Stronger together, thanks to a unified approach to refugee education

Stronger together, thanks to a unified approach to refugee education

After a heart-stopping phone call at work alerting him that his small child had been mowed over by a cyclist, Justin Mbulani was relieved to find his little one recovering comfortably at home.

But even after he’d inspected each cut and bruise, a feeling of uneasiness remained.

Such incidents had become too common in the Makpandu refugee settlement in South Sudan’s Western Equatoria State, where Justin, a Congolese refugee, lived side-by-side with local South Sudanese and refugees from the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan.

In two years, at least five children had been involved in motorbike accidents while their parents were away working. On three occasions, children playing with leftover breakfast coals accidentally set fire to their own homes.

“Let’s open our own nursery school.”

Something had to be done, Justin resolved. So, he gathered his neighbours.

“Let’s open our own nursery school,” they decided.

Founding a nursery school is just one example of how these parents, in a sprawling rural community of mud huts and maize fields, are working together to heal the wounds of conflict and secure a better future for their families through education.

Over the last few years, they have built classrooms to reduce crowding at Makpandu’s primary and secondary schools and founded a community-based organization – the Youth Association for Peace and Development – to coordinate volunteer-run computer skills and English courses, establish football and volleyball leagues and more.

When South Sudan shuttered schools for nearly six months in 2020, from late March until October due to the coronavirus prevention measures, parents stepped up to support their children, who had to continue studying from home, without laptops or high-speed internet.

Justin has always been resourceful. After watching his next-door neighbour murdered and three young nephews abducted by armed militants, he fled from his village, pushing his children all the way to South Sudan on a bicycle in 2010.

“You don’t leave your mind behind when you run to another country,” says Justin, “You bring your ability with you and use it to improve your circumstances wherever you are.”

The nursery school operates out of a couple of dilapidated thatched-roof classrooms previously occupied by a defunct Christian mission school. More than 400 children, including 190 South Sudanese children, are enrolled in classes that meet four times per week. Seven parents, three of them certified out-of-work teachers, volunteer to lead the lessons, using the South Sudanese national curriculum.

Joyce Archangelo, a South Sudanese mother of three, was thrilled to learn the school was open to all because preschool slots at the Christian mission school had been reserved for refugees.

During a French lesson in early March, her four-year-old daughter Helen was among the most vocal students, exuberantly bouncing on her wooden bench as she called out the names of various items of clothing.

“Every parent has a duty to educate their children.”

“Un chapeau! Hat!” she shouted. “Un robe! Dress!”

Joyce volunteers at the nursery school in her spare time and is an active member of the parent-teacher association at Makpandu’s primary and secondary schools.

“Every parent has a duty to educate their children, unless he or she is not serious about the future of the community,” she adds.

