Rescue at sea

Rescue at sea

Without the binoculars, it didn't look like much. Just a haze of blue and orange, bobbing gently on the horizon. Lifting the lenses to my eyes, I was able to make out more: a dilapidated boat, a sea of life vests and over 200 people packed on board.

"You will feel the impact when they arrive," the captain told me, wiping beads of sweat from his forehead as he steered our Italian military ship through the waves. "It is not something you can ever be fully prepared for. Every time is different."

Down below, a rescue team was assembling. After several days of bad weather, it would be their first exercise that week – but not the last. Indeed, before retiring for the night, the crew would pick up more than 1,000 distressed passengers from four different boats.

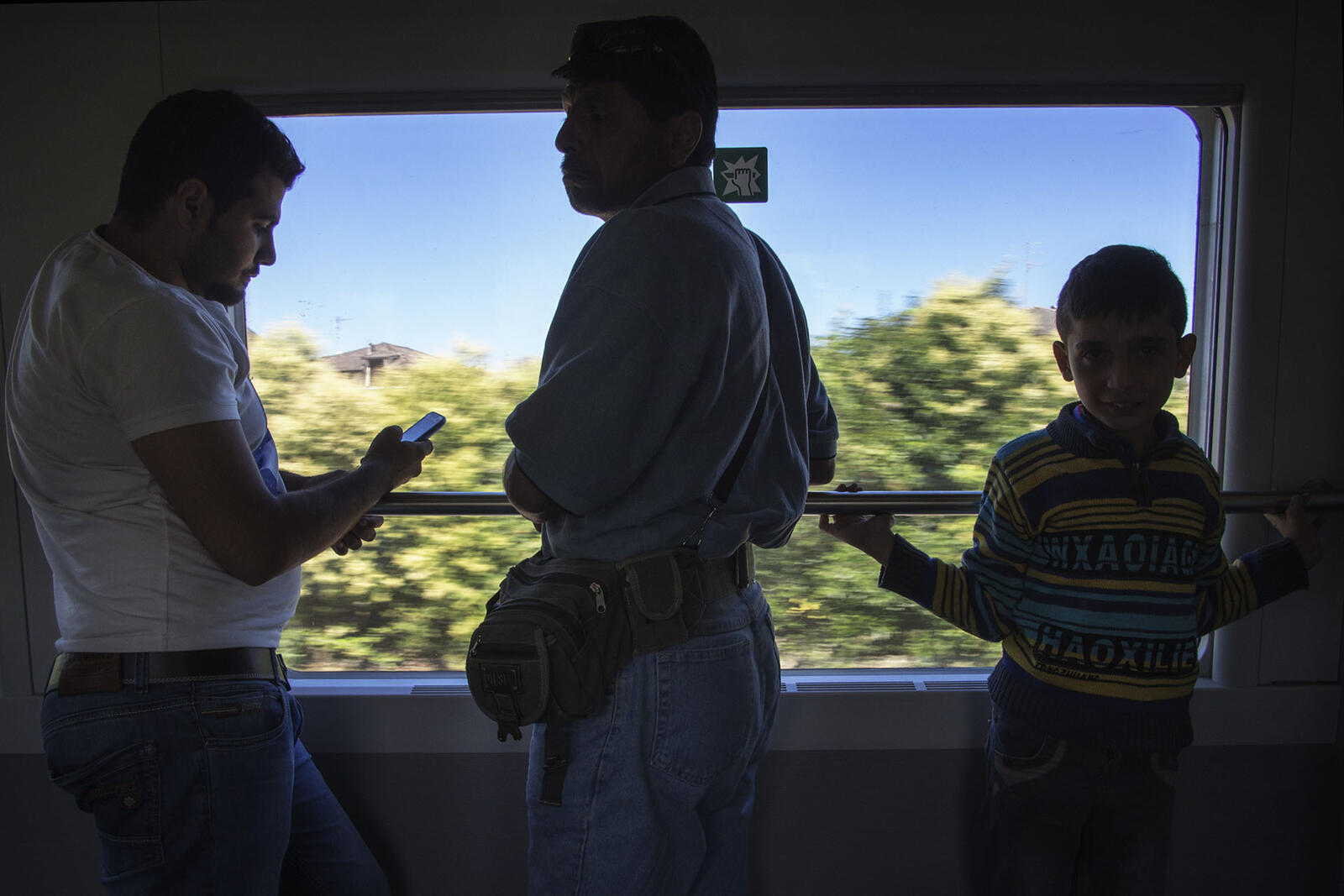

Like so many refugees before them, the desperate men, women and children at sea that day were lucky to have made it into Italian waters at all. Their 18-hour voyage on the Mediterranean was fraught with danger, and for hundreds just like them it had ended in disaster. Now, having been spotted by the San Giorgio as part of Italy's Mare Nostrum operation, all they could do was hope to be rescued.

Women, children and those in need of medical attention were first off the rickety boat – among them, young mothers. "Can my child have some milk?" asked one, gaunt and exhausted, clutching a toddler with her arms. "His feeding bottle fell into the water."

As a total of 210 people boarded, I took the lady gently by the arm and asked where she was from. Her eyes were bloodshot from the tears. "I am from the town where the revolution started," she replied, referring to Dara'a in Syria. "Now my city is gone."

In a makeshift registration area, officers processed those who had fled their homes. "I don't think I have come across people from the Central African Republic and Kashmir at the same time," remarked one marine, jotting down names and nationalities. I peered over his shoulder. Sudan. Eritrea. Pakistan. Somalia.

One weary man from Kashmir in Pakistan told us his name was Khan. At the age of 54, he had been forced into exile after military assaults created a living hell for him at home. A smuggler in Lahore promised him "a better life in the West" – the journey had cost him his life savings.

Behind Khan was 25-year-old Mamadou, who had been displaced within Mali after an uprising and coup in 2012. The marine gave up after three attempts at spelling his name. "Please write it yourself," he said, handing him the pen.

