Young asylum-seekers spend summer break learning German

Young asylum-seekers spend summer break learning German

“Let's go through the year,” says the teacher, gesturing encouragingly at a small Syrian boy. He puts his head on one side and gazes at her quizzically for a moment. Then the penny drops. “Januar,” he says proudly. His classmates catch on and dutifully recite the German names of the months in order.

It's August in Berlin. Most German children are outside playing in the sunshine, school firmly out of their minds over the summer break. Meanwhile, young asylum-seekers and refugees all over Germany are spending their summers sitting in classrooms, drilling German grammar rules.

“I didn't know a word of German when I got to Berlin,” said Sanas Somijara, an Afghan asylum-seeker and summer school pupil who arrived in Germany together with her family 10 months ago. “It wasn't so bad because I could already speak a bit of English. But lots of other children had it really hard because they didn't even know the [Roman] alphabet.”

Once 15-year-old Sanas and her family moved into a Berlin shelter last winter, she and her two siblings were keen to start school. Their parents applied to local authorities, and the children were assigned to so-called welcome classes. These are parallel classes run in Berlin's primary and secondary schools, designed to prepare newcomers to enter regular schooling.

Together with 13 other children from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq, Sanas took intensive language lessons and was introduced to the basics of German society and culture. “The welcome class was a lot of fun,” she said. “We had a good teacher and she always helped us. It just felt like being in a normal class really.”

Sanas' German improved so quickly that after six months she was allowed to transfer out of the welcome class and into regular ninth grade classes with her German peers. But that has not stopped her from taking the opportunity to brush up on the language during the holidays.

“I like school here. The teachers help me to read and write. It's fun playing games.”

“We've had a lot of fun here in the summer school too, making new friends, playing sport and going on outings,” she said. “Most of the time we speak German to each other, but we translate into our own languages if one of us needs it.”

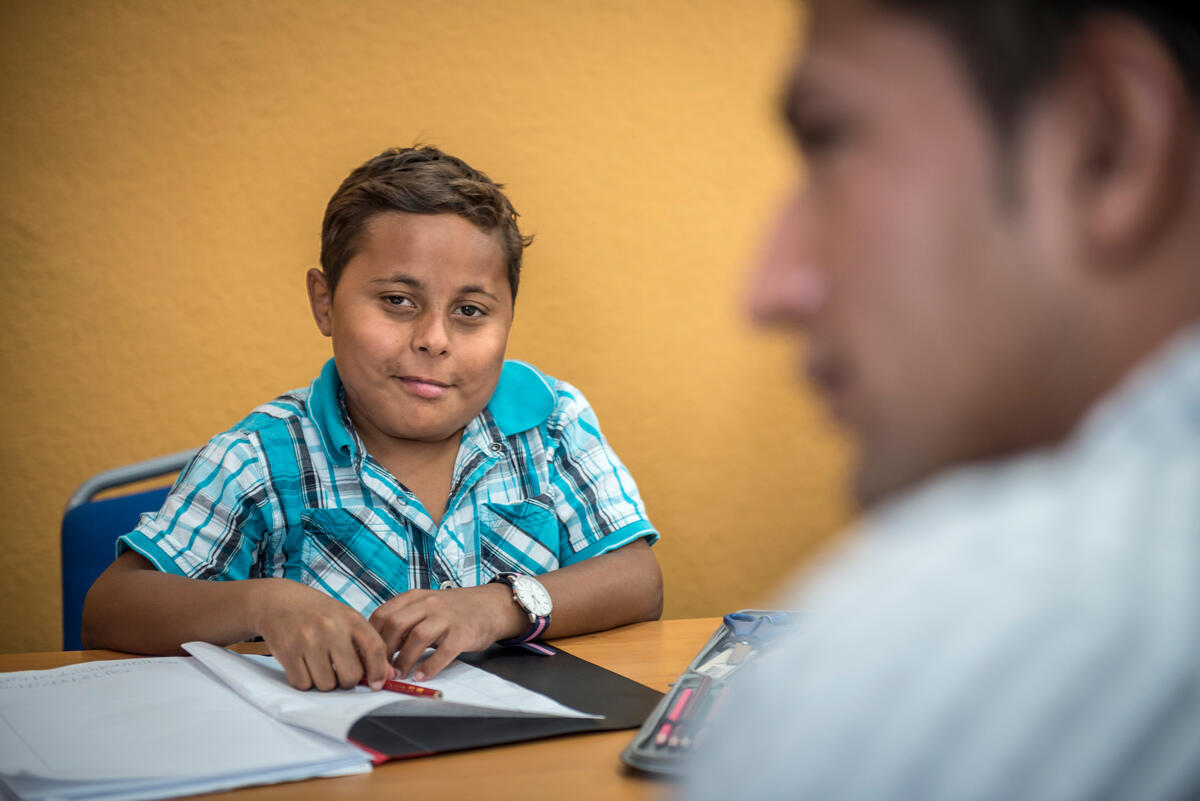

Others in Sanas' summer school class are finding the language more challenging. “German is very hard for me. It's very difficult,” said Mahmoud Jad, a 13-year-old asylum-seeker from Syria. He fled his home in Damascus with his older brother and arrived in Berlin in February. But despite the long slog, Mahmoud is enjoying learning. “I like school here. The teachers help me to read and write. It's fun playing games.”

Teachers at the Lehrreich summer school in West Berlin say making progress is harder for unaccompanied children such as Mahmoud. When term starts again in September, he will return to a welcome class until his German is good enough to join regular school. Meanwhile, extra classes at the summer school help him keep up his efforts.

“The children who join summer schools in Berlin wouldn't otherwise have the chance to learn German during the six-week holiday,” said Yvonne Hylla, program coordinator at the German Children and Youth Foundation (DKJS), the state-funded umbrella organization responsible for Berlin's refugee and asylum-seeker summer schools.

“We've had good feedback from the welcome class teachers that these children don't stagnate and forget everything over the summer, but instead make progress over the holidays,” she added.

"Germany is a very good place because I can go to school and I don't have to be afraid," says Samira Marwi, age 15, from Afganistan, who lost both her parents at a young age.

Summer schools and welcome classes help children integrate into the school system, as well as into the cities and communities that have welcomed them. Many of the approximately 1.35 million people who have been pre-registered for asylum in Germany since the beginning of 2015 are children of school age. And after three months of residence in Germany, every child has both the right and the legal obligation to attend school.

Having fled deadly conflicts in their home countries, many refugee children have not have been to school for years and carry haunting memories of war and flight. They have to learn a new language in a different cultural context, as well as make new friends and acquaint themselves with a new environment. To support teachers and pupils alike, UNHCR has published teaching materials and continues to call for integration opportunities for children and the implementation of adequate measures to secure their well-being.

“Germany is a very good place because I can go to school and I don't have to be afraid.”

“Germany is a very good place because I can go to school and I don't have to be afraid,” said Samira Marwi, an Afghan asylum-seeker and summer school pupil whose education at home was constantly disrupted by the threat of violence against schoolgirls.

During term time, 15-year-old Samira, who arrived in Berlin last November with her older brother, also attends a welcome class during term time. “My teacher says I'll have to stay on in the welcome class a bit longer, because my German isn't good enough yet,” she said.

But whether it's in a welcome class, summer school or regular school classes, Samira is just glad to be able to learn in peace. “I want to stay here, go to school and study. Then I'll become a doctor and be able to help people,” she said. Meanwhile, her classmate Sanas dreams of one day becoming a pharmacist. “The journey here to Germany was so hard,” she said. “Now we want to stay and study and make a new life, a good and beautiful life with no fear.”