushing setback. For instance an anticipated increase in ethnically motivated crime over the holiday period, was successfully contained by concerted and co-ordinated efforts on the part of KFOR and UNMIK Police. The figures for mid January however, put the holiday calm in stark relief. Thirteen persons were reported murdered from January 12th through 17th including the murder of a family of four Muslim Slavs (Torbesh) in their home in Prizren on January 12th, the triple murder of three Kosovo Serbs close to Pasjane/Pasjan, in Gnjilane/Gjilan on January 16th and the double murder of two Roma in Djakovica/Gjakove on January 15th while they attempted to protect Roma owned property from unwarranted attack. There can be little doubt that the ethnic factor was an important, if not the sole motivation in some of these incidents. Furthermore such figures serve to underline just how volatile the situation remains in spite of the fact that clear improvements in re-establishment of the rule of law can be cited.

Organised crime elements appear to be taking hold. While organised crime for economic gain is unlikely to recognise ethnic distinctions, putting Kosovo Albanians equally at risk, this development is particularly worrying for ethnic minorities since crime tends to disproportionately affect the vulnerable and there is no doubt that ethnic minorities face heightened degrees of vulnerability. The rising spectre of organised crime for power based reasons is more worrying still. Again all ethnic groups could be at risk, but minorities more so, suffering not only the direct consequences of being the victims of such crime but also the negative impact of a decreasing level of potential solidarity and condemnation coming from within the majority population, increasingly concerned for their own safety and afraid to speak out. There is already talk of a silent majority within Kosovo, who reject the violent acts committed against minorities by the masked and the unidentified claiming to act in their name and on their behalf. There is a serious risk that this important sector, which could reasonably be expected to be a moderating influence for the good of all will be silenced further still by the threat of violence. If this transpires, it will be a high price indeed for all of Kosovo's residents to pay but will be particularly hard-felt by the minorities.

Functioning of the legal system

The absence of a functioning judicial system is one of the greatest challenges facing Kosovo. The impact is felt acutely by all but the lack of a fully independent and impartial judiciary has particularly grave consequences for members of the minority communities. If there is no means of addressing the violence against them or providing redress, those members of minority communities suffer from a double violation of their rights. Moreover with no avenue of redress there is no deterrent to those who wish to perpetrate crimes against the minority population. That creates the conditions in which a vicious cycle of impunity emerges.

During the first stages of this reporting period the Emergency Judicial System continued to operate with thirty criminal law judges, five civil law judges and twelve prosecutors covering the entire province. Of these, there were only three Muslim Slavs and one Turk, none of the Kosovo Serbs appointed to the Emergency Judicial System having remained in their posts beyond early October 1999. Efforts to redress the composition of the judiciary and to improve minority participation were taken in the recent rounds of judicial appointments. During the process leading up to the appointments however, the difficulties of persuading minority members to participate in the judiciary became apparent. For example whilst the administration in Gnjilane/Gjilan had hoped to receive up to six Kosovo Serb candidates for judge and prosecutor posts and up to twelve as lay judges, in the event only five Kosovo Serbs filed applications and these were concerned about their safety in attending for interviews in Gnjilane/Gjilan without security escort.

Despite difficulties of this type by December 29th 1999 UNMIK was able to announce the appointment of 387 judges, prosecutors and lay judges province-wide, including, 11 Kosovo Serbs, five Muslim Slavs, one Turk and one Roma appointed as judges and prosecutors and 35 Kosovo Serbs, 23 Muslim Slavs, eight Roma and six Turks appointed as lay judges. The initial swearing in ceremonies took place during January 2000, with a disappointing low number of the appointed minority judges attending the ceremony. Of a total of 180 judges sworn in only 8 were minorities, of 73 lay judges only 13 were minorities and of 39 prosecutors only 2 were minorities. Moreover, for those who did attend the swearing in ceremonies, the proceedings were conducted only in Albanian and the oath was not translated into Serbo-Croat. The shortfall between the number of appointed judges from minority groups and those actually sworn in belies high levels of fear for their personal security

At the time of writing, the swearing in of members of the judiciary for Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice is still outstanding. In the initial appointments, two Kosovo Serbs and one Muslim Slav were appointed to the District Court and one Kosovo Serb to the Municipal Court. The announcement of the appointments was followed by a series of demonstrations against what was seen by the Kosovo Serb community to be under representation of Kosovo Serbs amongst the appointees. The demonstrations were at times violent, resulting in one person being injured and a window in the court building being broken. On January 21st an agreement was reached between the Kosovo Serb representatives and the UN Civil Administration that would result in greater Kosovo Serb representation in the judiciary. The swearing in of the judges has been postponed until agreement is reached with the Kosovo Albanian community and the approval of the SRSG is given.

There has been no systematic analysis undertaken as to how minorities are treated when they are the suspected perpetrators of crime. However observation in the field indicates differing treatment meted out to minority and majority population when it comes to decisions on detention and prosecution. In mid January figures for arrest, detention and release revealed that of a total of 3,747 persons detained by KFOR, only 271 remained in the 5 detention facilities operative in Kosovo. Within the Emergency Judicial System, from July 1999 through to January 17th, 862 persons were brought before investigating judges, and 368 of them were released (42.6%). In some cases detainees were being released or alternatively subjected to prolonged detention, on what would appear to be the basis of their ethnicity. This tendency not only brings the judiciary into disrepute, it undermines the ability of the police to do their job effectively. Minorities appear to be more likely to be kept on remand in custody while members of the majority ethnicity may be released even where the evidence against them is strong. It is perceptions of this type that have undermined the authority of the judiciary in the eyes of many members of minority communities, leading to questions about their impartiality. In the current climate where local judges may be subject to pressure in sensitive cases involving suspects or victims of different ethnicities, the ability of the judge to administer justice fairly and impartially, and solely on the basis of legal considerations may be called into question. As an interim measure the introduction of international judges and prosecutors particularly for ethnically related crime would add legitimacy to the judicial process, pending the establishment of a fully functional local system.

