By Ibrahima Sarr, Theresa Beltramo, and Jedediah Fix

At the start of 2022, Uganda was already hosting over 1.5 million refugees, making it the largest refugee hosting country in Africa. By early September UNHCR confirms that nearly another 100,000 refugees have recently arrived since the start of the year from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo and the humanitarian response in Uganda is being stretched to a breaking point.

Our recent work examining refugee’s socio-economic experience in Uganda highlights that refugees in Uganda face significant employment gaps that are sticky even after 10 years on, despite the progressive policy environment providing land and freedom of movement and work. In order to ensure refugees (both new and old arrivals) can sustain their families and contribute to the local economy, more work is needed to link refugees to the labour market.

To build the evidence base on the lived experience of refugees in Uganda, we generated a specific analysis of employment using socio-economic data that is comparable between refugees and Ugandan nationals. The insights from the data* contribute to our collective understanding of displaced populations and inform UNHCR’s efforts to guide the agenda towards inclusive solutions, a goal emphasized in the Global Compact on Refugees.

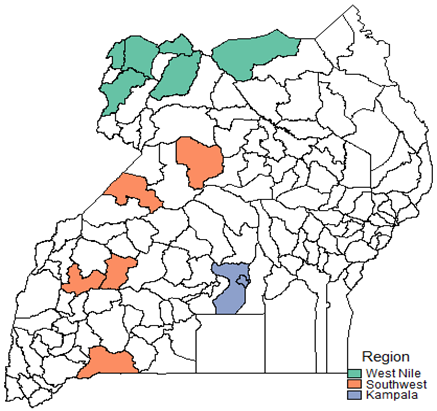

Figure 1: Sampled regions

Even in an ideal policy environment, there are fundamental challenges to economic inclusion

The Ugandan macro-economic context faced distinct challenges even before the COVID-19 pandemic caused economic upheaval. Among other factors, a massive demographic youth bulge is exerting immense pressure on the economy to accommodate about 600,000 new jobseekers per year by 2040 (Merotto, Weber, and Aterido 2018).

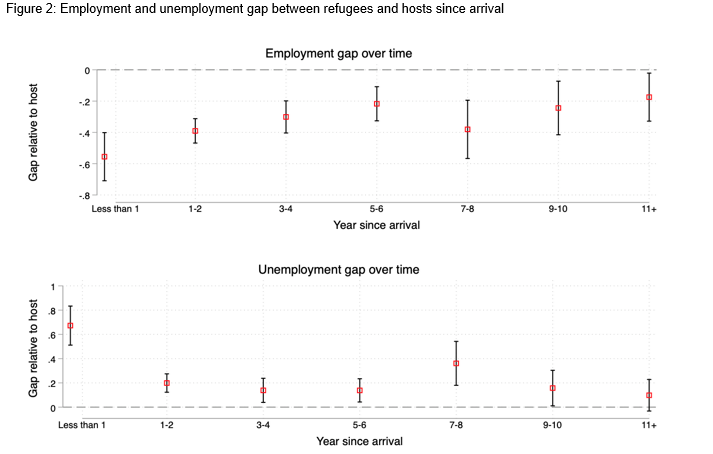

Providing support to refugees in Uganda in navigating this difficult labour market context, given their own inherent vulnerabilities, is key to enabling their resilience and economic survival. Our analysis shows that refugees in Uganda are disadvantaged along a range of employment-related outcomes compared to nationals, despite the progressive regulatory approach towards refugees. The data show a large employment rate gap of 35 percentage points between refugees and Ugandan nationals and a corresponding labour participation gap of 27 percentage points. Further, we find these disparities persist over time and start to slightly converge only after a decade after refugees’ arrival (Figure 2). But the gaps remain large – after 10 years, there remains an employment gap of 20 percentage points while the unemployment gaps become insignificant.

Even among those refugees fortunate to find work, many find the conditions do not lead to a higher standard of living. Poverty among working refugees is striking compared to nationals, with the former 1.75 times more likely to fall below the poverty line. This is largely driven by lower earnings despite the refugees having similar education and professional backgrounds as their national counterparts.

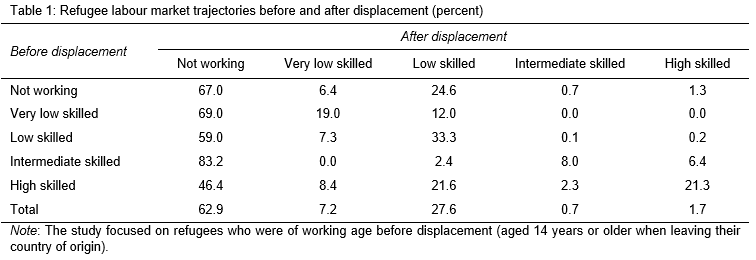

Moreover, refugees are more likely to be underemployed – especially those with higher levels of education – meaning they are not able to fully capitalize on their unique skill sets. Using measurements of skill levels before displacement, 66 percent of low-skilled refugees accepted jobs below their skills level – known as professional downgrading – compared to 85 percent of intermediate-skilled and 79 percent of high-skilled refugees (Table 1). Professional downgrading is believed to be partly due to the lack of recognition of qualifications and poor transferability of skills and professional experience (Fasani et al. 2018). On the other hand, it may result from outright discrimination from employers or the lack of information about their legal right to hire refugees (Loiacono and Vargas 2019; Chang 2018). Faced with this reality, it is unsurprising that 65 percent of refugee respondents say they would like to be engaged in the occupation they had before being displaced. But only 20 percent manage to do so.