Mamadou, when I found him later in the men's section, explained to me how he had fled from Mali and eventually found his way to Libya. "I knew it is very dangerous in Libya, but I had heard about boats that take you to Italy," he said, fatigue lining his face. "I had to take the chance as I had been fleeing for over a year."

In the span of just six hours, the crew of the San Giorgio rescued 1,171 men, women and children from four boats. A sister ship, the Etna, brought another 1,023 people to safety. Many came empty-handed, others clutching a few treasured possessions. All were desperate to come aboard.

They all had reasons for risking their lives at sea. Some had fled armed conflicts back home, others escaped political and religious persecution. Some had been at risk of modern-day slavery, others were manipulated by criminal gangs.

Early the next morning I met Afwerki, who had paid €900 for his voyage at sea. The price set by the smugglers was just enough to deplete his savings, but not enough to earn him a life vest. Now 25, Afwerki had fled Eritrea several years earlier to avoid military service, but as a refugee in Ethiopia did not feel he could "live freely and safely," he told me, chewing gratefully on a roll. "I am from the wrong side of the border." He remains hopeful that in Europe his life will truly begin.

In the first half of this year, Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt took in another 500,000 Syrian refugees – bringing the regional total to nearly 3 million.

At the other end of the spectrum is Anwar, 76, who held out as long as he could before fleeing his ancestral home in Syria. "I don't know what I'm going to do," he told me, glancing at his young grandson. "After 75 years in my country we were forced to run away, me and my sons. How is that possible?"

Thurayya, from Lattakia, had also been uprooted from her home, fleeing with two sons, a husband and six other family members. Back in Syria, she had been an English teacher at an elementary school. That day, I found her sitting in a large section crammed with families. "When do you think we will reach Italy?" she asked me, in perfect English.

Others wanted to know the same – desperately seeking refuge, having travelled hundreds of miles and risked death at sea. Counting on Europe.

I hoped it wouldn't let them down.

Later, as we approached the harbour, a weight seemed to lift. There, at last, was land. For the hungry and exhausted, life was about to begin again.