Disputes over the codes and procedures to be upheld by the judiciary have also hampered UNMIK's ability to rapidly establish an effective judiciary. Initially Kosovo Albanian judges and prosecutors rejected the decision that the applicable law in Kosovo should be that in force March 24th 1999 (at the beginning of the NATO air campaign), subject to observance of internationally recognised standards. Subsequently on December 12th, the SRSG passed Regulation No. 1999/24 and Regulation No. 1999/25, repealing Section 3 of Regulation No. 1999/1 and providing that in "criminal proceedings, the defendant shall have the benefit of the most favourable provision in the criminal laws which were in force in Kosovo between March 22nd 1989 and the date of the present regulation." This regulation enables the application of the Kosovo Criminal Code and other regional laws which had been suspended in previous years. The reaction of judges and prosecutors from minority communities on the question of applicable law has not been welcoming.

Another factor that has impeded the capacity of the judicial system to offer effective protection to the minority community is the rule whereby the written statements of witnesses, or witness statements taken by members of KFOR or UNMIK Police, are not admitted in evidence as they have not been verified orally before an investigating judge. Where witnesses and/or victims have fled Kosovo, as has happened with minority victims fearing for their future safety, their evidence is excluded from the prosecution file. The same applies where a KFOR soldier or UNMIK Police Officer who made or took a statement has been rotated out of the province at the time the investigating judge comes to examine the case file. This can result in cases being dismissed and the perpetrators of crimes going free.

With reference to minority detainees, fears have been expressed that their safety could be jeopardised if they are kept in detention facilities, staffed by Kosovo Albanians and where they mix with detainees from the majority group. This problem may be resolved by transfer to another area as was the case with Kosovo Serb detainees moved from Prizren to Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice. This however can have the knock on effect of complicating access by family visitors and/or legal representatives.

The extent to which minority communities have access to legal advice and representation would appear to be limited, although it is difficult to draw conclusions in the absence of clear information on practising lawyers from minority communities. The UNHCR funded Legal Aid and Information Centres operated by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is one example of an attempt to cover this need.

Access to political structures

An important indicator of the normalisation of life for minorities is the extent to which they are politically active or have access to public life. At the time of writing the predominant political issue on the agenda, is the establishment of the Joint interim Administrative Structure (JIAS). JIAS was created through agreement signed on December 15th 1999 between the SRSG and three Kosovo Albanian political parties, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), the Party of Democratic Progress in Kosovo (PPDK), and the United Democratic Movement (LBD). Whilst the Kosovo Serb political representatives were informed and invited to participate in the discussions leading to this initiative to date they have not signed the agreement. Efforts are ongoing to encourage full minority participation in this important political forum.

The regulation establishing the JIAS, Regulation No. 2000/1, provides that "all communities of Kosovo shall be involved in the provisional administrative management" and that there shall be "a fair representation of all communities". To achieve this the framework provides that there shall be one seat for a member of the Kosovo Serb minority in the Interim Administrative Council (IAC) and four of the nineteen Administrative Departments will be co-headed by members of the minority communities: two by Kosovo Serbs, one by a Turk and one by a Bosniak. The Departments that minorities will co-head are Labour and Employment, Transport and Infrastructure, Agriculture, and Environment. There is also provision for a Special Expert Committee on Security composed of UNMIK and local experts to be directly attached to the Interim Administrative Council. The remit of this Committee will include the situation of minorities. Efforts to ensure full the participation of minorities are mirrored at the Municipal level where administrative functions are to be performed by a Municipal Administrative Board, appointed by the UNMIK Municipal Administrator, which is to consult with a Municipal Council. The members of the Municipal Council should represent the citizens of the municipality and be appointed by the Municipal Administrator. The establishment of both of these bodies across the province is currently underway, and as such there is no clear picture at the time of writing of what the final composition in each municipality will be.

The Kosovo Transition Council will be enlarged to include more minorities. This means that there will be at least three extra places for Kosovo Serb representation, and possibly four. The fourth place may be for 'independent Serb' representation. There will be two places for Turks and two places for Muslim Slavs; most likely one will be drawn from the Gorani community, the other from the Bosniak community. There will also be one place for a Roma representative.

The Kosovo political scene is characterised by many fractious parties from the two main communities - the Kosovo Albanians and the Kosovo Serbs and a number of smaller parties which represent other minority communities. The Kosovo Serb population is in the main represented by two coalition groups - the Kosovo Serb National Council (Srpsko Nacionalno Vece: SNV) and the Kosovo Serb National Assembly (SNA). The leading representatives of the Turkish population are the Turkish Democratic Union (Turk Demokratik Birligi Partisi: TDBP) and the Turkish People's Party (Turk Halk Partisi: THP). The Bosniak community is represented by the Party of Democratic Action (Stranka Demokratske Akcije: SDA) and the Muslim Reform Party. The Roma community has the least obvious representation or at least not in the form of an ethnic specific party. Given the diverse nature of the Roma population, it is not clear that any one party could represent the diverse interests of the constituent communities - the Roma, Ashkaelia, and the Egyptians. However in December 1999, a political party was established in Urosevac/Ferezai, the Ashkaelia Democratic Party of Kosovo whose stated aims include representation for the entire Roma population.

