Help us quench the thirst for home, say Somaliland refugees

Help us quench the thirst for home, say Somaliland refugees

HARGEISA, North-west Somalia, March 22 (UNHCR) - It's so excruciatingly hot in summer in the Zeila district on the Gulf of Aden that, as one old-timer says, "when a bird flies from one tree to another, he will die before reaching the next tree."

There's even a 180-km stretch known as The Plain of Death ("Gegriyaad" in Somali) because of the number of drivers who perish of thirst there every year when their trucks or cars break down on the way to Djibouti.

So after Zeila's only sources of water - five boreholes - were destroyed during the civil war, there was no way Somali refugees would return to the region, where the mercury climbs to over 50 degrees Celsius between June and September.

The local nomadic people "spend most of their time fetching water; it's their main task," says Abdirashid Deria Farah, a water engineer with UNHCR in Hargeisa, the capital of the self-declared independent (but unrecognized) state of Somaliland, known also as North-west Somalia.

But now refugees are finally returning to Zeila because in recent years, UNHCR has re-drilled and re-equipped four boreholes in the region, in cooperation with UN and non-governmental organisation partners.

Even with the four boreholes, nomadic herders spend three or four days travelling in each direction to fetch water for their families and their animals, transporting the water to their homes on donkey- and camel-back.

In areas where it is technically feasible, UNHCR has also dug shallow wells for villages and farmers. "It's an extraordinarily harsh environment," says Abdirashid. "We are doing what we can to make it more liveable."

Somaliland is populated almost entirely by people who once had to flee their homes during conflict, many crossing international borders to become refugees. After 1991, when the regime of Siad Barre collapsed and Somaliland declared its independence, Somalilanders began coming home on their own. Since 1997, UNHCR has been helping refugees return from camps in Djibouti and Ethiopia, as well as further afield.

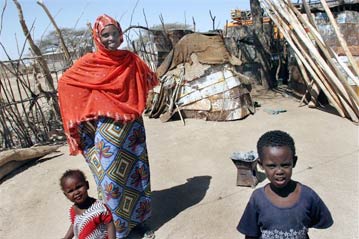

An estimated 700,000 refugees have returned to Somaliland, a place where nearly half the population lives on less than US$1 a day. Returnees are in an even worse situation; one year after their return, 90 percent do not have a regular source of income.

While Somaliland welcomes the return of refugees - who, in many cases, are helping rebuild the region - it has no money to provide necessary services to assure that their return is permanent.

"Somaliland is caught in a bind," says Simone Wolken, UNHCR's Representative in Somalia. "Because it is not recognized by any country in the world, it does not get any bilateral aid. The only money available for reconstruction and development has to come from the UN and NGOs."

Between 1993 and November 2004, UNHCR carried out 677 projects - ranging from building latrines so girls could attend school to teaching men and women how to keep bees and sell honey to support themselves - that benefit an estimated two to three million people in Somaliland. The projects represent an investment of more than $23 million by UNHCR.

"These community-based reintegration programmes, including 58 in Somaliland in 2004 alone, have helped to improve the access of vulnerable populations to the basic services of water, health, education and sanitation and to improve their livelihoods through local economic development," said Wolken.

"While the number of projects may appear high, they only met a small fraction of the needs," she added. The UN and NGOs working in Somalia have appealed for $164 million for this year's projects, of which $6.6 million would go to UNHCR; in recent years, the requests have not been fully funded, which limits the ability of the UN to adequately help Somalis.

In an area where peace is still fragile, "we have to strengthen it through development," Wolken adds, "and make sure that these people never have to become refugees again."

In Aisha refugee camp in eastern Ethiopia, one of the last camps in what was once the world's largest refugee-hosting area, the last Somalilanders are going home.

What they value above all else is the peace that now reigns at home, but they are worried about the harsh life they will face.

Roble Hadi Kahin, the 50-year-old chairman of the refugee committee, and father of eight children, is worried that his younger ones will not be able to continue their education once they go back home in a few weeks.

So he has a challenge for world leaders: "The area I am returning to is an area without water, without health facilities, without education, but we are ready to return. Has the world any idea of helping us?"

By Kitty McKinsey in Somaliland and Aisha camp, Somalia