Saving lives at the river's edge

Saving lives at the river's edge

Jean de Dieu, 24 years old, is wrapped in a traditional cloth, or pagne, that grows redder by the minute. Bleeding from his right side, he has just arrived at the health centre in Dula, a town with one intersection on the northern border of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). His wife and brothers carry him in as I am speaking with a nurse about refugees arriving from CAR, the Central African Republic. Refugees like Jean.

"This morning he went to the market to sell a pig," his brother Antoine, 57, explains. "All of a sudden they arrived. They accused him of being an anti-Balaka and they shot at him." His body shaking, Antoine appears to be in shock himself.

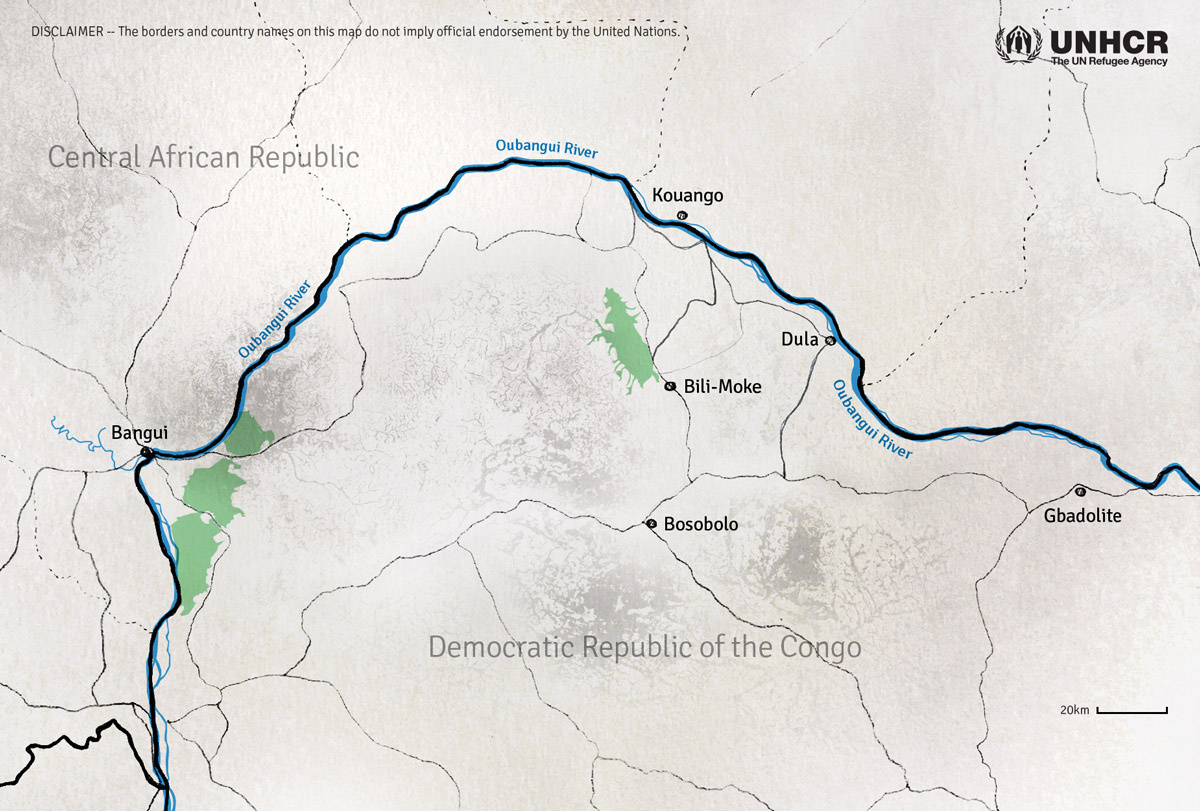

Jean's family comes from a village in CAR's Kouango district, where mounting violence since December has forced many residents to flee. They initially sought shelter on one of the islands in the Oubangui River, which forms the border between CAR and the DRC. Jean, a shepherd, sometimes dared to return home to check on his livestock.