Beyond formal political fora, encouragement is also being given to minorities to participate in broader aspects of civil society. The creation of new NGOs which include or cater for minority communities, combined with the provision of capacity building for them is one such development. Plans are in place to hold training and capacity building programmes for those NGOs from minority communities in Spring. In Prizren there is movement from within both the Muslim Slav community and the Turkish community to establish and register NGOs and from the Kosovo Serb communities many requests from youth groups have been received. The youth groups are seeking advice on how to establish and run different types of associations. One concern expressed by some NGOs however is the policy whereby NGOs based in other parts of FRY and operating in Kosovo have to register as new Kosovo NGOs or as international NGOs if they want legal recognition in Kosovo. This causes problems for the Kosovo Serb minority in particular

Encouragement to the Roma community to strengthen their voice through the establishment and creation of civil society institutions is of particular interest. With support from OSCE, the Ashkaelia community in Podujevo/Pudujeve, has created an NGO called "Democratic Hope", currently in the process of being registered with UNMIK. This organisation is already carrying out several activities, in the fields of education, culture and employment and a mediators has been appointed to interact with local authorities. Similarly in Djacovica/Gjakove the "Albanian-Egyptians of Kosova" organisation was recently inaugurated. An OSCE initiative to establish "Citizenship Forums" is another means of allowing minorities access to power structures. Pilot programmes for the "Citizenship Forums have commenced.

Access to and treatment by the Media

Another essential indicator in civil society for gauging the capacity of minority communities to participate in public life is the media. Consideration needs to be given on the one hand to the extent to which minorities have a voice through the media, and on the other hand how the media portrays minorities, through the way they report on their communities and issues affecting them. There have been incidents during the reporting period of inflammatory articles appearing in the print media. One recent example involved the publication of a list of persons, minorities and Kosovo Albanians alike, accused by the article of collaborating with the police and military forces against the interests of Kosovo Albanians, before and during the conflict. The author in that case was a provisional member of the KPC, now conditionally holding a senior post in the Information Department. Regulation No 2000/4 of February 1st on the Prohibition against Inciting to National, Racial, Religious or Ethnic Hatred, Discord or Intolerance may help to address problems of this type.

In the print media the Muslim Slavs have two publications based in Prizren, one Selam, a bi-monthly review dedicated to the Bosniak community and the other a new publication Kosovksi Avaz, a weekly Bosniak publication. The Turkish community also have their own paper called Yeni Donem. The Roma do not have any identifiable specific access to their own print media. In the broadcast media, indigenous TV broadcasting, still nascent in post-war Kosovo, is provided by Radio Television Kosovo (RTK) which has a 10 minute news programme in Serbo-Croat scheduled in its three hour daily broadcast. Radio broadcasting has a broader base. There are essentially two different types of radio broadcasters: radio stations which broadcast wholly in one language, for one particular population, and radio stations which have slots in their main programming for news or cultural programmes targeted at the minority populations. For the Kosovo Serb population, the largest concentration of radio stations, eight in all, is in Northern Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice. Radio Gracanica, broadcasting in Serbo-Croat from Gracanica, is part of Grupe S, a Belgrade based conglomerate that owns a number of radio stations operating in Kosovo. In Gnjilane/Gjilan, Radio Max also serves a Serb audience. There are also a number of stations, supported by sectors of the international community, that broadcast in both Albanian and Serbo-Croat, for example Radio Galaxy (run by KFOR) and Radio Bluesky (run by UNMIK). Radio Kaminica, created by KFOR in October 1999 also broadcasts in both Albanian and Serbo-Croat and Radio Contact a local Pristina/Prishtina station broadcasts in Albanian, Serbo-Croat and Turkish. In Pasjane/Pasjan there is a proposal for another station which would broadcast in both Albanian and Serbo-Croat. For the Muslim Slav population, Radio Sharri, broadcasts in both Albanian and Gorani but employees have expressed their concerns that there is some danger in broadcasting songs in Gorani. Radio Prizren reserves one hour of its daily schedule for Turkish language programmes and half and hour for Serbo-Croat programming.

Freedom of movement

Minorities continue to suffer from serious restrictions on their freedom of movement, as is illustrated in the sections by ethnic group to follow. Limitations on freedom of movement can range from being totally housebound in the absence of a security escort to being able to move within a restricted area inhabited by members of the same group but needing a security escort to venture further afield in ethnically mixed areas.

Freedom of movement is a basic right, the availability of which will determine one's ability to exercise a whole range of other rights, such as access to health care, education and other services. Where freedom of movement is restricted, life can become difficult, unbearable and ultimately unsustainable, leading people to seek other alternatives. Unfortunately this is a factor that continues to contribute to ongoing displacement within Kosovo and also to long term departure. Departures from Kosovo have drastically reduced from the levels witnessed in earlier reporting periods but continue nonetheless on a lesser scale. Many minority communities have now stabilised having survived a traumatic period of displacement but now find themselves faced with unacceptable restrictions on their freedom of movement leading them to question whether there is any future for them within Kosovo. Freedom of movement requirements need to be addressed on two levels: freedom of movement within Kosovo itself and cross boundary freedom of movement further normalising links with other parts of FRY.

In an effort to alleviate the hardships of the most affected communities UNHCR has provided bus services to facilitate freedom of movement. As this report was being finalised a fatal attack on one of these services, on February 2nd, resulted in the death of two Kosovo Serb passengers and has led to the suspension of all services pending further investigation and security review. The Danish Refugee Council, UNHCR implementing partner for this project operated eight bus routes at different locations around Kosovo, all of these requiring KFOR security escort. Some of the routes were able to introduce an inter-ethnic component as a small step towards confidence building between the different communities, by virtue of the fact that they service passengers of different ethnic groups. Progress in this regard has been limited with little evidence of passengers of differing backgrounds interacting socially while riding the bus and some indications that they choose not to board the bus if they consider the ethnic balance of the passengers not to be in their favour. Other routes are entirely mono-ethnic and operate under difficult security conditions simply to allow people to move and avail themselves of basic services, in an attempt to contribute to a general calming of tensions and breaking down the siege mentality that is so strong in some places. While operational these services provided a much needed lifeline to isolated minority communities and were much appreciated by the population. The February 2nd attack represented a major setback to UNHCR's efforts to promote freedom of movement and to UNMIK's efforts to protect minorities more generally. The re-activation of this project is under consideration at the moment.

