A childhood of rape and exploitation ends mercifully with a new life in Canada

A childhood of rape and exploitation ends mercifully with a new life in Canada

DAMASCUS, Syria, Dec. 31 (UNHCR) - For any refugee, the chance to begin a new life in Canada is a coveted prize. But for Hiba,* wearing a huge smile as she approaches the departure gate at Damascus airport, the plane she's about to board means leaving behind the unimaginable horror of rape, exploitation, human trafficking and prison - a lifetime of torment lived by the age of 17.

Hiba's fate seemed to have been sealed when her mother left her with her father in Baghdad when she was just seven. When she was 15, he forced her into a mutaa marriage, or temporary marriage, with a cousin.

Under this traditional local custom, Hiba was informally married to her cousin for 48 hours, but he abandoned her after satisfying his lust. Her father refused to take her back.

Instead, he persuaded her they could find her mother in Syria, and set out to meet her. At the Iraqi-Syrian border, Hiba went to the restroom, only to discover her father was gone when she came out. Little did she know her father had sold her to a stranger. Hiba's nightmare was just beginning.

Trapped in a country where she knew no one, Hiba had no choice but to put her trust in the man who claimed he would protect her. Instead he brought her other men, who raped her in turn. A few days later she was taken to a club in Damascus, taught to belly dance provocatively to attract customers' attention, and was forced into sex work for nearly two years.

When she became pregnant, though, Hiba's captors abandoned her, leaving her on the streets to fend for herself. She was soon found by local social workers and put into the Damascus rehabilitation centre for minors. Hiba felt safe for the first time in years and was comforted by the social workers at the centre. It was clear that this could not become home though.

"When I first arrived, I was scared and terrified by what was going to happen to me next," Hiba said. "Soon, I was reassured by the presence of other girls in similar situations. We became sisters, they replaced my family. I also realized I was not an isolated case. A lot of girls need help and assistance."

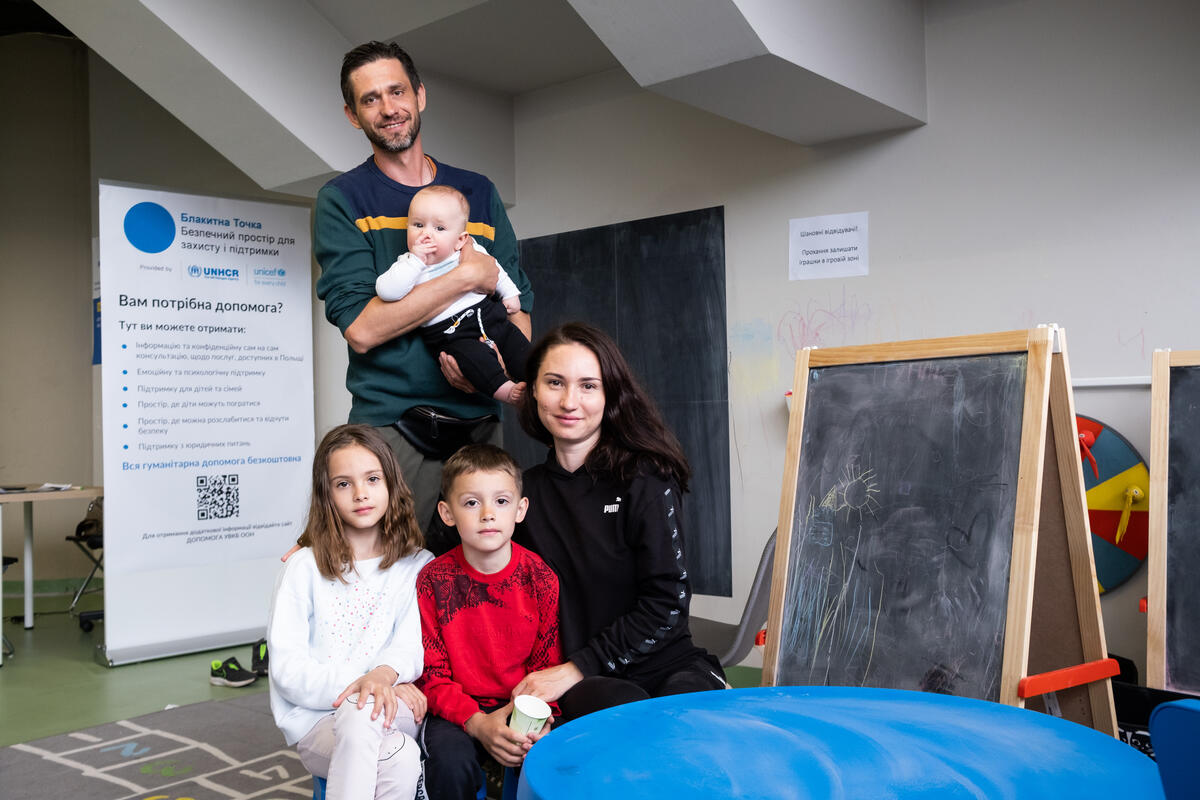

Hiba remained in the centre for several weeks before being identified by a Syrian social worker who reported her plight to the UNHCR office in Damascus, which submitted her case urgently for resettlement. Canada answered the emergency call.

UNHCR protection officers say that in many asylum countries, an increasing number of Iraqi women and girls are being forced into sex work against their will, or are turning to it in desperation for economic reasons.

Aseer Al Madaien, UNHCR Protection Officer in Damascus, says UNHCR works hard to find women like Hiba who are being exploited. "With the support of Syrian institutions, we are constantly trying to increase our efforts in terms of prevention," says Al Madaien. "We are counting on the support of local partners, government offices and NGOs specifically targeting women at risk."

On the last day of 2008, the Syrian Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour and the International Organization for Migration announced the establishment of the first shelter for victims of trafficking like Hiba. It aims to provide a safe haven for survivors of trafficking, with Iraqi women and their children being one of the target groups for assistance. This project, which also involves other UN agencies and local NGOs aims to build referral networks for survivors and it is hoped that other shelters will be established in the future.

According to the Syrian government, there are around 1.2 million Iraqi refugees in Syria, of whom more than 220,000 are registered with the UN refugee agency. Of these, more than 2,800 are women at risk. In 2007, UNHCR in Syria requested resettlement countries to accept 945 women and children at risk, but would like to find places in third countries for even more.

For Hiba, the future is finally looking brighter. Living safely in Canada now with a foster family, she recently gave birth to a baby girl whom she named Zaman, which means "time". Perhaps Hiba was thinking of the time ahead of her - time to recover, time to heal and time to start a new life

* Name changed for protection reasons

By Dalia al-Achi in Damascus, Syria