"I was with my husband this morning," says Grace, his 26-year-old wife. She describes how they crossed the river to CAR and how Jean left her at a woman's house to take a coffee, while he went to the market.

"The moment I was shot I fell. I wanted to sleep in the grass, but I said to myself that I had to look for my older brothers."

"I heard the gunshot," she says. She thought it was a bicycle tire exploding. "Someone told me that it was my husband who was shot. When I heard the news, I started crying. I went to look for him, and we carried him to the river to take a pirogue to cross" into the DRC.

Jean, wincing with pain, recalls the incident clearly: "They came suddenly. I saluted them. They were three. The third person refused to greet me. They asked who I am. The one who refused to salute me told me to stand in front of him. He directed his gun in my direction and shot. The moment I was shot I fell. I wanted to sleep in the grass, but I said to myself that I had to look for my older brothers. I called my brother to transport me on the other side."

Now, in the improvised operating room, a health worker injects Jean in his side with a local anaesthetic and begins operating in an effort to locate and safely remove the bullet.

After nearly an hour, the diagnosis comes. The medical team has not been able to find the bullet, but found that, in addition to the wound, Jean has a broken rib that puts his life in danger.

Robert Anunu, a UNHCR doctor who has accompanied me here, says the health centre does not have the capacity to save him. Jean must be evacuated. "He has to be transferred to a hospital in Bili, or in Bosobolo, and we need an ambulance."

Bili is 75 kilometres away. Bosobolo is 100, but the road is better. The medical team makes its decision, and we moments later we are laying a sleeping mat in the back of one of our vehicles, loading in some emergency medical supplies and asking a nurse to accompany Jean on his journey to the hospital in Bosobolo.

I have come here to Dula, over 250 kilometres upriver from Bangui, as the leader of a five-day interagency mission to assess the needs of newly arrived refugees from CAR and plan the humanitarian response. In recent weeks at least 10,000 people have crossed into this part of the DRC – and possibly two or three times that many, according to government reports. With me are aid workers from World Food Programme, the DRC's National Commission for Refugees and three NGO partners.

We find that Jean de Dieu's situation is not unique. The following day our team has to evacuate two more refugees – sisters, age 30 and 14, who were struck by gunfire while fleeing an attack in CAR.

"There were troubles with the Sélékas where we lived," says Justine, the older of the two, from her bed in Bili's hospital. They fled to the bush two months ago, she explains, hoping to stop first to collect their coffee harvest before crossing to the DRC. But their luck ran out. "The Sélékas followed us. They shot me. The bullet went through my leg and touched my sister while we were fleeing."

"We saw people falling under the gunshots. Four people died. For us, we were only injured and we continued to flee to cross the river."

Her father, Kasmir, 50, describes what he saw: "It was very early. We were sleeping. It was at 5 a.m. We heard gunshots. We did not know what was going on. While fleeing, we saw people falling under the gunshots. Four people died. For us, we were only injured and we continued to flee to cross the river."

The bullet entered the back of Justine's leg, shattered her tibia and came out the other side. "There is a large wound and we have to intervene quickly," says Dr. Anunu, who helped us evacuate the sisters from Dula to Bili. "Otherwise there is a risk of amputation."

Nadine, Justine's 14-year-old sister, was also shot. The bullet remains lodged in her knee, putting her lower leg at risk of paralysis.

"She is very young," says Dr. Anunu. "We have to do everything we can to save her knee."

The hospital in Bili also lacks the capacity to treat Justine effectively, so she must be evacuated again. Again we convert one of our vehicles into an ambulance, this time to evacuate the two sisters to a hospital in Gbadolite, the main town in the region, and from there by airplane to the capital, Kinshasa. It is their only chance to be able to walk again.

This story was also published in The Guardian.