In addition to UNHCR efforts there also exist initiatives on the part of other actors, for example KFOR provides security escorts to commercial bus lines serving minorities and periodically provides specific escorts to minorities travelling in their own vehicles.

As an additional measure to alleviate the sense of isolation and abandonment felt by many minority communities facing freedom of movement difficulties, UNHCR funds a project operated by Telecoms Sans Frontières to make satellite phone services available on a periodic basis. This project has benefited many communities throughout Kosovo and was particularly welcomed in the aftermath of the fatal bus attack when many Kosovo Serb families were desperate to communicate with their relatives elsewhere to assure them that they were safe.

Humanitarian assistance

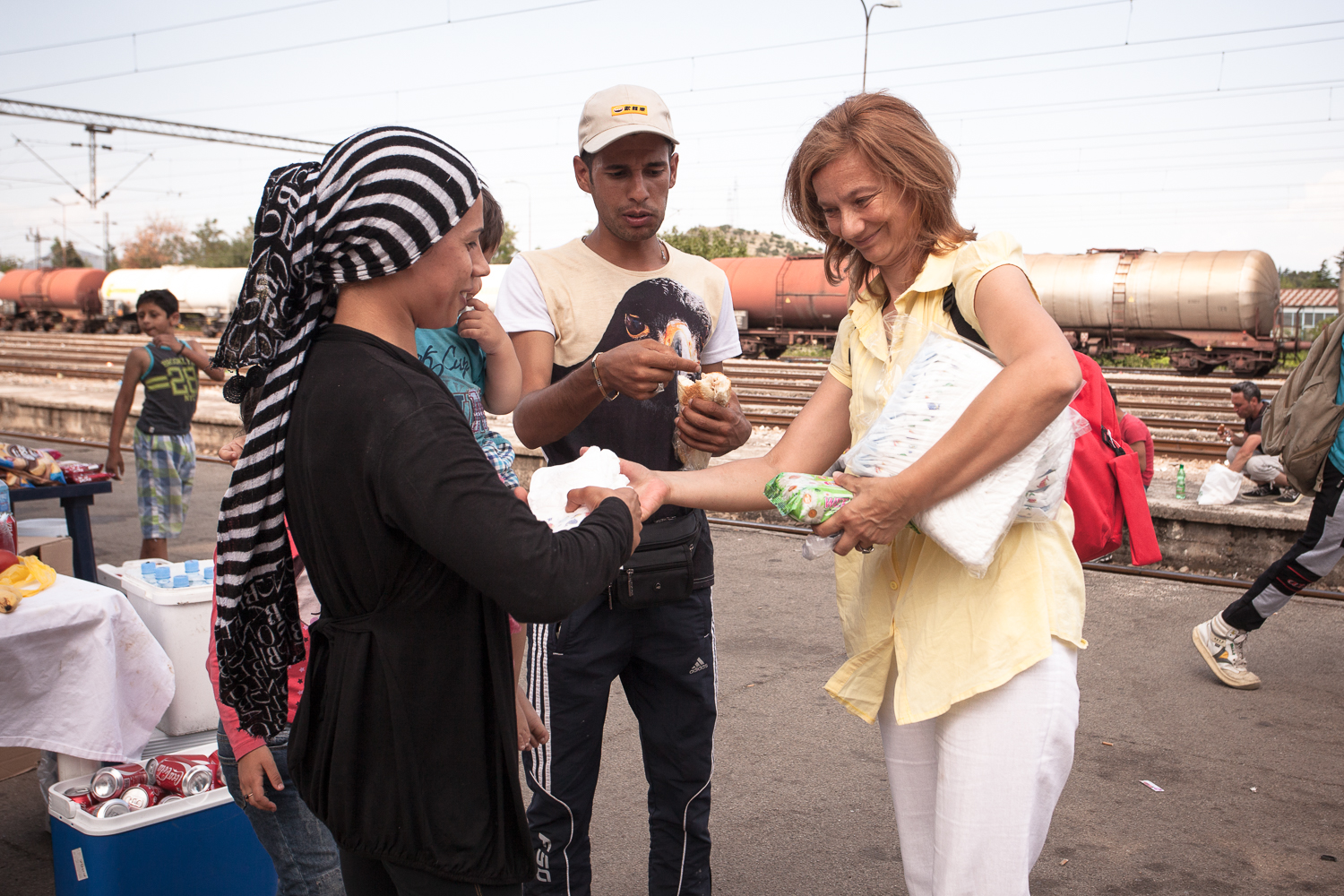

UNHCR and a range of other actors continue to provide humanitarian assistance to minority groups, on the basis of need. Monitoring mechanisms have been developed to ensure that minorities have appropriate access to such assistance. In stark contrast to the majority population, some minorities have been so cut off from the possibility of employment or agricultural production, that they have been reduced to the status of welfare cases with no option but to seek out assistance from whatever sources are available. This situation presents a major challenge not only because of the difficulties that will be faced by humanitarian agencies in sustaining adequate levels of assistance in the long term but also because of the demoralising effect it has on the beneficiaries, who will inevitably grow restless at the fact that they have lost control over so many simple aspects of their lives. This type of resentment can also manifest itself on the part of the majority population sometimes jealous of assistance given to minorities which they perceive to be not equally provided to them. In addition, in certain high risk areas providing assistance can often identify minority members who are otherwise keeping a low profile and expose them to risk. Humanitarian agencies such as UNHCR and others will have to be alert to such sensitivities in ensuring the delivery of appropriate humanitarian assistance that genuinely serves the interests of minority groups. A joint WFP/UNHCR assessment on the Food Needs of Minorities in Kosovo, conducted during November 1999 and based on extensive field monitoring bears out many of these concerns with respect to the delivery of food aid in particular.

