Camps in north-eastern Chad running dry, warns UNHCR

Camps in north-eastern Chad running dry, warns UNHCR

Refugee women carry full jerry cans from the water taps in Iridimi camp, eastern Chad.

ABECHE, Chad, Oct 26 (UNHCR) - Water supplies are drying up for tens of thousands of Sudanese refugees in eastern Chad, warned the UN refugee agency, saying that at least one refugee camp could run out of water within two weeks.

Eastern Chad is one of the driest places on earth with a rainy season of only three months per year. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that this year's rains came late and far between, with total rainfall only about a third of normal amounts.

This arid region is home to 200,000 refugees who have fled the fighting in western Sudan's Darfur region since early 2003. Most of them live in 11 camps in eastern Chad. UNHCR and its partners, who oversee the camps, have been searching for water in the area for months, but there are fears that existing supplies in some of the camps are dwindling.

"Right from the beginning, we knew that it was virtually impossible to find enough water for 200,000 people in this region," said Dinesh Shrestha, UNHCR's senior water and sanitation officer. "It's especially hard in the north-east, which has scattered and small, localised pockets of underground water that can't last for such a huge population over a long time."

In Iridimi camp near Iriba, for example, the water table is decreasing much faster than foreseen, with the current supply likely to last for only two more weeks - despite pumping 23 hours a day. The 15,000 refugees at the camp are currently receiving only 6 litres of water per refugee per day, far below UNHCR's standard of 15 litres during an emergency operation.

Water experts who have analysed other possible sources near Iridimi say there is only a 10 to 15 percent chance of finding enough water for the 15,000 residents of the site. Even if more water is found at the site, however, it is likely to be enough for just two to three months or perhaps somewhat longer if Iridimi's population is reduced to just 5,000 refugees.

As a first measure, UNHCR has decided to begin trucking water to the camp and have started talks with the local prefect to draw water from the city of Iriba for a limited period. This, however, may exhaust the region's water supplies.

UNHCR is also looking into the possibility of moving some 7,000 refugees from Iridimi to Kounoungo and other camps. Although only one of three wells in Kounoungo is being used, it has been able to supply water to all 12,000 refugees, allowing more refugees to be moved to that camp.

Three other sites for camps have been suggested by local authorities. These are near Biltine and in the Guéréda and Iriba areas. Studies will be undertaken to determine their feasibility.

"It is not just about finding water, but also about pumping it in a sustainable way," stressed Shrestha. "When we locate a water source, we should always conduct a pumping test for 48 to 72 hours to determine the key parameters of a well that help to estimate safe yield [pumping rate] so that we don't deplete the source completely."

He cautioned that Touloum camp could face similar water shortages in the near future.

Meanwhile, a proposed site at Mader has been abandoned after geological surveys failed to find adequate quantities of water. UNHCR had originally hoped to move some 11,000 refugees to Mader from the waterless Am Nabak spontaneous site, but is now planning to expand the scope of the water search around Am Nabak.

"The possibility of finding water in Mader for 11,000 refugees is one percent," said Gabriel Salas, a UNHCR hydrogeologist based in Abéché. "At the moment, the possibilities of finding water in Am Nabak are not good but they are better than at Mader."

To boost the search for water, UNHCR last week signed an agreement with UNOSAT/UNOPS to expand the use of remote sensing technology in eastern Chad. Satellite images of selected parts in the area's north, centre and south could provide a guide to hidden sources of water in the vast desert.

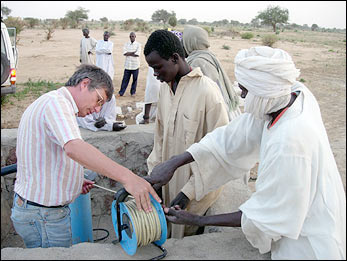

UNHCR's water expert tests the depth of the water level at a new borehole in Iridimi camp, where the water table is decreasing much faster than foreseen.

"The images and subsequent analyses will help us focus on potential areas, but equally important is the process of ground-truthing and further geotechnical investigations," said Shrestha. "We need huge teams of experts, as well as geophysical and groundwater exploration equipment to assess this huge area and verify the findings of the satellite images before we decide on where to set up new camps."

Noting that it is also a problem of capacity and logistics - "we can't mobilise resources and equipment fast enough" - he added that UNHCR is now working to identify and send more experts and geophysical exploration teams to eastern Chad.

In the meantime, the refugee agency continues to negotiate with local authorities in the search for new sites not only to replace current camps such as Iridimi but also as part of contingency planning to receive up to 100,000 new refugees in the coming months.