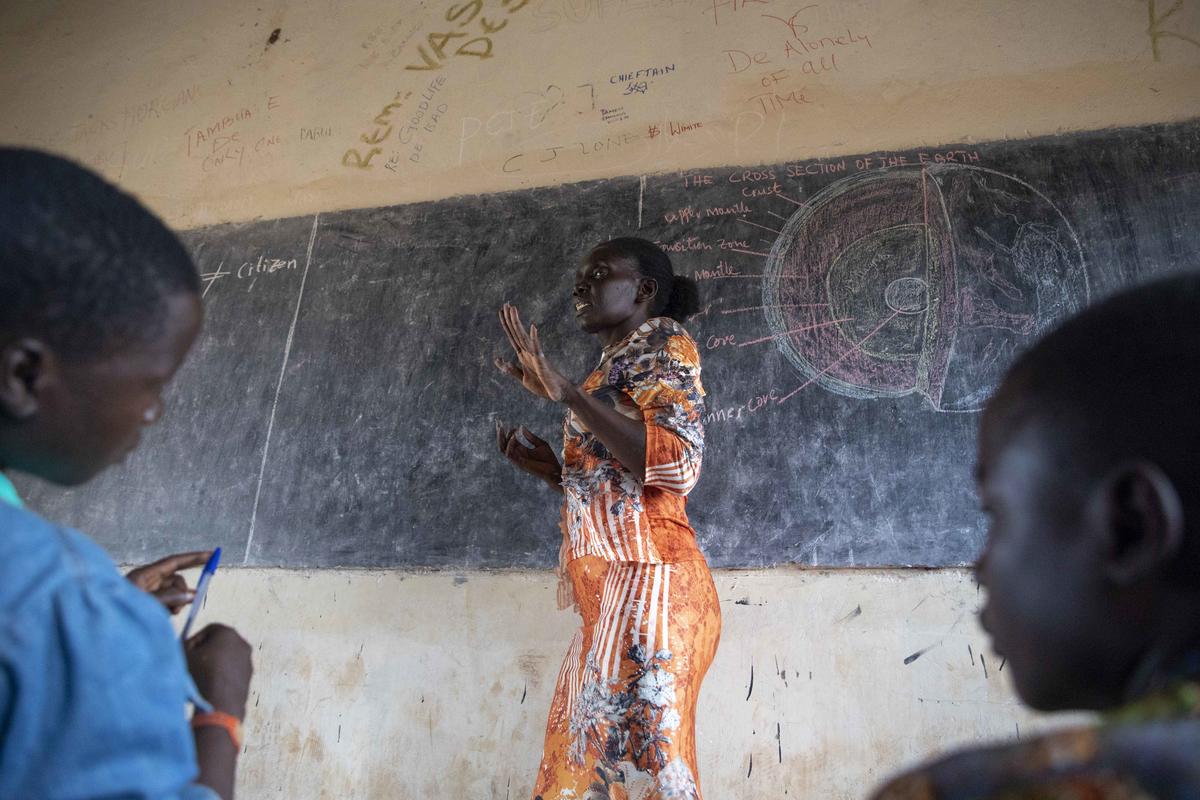

Research shows that family engagement in schools leads to higher test scores, better social skills and improved behaviour. In Makpandu, the combination of a strong parent-teacher association and an energetic community has been instrumental in turning out some of South Sudan’s best students, says Nur Issak Kassim, the head of UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency’s Yambio field office.

The settlement’s secondary school has been ranked among South Sudan’s top ten schools for three years in a row. Last year, it produced seven out of ten of the country’s highest performing students. Its reputation is so strong that more and more South Sudanese parents from other parts of Western Equatoria are sending their children to board with friends or relatives near the settlement so they can enroll.

“Familial support is particularly crucial in Makpandu,” says UNHCR’s Nur, where many residents have been forced to flee their homes multiple times. Decades of insecurity across the region have derailed studies, destroyed schools and disrupted the development of educational institutions, resulting in some of the world’s highest out-of-school and adult illiteracy rates.

“We need all hands on deck here, especially parents,” adds Nur.

Parent groups maintain a close relationship with UNHCR, which acts as an accelerator for their initiatives.

When class sizes in Makpandu’s schools ballooned to more than 100 in February, parents came to UNHCR with a proposal to build a few temporary classrooms. More than 125 families contributed a half-day’s wage to purchase hardware. Parents negotiated with the owners of a local teak plantation for permission to scavenge for scrap wood. They only requested UNHCR to help transport the lumber back to Makpandu.

At the preschool, UNHCR donated school supplies and solar lamps and facilitated efforts to secure land from the government for a new classroom complex. Volunteers who teach tech courses use UNHCR-provided laptops and some volunteer English teachers are graduates of UNHCR courses.

While schools were closed to mitigate the risk of spreading COVID-19, UNHCR relied on the parent-teacher association to maintain close communication with students — support that will remain essential as South Sudan continues to reopen schools in phases over the next six months. The government requires a number of COVID-19 prevention measures to be put in place, including providing personal protective equipment, disinfecting schools, and reducing class sizes to allow for physical distancing.

“We are teaching our children to live peacefully and come together to find solutions when they have problems.”

“We are teaching our children to live peacefully and come together to find solutions when they have problems,” says Hozana Fuore, 39, a Congolese refugee and mother of 13 who, alongside Joyce, was part of the classroom construction project.

Working side by side for their children has bolstered peace and understanding across communities, she says. Tension over resources like firewood and water have eased as the communities have grown closer. Many refugee families have even opened up their homes to accommodate out-of-town South Sudanese students, so they can access Makpandu’s schools.

The children are learning from their parents’ example.

At the nursery school, the five-to-six-year-old class wrapped their arms around their neighbours’ shoulders.

“Thank you, Papa! Thank you, Mama!” they sang. “For loving South Sudan and supporting South Sudan!”

They swayed back and forth – South Sudanese and refugees – as one.