Field based research highlighed the difficulty faced in some areas in finding reliable local partners to assume responsibility for the delivery of assistance to minorities and to do so in an impartial and sensitive way. At present in Kosovo, UNHCR has been obliged to rely heavily on international NGOs for this task. This makes distribution more labour intensive and complicated. UNHCR constantly monitors the performance of its implementing partners, to ensure that they are up to standard and where problems of discrimination in delivery of assistance are detected, moves rapidly to rectify this. This in turn is a labour intensive and demanding task but one which is undertaken as a matter of routine in order to ensure that assistance is delivered exclusively with reference to humanitarian and apolitical criteria and does not become the subject of further discrimination.

Shelter is another important component of humanitarian assistance which may be required by minorities. In some instances minorities have been displaced, requiring the provision of temporary emergency accommodation on an individual or group basis, whilst in others they have managed to remain in their homes, albeit under very difficult security conditions but they require basic repair materials to patch up the structural damage caused by attacks against their property.

This reporting period saw some improvement in the living conditions of displaced Roma who had been living in tented camps in, Obilic/Obiliq and Zvecan. These persons have been moved to hard shelter better able to withstand the harsh winter conditions but they remain in a state of displacement with little prospect of returning to their homes of origin in the near future. Many displaced persons have witnessed or subsequently heard of the destruction of their homes, as was the case with a group of Roma displaced to Coloni within Djakovica/Gjakova municipality in early November as a result of constant harassment culminating in the non fatal shooting of one member of their community. Having initially expressed a desire to return home quickly with the benefit of KFOR security presence they were given the sad news that some of their homes had already been burnt, in the short space of time they were left unoccupied. This group opted to remain in the relative safety of Coloni under permanent KFOR guard, for the duration of the winter and will reassess the possibilities of returning home in the spring.

UNHCR and other actors will continue to try to satisfy the immediate needs of minorities, with emergency rehabilitation assistance pending the provision of durable reconstruction programmes by other actors. However it has to be noted that in many instances these persons will not enjoy the same possibilities as many of their Kosovo Albanian counterparts to look forward to reconstruction in the spring. They face the sad reality of continued displacement because it is not only the destruction or illegal occupation of their property that prevents them from going home, but the intolerance of their neighbours and overriding security concerns.

Property issues (Housing)

The need for a long term strategy in terms of property restitution is also apparent. UNMIK regulation No. 1999/23 dating from November 15th on the Establishment of the Housing and Property Directorate and the Housing and Property Claims Commission, marks the most important step forward in this direction. The mandate of the Directorate and Commission will obviously be far reaching for minorities recently displaced and for Kosovo Albanians and others whose property rights were violated over the past 10 years. By focusing first on mediation rather than adjudication, it is hoped to provide a less confrontational means of resolving property disputes, in particular where they arise between minority and majority owners. For minorities who have been displaced the establishment of an independent body to determine property claims will play an important role in their ability to either return to their homes, to be able to sell them or receive fair compensation.

Funding shortages delaying the implementation of Regulation No. 23 have been partially overcome by a six month funding commitment on the part of the Finnish government. This money will allow the relevant authorities to activate the Housing and Property Directorate and Claims Commission by establishing premises, hiring staff and starting on the task of receiving and adjudicating claims. There is no doubt that this will be a lengthy and difficult process, in view of the loss and destruction of much supporting documentation, but a process that will prove crucial to the longer term objectives of respecting individual and communal rights regardless of the ethnicity of the beneficiary. It is urgent that the implementation of Regulation No. 23 be accelerated and be accompanied immediately by a comprehensive campaign of public information directed to the public at large and minorities in particular. Field experience as recounted by UNHCR and OSCE staff, clearly underlines that property restitution continues to be in the forefront of the minds of minorities, who frequently seek clarification as to the methods and form that this will take

Employment

Access to gainful employment at acceptable rates of remuneration will be vital to ensuring a sustainable future for minorities. Freedom of movement is again of relevance. Minorities restricted to their own homes or to very limited geographical areas obviously have little prospect of holding down a job and being able to support their families.

Within the UNMIK structure and the wider humanitarian framework concerted efforts have been made to encourage employment of minorities. Institutional actors and the NGOs by the very nature of their work with minorities, have hired a certain number of translators, assistants and technical personnel drawn from within the groups that they work with. However, many of these opportunities are limited to working within a mono-ethnic environment and can even require security presence to guarantee that they can be carried out. This is the case even for minority staff engaged by the major institutions with cases of intimidation and harassment at the hands of other local staff of differing ethnicity being recorded. If this can occur within institutions actively working to promote ethnic tolerance, it does not bode well for how minorities would fare in the more open commercial employment market.

With respect to employment within the public sector UNMIK takes the lead in ensuring that minorities are given fair access. Only limited success has been achieved so far with respect to functions such as judges and other public servants due to a combination of factors. Efforts to maintain open access for minorities within public service jobs are fraught with difficulties. On the one hand minorities are reluctant to put themselves in a position that would be a potential risk for them, working side by side with another ethnic group that they do not feel confident with. On the other hand Kosovo Albanians may block the path of minorities, through open resistance or more subtle means. While this more frequently affects non-Albanian minorities, in the particular circumstances of Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice, Kosovo Albanians have fallen victim to similar practices with the hospital and other services being dominated by Kosovo Serb staff who steadfastly refuse to countenance working with Kosovo Albanians. Despite these difficulties some gains have been made in favour of minorities in the public sector. During the reporting period for instance it was recorded that some 14 minorities had been successful in regaining their former jobs thanks to intervention on their behalf by UNHCR funded, Legal Aid and Information Centres, and support from UNMIK.