Considering the demographic pressure exerted by the large youth population in Uganda, younger Ugandan individuals, making up nearly half of the working-age population, face significant barriers to employment. Yet younger refugees face worse odds – they are three times more likely to be unemployed than younger nationals (44 percent versus 14 percent). Similar gaps exist when comparing the employment rate of the refugee and national populations by gender. The extreme underemployment of youth refugees is likely to impede socio-economic advancement for the future generation of refugees, potentially causing further impoverishment and eroding gains.

What can be done to address the identified barriers to economic inclusion?

Despite the enabling regulatory environment in Uganda, refugees’ employment outcomes are relatively poor and undermine their socio-economic integration, prosperity, and ability to improve their wellbeing and contribute to the Ugandan economy and society.

Based on the insights on factors obstructing the socio-economic integration of refugees in Uganda, addressing them require several key policy steps. We outline the main ones here:

Assess refugees’ skills early, facilitate job matching soon after arrival, and provide upskilling training. While the employment gap between hosts and refugees narrows slightly over time, it never reaches parity. Providing skills assessment soon after refugees arrive and investing in training and labour market integration activities could help refugees get better jobs and wages sooner. Using a standardized approach to measuring skills upon registration of refugees may shorten the time needed to match refugees to labour market skills requirements. Refugees would also benefit from job search and matching programmes to overcome their lack of local knowledge and social networks. Evidence suggests such programmes are associated with positive effects on employment prospects (Battisti, Giesing, and Laurentsyeva 2019).

Recognize overseas qualifications, especially those from the region. The extensive under-employment and downgrading among refugees represent missed opportunities for the local economy as well as for the refugees, as their talents and skills are not put to productive use. Cross-border or regional accreditation standards would facilitate the movement of human capital for Ugandans and refugees. This could be particularly beneficial for Ugandans, given the demographic youth bulge and the increasingly difficult employment situation. It could also potentially improve wage equity and limit poverty for working refugees.

Increase attention linking youth to the labour market. Both hosts and refugees have difficulties finding jobs. The negative consequences of extended unemployment and inactivity in the early years of one’s career include financial hardship, lower employment, and lower long-term earnings prospects. As many young people leave school early and have no qualifications, second chance programmes could help individuals increase their formal education, obtain recognized certifications and improve their chances of finding a job. Employment training should be a combination of institution-based and on-the-job training, as evidence suggests this combination yields higher positive labour market outcomes (Fares and Puerto 2009). Additionally, the expansion and strengthening of national Technical and Vocational Education and Training programmes and accreditation to include refugees should be explored.

More investment in education and training is needed to improve labour market outcomes. Despite the returns to secondary school education, completion rates remain low for refugees. Among youth of secondary school age (between 19 and 23 years old), only 11 percent of refugees completed secondary school versus 24 percent for host communities. Measures to improve education outcomes are critically needed to strengthen the human capital potential of the refugee population. UNHCR and its partners should explore measures such as reducing school tuition, creating scholarships and programmes subsidizing secondary school fees, and providing direct cash transfers to low-income refugee families. These financial support offsets the opportunity cost of the student studying instead of working to provide for the family. For refugees who do not continue to higher levels of education, continuing their education in basic literacy, numeracy, language, and soft skills, followed by vocational training, provides them with better chances of employment.

Sensitize both refugees and potential employers on refugees’ right to work. Existing evidence indicates that just 21 percent of employers in Uganda reported knowing that refugees are allowed to move freely. Moreover, only a small minority of employers (23 percent) know that refugees have a right to work in Uganda, limiting job opportunities for refugees even further. Refugees would benefit from awareness-raising campaigns for private sector to sensitize on refugees’ right to work. It would be helpful for refugees to advocate for a review of the administrative process for issuing work permits to refugees to access employment.

*Data source. Our study relied on household data collected by the World Bank the Uganda Bureau of Statistics in 2018 in three main refugee-hosting regions: urban Kampala, the SouthWest and West Nile (Figure 1). The data covers refugee and host population. The global geopolitical environment and the risks to economic growth have been negatively impacted since 2018, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The trends in employment explored in our analysis remain relevant and are insightful for policy discussions.