On the open job market, a determining factor is often the personal relationship between employer and employee before the conflict and the perception of the employee's behaviour during the conflict. On this basis some Kosovo Albanian employers confident of the fact that minority employees took no part in atrocities will re-employ them whereas collaborators, real or imputed, can have no hope of employment from the majority population. Those that have managed to retain or recover their jobs are few however, given the overriding concept of collective guilt that is attributed both to Kosovo Serbs and the Roma. In some cases persons have lost their jobs because they have been displaced and have no way of getting to them even if they were welcome there. In others minorities have been let go in favour of Albanians, not always on grounds of ethnic intolerance but rather to favour the interests of relatives and friends in need of a job. The continuing influx of Kosovo Albanian returnees may aggravate this situation for minorities since the limited job market will be flooded with available labour and minorities will find it increasingly hard to compete against the ties of kinship and potentially higher qualified candidates returning from abroad with more advanced skills.

Health services

Access to adequate health services is life sustaining and a major factor in determining if minorities remain where they are or seek other alternatives. Access to health care is frequently cited to UNHCR as a supporting ground in minority requests for assisted departure from the province.

The stated policy of UNMIK to maintain multi-ethnic health facilities has run into serious difficulties in many areas. Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovice sets the tone and is the headlining case. In that instance it is the Kosovo Albanian population that is effectively denied health care at the main hospital which is entirely staffed by Kosovo Serbs. During the reporting period this dispute reached such levels that UNMIK took the step of removing the UN flag from the hospital building, given that it is an institution that fails to meet the most basic standards on ethnic tolerance. Elsewhere in Kosovo while hospital facilities exist and are theoretically open to minorities the reality can be very different. Again restricted freedom of movement impedes ready access to health care as with all other services. Frequently KFOR escort is needed for patients to make it to the hospital. On arrival they may well be faced with security concerns emanating from the staff and/or visitors. This may necessitate KFOR security presence to be maintained whilst the patient remains in the hospital. This is unacceptable and it is highly questionable whether minorities can reasonably be expected to avail of healthcare in an environment where they fear for their own safety.

Kosovo Serbs are particularly vulnerable to restricted access to medical facilities and increasingly resort to KFOR military hospitals where security and impartiality of service is effectively guaranteed. While these may provide life saving services at present, it is obvious that this type of response can not be maintained in the longer term and that alternatives must be found. A specific medical facility has been installed in Gracanica/Ulpiana to attend to the needs of Kosovo Serb patients there. Kosovo Serbs often opt to leave Kosovo either temporarily or permanently in order to avail themselves of health care in other parts of FRY.

In contrast other minorities tend to enjoy much more flexibility but it has been noted in field assessments that up to 20% of identified concentrations of Roma face difficulties similar to Kosovo Serbs. The situation varies from place to place and according to the ethnicity of the patient and health providers. In some locations an effectively parallel medical system has had to be established in recognition of the fact that minorities do not enjoy the benefits of basic health care services. The realities in this regard will be illustrated in the sections by ethnic group that follow.

Education

Education is a basic right that must be available if minorities are to see a sustainable future in Kosovo. Adults who may well be able to endure the hardships of marginalisation and intimidation, blanche at the idea of their children being denied such a basic right and all that that ensues. Non-availability of education under acceptable conditions was often cited to field staff as a reason tipping the balance in favour of departure.

UNMIK envisages a multi-ethnic education system where children of different ethnic groups would share school facilities within an education system that accommodates different language streams. What this means in effect, is that students would rotate the use of classrooms according to the language stream in which they are receiving education. UNMIK recognises five languages of instruction; Albanian, Serbo-Croatian, Bosniac, Turkish and Roma. In addition there is a choice of either the Albanian or the Serb curriculum of the 1998/99 period. Use of either Latin or Cyrillic alphabet is permitted.

Many schools have been destroyed or damaged. Reconstruction efforts are underway and will continue to rehabilitate sufficient class-room space for all of Kosovo's children. Pending completion of this programme there is pressure on the available resources to be able to deliver adequately for the student's needs. Within this context minority students are particularly hard hit. In addition they have to overcome the barriers, of rejection and intolerance, to be able to avail of their right to education.

In some locations displacement and/or limited freedom of movement has made availing of regular school services impossible and parents of minority children have had to resort to ad hoc measures to ensure that their children are given at least some minimal education. Witness the establishment of "home schools" in some isolated Serb enclaves and the establishment of an informal schooling system within the Roma camp in Plemetina/Plemetine, supported by as yet unqualified education promoters, who aspire to being teachers but lack the necessary training input at present. It should be noted that Roma children have an additional hurdle to overcome, that of traditional rejection of the need for formal education. Roma parents in the Djakovica/Gjakova municipality reported that they would like their children to attend school but then conditioned this by stating that the child must want to go. The children in turn stated that they would go to school if their parents made them. The reality behind this informality about the obligation/right to education is that Roma children frequently do not attend school or do so on such an irregular basis that they fail to progress through the grades. These problems have been exacerbated by the current instability, violence and intimidation of minorities within which the right of a child to education is not necessarily considered of primacy by others.

It is often said that education is one of the best approaches in breaking the vicious circle of ethnic hatred. Such a statement is premised on the hope that the younger generations nurtured in an environment of tolerance and acceptance, within which the education system should play a very important role, can break free of the injustices and resulting prejudices that befell their parents. Kosovo is a long way from reaping any potential benefits in terms of improved inter-ethnic relations, fostered by the education system. However initiatives should be taken now if the attainment of this long term goal is to be set in motion. Incorporation into the official curriculum of what is variously referred to as tolerance, human rights or peace education merits consideration and follow up. It is consistently reported from the field that children are the perpetrators of acts of harassment and intimidation against minorities, such as stone throwing and insults and in some isolated cases even more violent behaviour. This type of behaviour on the part of young children requires a response coming from both the education and the juvenile justice system.

Ethnic Serbs

The number of Kosovo Serbs remaining in Pristina/Prishtina City is estimated to stand at approximately 700 to 800, as compared with some 20,000 estimated by UNHCR during 1998, dropping to an estimate of 5,000 in late July at the time of the preliminary assessment and falling further to 1,000-2,000 by the time of the second assessment in September. It is worth noting that the current estimate represents an increase over the 400 to 600 estimate cited in early November. This is less attributable to return than to the fact that KFOR and other actors have improved their mechanisms for communication with and support to the Kosovo Serb community and have consequently identified more persons and revised population estimates accordingly. KFOR have noted a gradual decline in the number of Kosovo Serbs requesting security escort to depart the city permanently.

The situation for Kosovo Serbs remaining in Pristina/Prishtina continues to be precarious. They continue to bear the brunt of verbal harassment and stone throwing often at the hands of children. In many cases they are terrorised to leave their homes and rely on deliveries of foodstuffs and other essential items from UNHCR and other agencies. KFOR continue to provide security to Kosovo Serbs concentrated in various locations around town. Static guard arrangements are subject to ongoing review and adaptation by KFOR in order to provide maximum security in the most flexible manner possible. KFOR with UNHCR support also provides door and window repairs and re-enforcement to Kosovo Serb homes which have come under attack. Over the holiday period KFOR conducted repeat visits to all Kosovo Serb households included on their beat, not only for security reasons but also for reassurance and morale boosting. Healthcare is supported by periodic house calls supported by a medical team from the Centre for Peace and Tolerance (CPT, a Belgrade Serb NGO). CPT premises were relocated during the reporting period to maximise their own security and to facilitate improved security for their beneficiaries. More serious medical needs involving recourse to Pristina/Prishtina hospital are a matter of concern since security escorts are required and safety and treatment at the hospital have been questioned where minority patients are concerned. Rumours persist of insecurity for minority patients in the hospital and one Kosovo Serb nurse reported having received death threats. While many Kosovo Serbs remaining within the city are the old and the infirm, there are also families with children present. However these families report serious difficulties in securing education for their children, a factor which would ultimately cause them to leave. KFOR have been providing security escort to a communal bus taking children to school in a nearby Kosovo Serb village.

The circumstances surrounding the death of a Kosovo Serb university professor and the serious wounding of his wife and mother-in-law in the aftermath of Albanian Flag Day celebrations, November 28th, left the Kosovo Serb community particularly shaken. Having remained at home all day, the family was obliged to venture out in the early hours of the morning, in an attempt to seek medical assistance for the mother-in-law , apparently suffering from stress and tension as a result of a long day of firecrackers and gunfire. Having become entangled in the midst of a crowd the professor was dragged from his car, severely beaten and shot. The two women were badly beaten before UNMIK Police and KFOR could gain control of the situation. Initially no witnesses came forward in this case despite the presence of a very large crowd of onlookers and only after intensive efforts on the part of KFOR and UNMIK Police, was a suspected accomplice to this shocking crime, arrested. The suspect later escaped from a KFOR detention facility.

Despite dramatic limitations on their quality of life many of the remaining Kosovo Serbs have expressed their determination to stay in Pristina/Prishtina, some stating that they have lived here all their lives and that they have neither the resources nor the motivation to start anew elsewhere. According to CPT estimates, of 140 Kosovo Serb families remaining within the city and known to them, some 20% will simply leave while another 20% may be successful in selling their properties. CPT complain that there are many Kosovo Serbs within the city limits who are not benefiting from KFOR protection. In contrast a snapshot survey by another actor covering 37 Kosovo Serb homes in early December revealed that 70% would like to stay, 14% intend to leave in the near future and 64% have friends nearby or elsewhere in the city. On the more negative side it also revealed that 81% never leave their homes, 86% have been subjected to some form of intimidation, 63% of which is carried out by children and teenagers, 69% of intimidation is low-level but of the serious attacks 77% involved violence. More than 50% of recent incidents cited in this brief study had occurred up to a month previously giving some indication that harassment can be contained with increased KFOR and UNMIK Police deployment on the streets. The deployment of specific human rights officers in UNMIK Police stations city-wide was noted as a positive step towards improving the protection of minorities.

In the greater Pristina/Prishtina municipality, it is estimated, often by the Kosovo Serb communities themselves, that somewhere between 12 to 15,000 Kosovo Serbs remain in a number of villages. These include some ethnically mixed Albanian/Serb villages: Devet Jugovica/Nente Jugoviq, where the Kosovo Serb population is reported to have been reduced with houses being sold to Kosovo Albanians; Kisnica, where the situation has deteriorated since the last report with increased attacks and a general lack of security leading to the departure of up to 20 families in one month. Children are bussed to school in Gracanica/Ulpiana and it is reported that some departing families are relocating there permanently since it is perceived as a more secure location; and Lebane where MDM France reported in mid November that some 34 elderly Kosovo Serbs, some with chronic diseases did not manage to see a doctor since June. In addition Kosovo Serbs are also to be found in several exclusively Kosovo Serb or mixed Serb/Roma villages. Laplje Selo/Fshati Llap has an estimated 1,400 Kosovo Serb residents, and 150 internally displaced persons (IDPs) reportedly all Kosovo Serb whereas previously Roma were also noted here. The prevailing security situation is poor with many people not daring to venture far from their homes fearing opportunistic attacks from the main road nearby. Medical services are provided by NGOs through periodic visits but these are limited. Emergencies are referred to the KFOR hospital in Kosovo Polije/Fushe Kosove from where patients are sometimes referred on to Nis for longer term treatment. Despite the current difficulties residents expressed their hope, perhaps over optimistically, that others would return in the spring. Preoce/Peroc continues to house about 750 Kosovo Serbs and an apparently increased number of Roma. The situation here has been calm with the exception of an intra-community dispute over the burial of a Roma woman which the Kosovo Serbs objected to. Caglavica/Cagllavice has an estimated 2,000 Kosovo Serbs and a small number of Roma. Gracanica/Ulpiana has somewhere between 4,,000 to 5,000 Kosovo Serbs including 150 IDPs, and a small number of Roma. Deriving strength from numbers the Kosovo Serbs have stoned passing buses carrying Kosovo Albanians. This led to a conflict on December 21st when 200 Kosovo Serbs protested at a perceived "arbitrary arrest" which in fact amounted to no more than a stone throwing child being delivered to his parents by UNMIK Police. Kosovo Serbs here complain of limited health care and access to employment. There is a health house which will be supplemented by a general clinic being build by MDM Greece. ICRC has also provided additional services here. December witnessed an increase in the number of Kosovo Serb IDPs visiting family and friends, availing of commercial bus links with Nis and Belgrade. These buses are escorted by KFOR but are regularly stoned nonetheless, when transiting Kosovo Albanian areas en route. The visitors cite harsh economic conditions in Serbia but generally conclude that the ongoing security incidents in Kosovo are not conducive to their return at this stage.

Only two Kosovo Serb women were recorded as remaining in Podujevo/Podujeve town under 24-hour KFOR guard. It is not anticipated that Kosovo Serbs would return to the surrounding villages in the foreseeable future, with the possible exception of effecting visits to Sekiraca/Sekirace which also has around the clock KFOR presence.

In Obilic/Obiliq Municipality, there are still Kosovo Serbs living in the villages of Babin Most/Babimoc, Plemetina/Plemetine, Crkvena Vodica/Palaj, Milosevo and in the town of Obilic itself. Total population figures are estimated to be down from the 3,600 previously reported in September. It was difficult to confirm figures over the holiday period as there was some evidence of Kosovo Serbs returning to visit family and/or assess their property but not remaining. In Obilic town itself the population appears to have stabilised at or around 1,000 after a prolonged period of departures. News of the availability of schooling for Kosovo Serb children prompted some small scale return in early January. The general security situation fluctuated through the early winter months with periods of calm disrupted by incidents of arson, grenade attacks and assaults on Kosovo Serbs. The town is dominated by the two power stations, previously a major employer, but with an entirely Kosovo Albanian staff now in place Kosovo Serbs are facing serious problems vis a vis employment and economic self sustainability.

Babin Most/Babimoc houses 860 Kosovo Serbs living alongside but separated from Kosovo Albanians. The village is relatively isolated and overall security has been calm but conflicts have arisen over Kosovo Albanians purchasing Kosovo Serb property, which is strongly opposed by the Kosovo Albanian community. Plemetina/Plemetine is a predominantly Kosovo Serb village (approx. 1,000) which also houses a sizeable population of Roma. Kosovo Serbs from elsewhere have migrated towards Plemetina/Plemetine attracted by the relative security offered. The ongoing question of a separate Serb school has been a point of conflict. Crkvena Vodica/Palaj also has a mixed population with 381 Kosovo Serbs (including the neighbouring hamlet of Janina Voda). Freedom of movement is limited both within the village and further afield. Verbal intimidation and harassment is commonplace with no serious incidents since early autumn. The Kosovo Serb population in Milosevo remains drastically reduced from pre-conflict levels, the location of the village along side the main road leaving it particularly prone to opportunistic drive by shootings. Fortunately these have not resulted in deaths but leave the population in a state of constant fear. Empty Kosovo Serb houses have been systematically looted in a way that suggests a high degree of organisation.

In Kosovo Polje/Fushe Kosove Municipality, numbers appear to have dropped to approximately 3,500 to 4,000, spread out between the town and the villages of Kuzmin, Batusa, Ugljare/Uglare and Bresje. There has been a wave of departures from Kosovo Polje/Fushe Kosove town during the past two months. Around 130 Kosovo Serb houses have reportedly already been sold and an estimated 60% of remaining houses are for sale. Reports persist about attempted evictions but at a decreased level than previously. Arsons are down from a high of two to three a day in September to a total of eight in November, seven in December and only one reported in January, perhaps because there is now more interest in occupying properties rather than destroying them. Departing Kosovo Serbs tend to be those who established residence in the area over the past 10 to 15 years, leaving behind those who have lived there for generations. In one neighbourhood CPT noted a reduction from ten to two Kosovo Serb families over the space of two weeks. A significant number of elderly Kosovo Serbs remain, living alone after other family members have departed for Serbia. Relying on pensions paid from Serbia they have found it difficult to cope with local shops refusing to accept Yugoslav Dinars or refusing outright to serve Kosovo Serbs. A recurring problem has been the high incidence of harassment, stone throwing and beating of elderly Kosovo Serbs, often at the hands of school children. In one incident on December 27th a 65 year old woman, on her way to the Yugoslav Red Cross (YRC) to collect assistance, reported being beaten to the ground by a 10 year old boy outside the school. While on the ground the woman was spat on by some small girls. In separate incidents two railroad workers were abducted and killed during the course of November. The mutilated body of one victim was found on November 8th in a forested area in Srbrica/Skendaraj municipality. The second victim died of chest wounds after being shot with two 9mm rounds on November 19th. The fact that both victims were railway workers prompted local fears of targeting in revenge for Kosovo Albanians having been dismissed from railway jobs. Neither case has been resolved and in general Kosovo Serbs complain that criminals even when caught are being released after 72 hours.