Congo Crisis: a 10-year-old's ordeal of flight and separation

Congo Crisis: a 10-year-old's ordeal of flight and separation

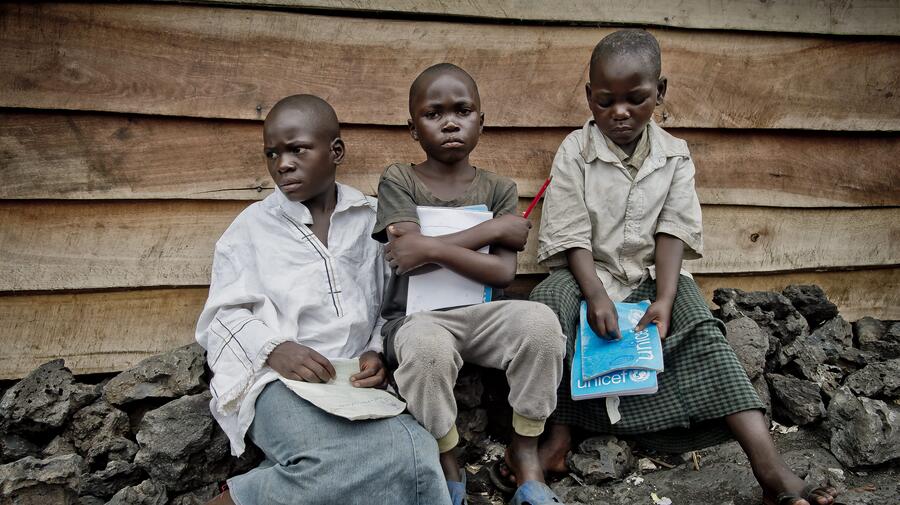

Sukuru and two of the friends he made after arriving in Mugunga III.

MUGUNGA III, Democratic Republic of the Congo, November 27 (UNHCR) - Losing a child is every parent's nightmare. The ordeal for Baseme and Eugenie was all the worse because they were separated for a few days from their 10-year-old son, Sukuru, in the middle of a combat zone, with bullets whizzing all around them and people fleeing for their lives.

That was six months ago, but over the last two weeks it must have seemed like déjà vu as fighting erupted once more in eastern Congo's North Kivu province between government forces and the rebel M23 movement. The combat forced tens of thousands of people to flee their homes, many of them seeking shelter in Mugunga III camp, where Sukuru and his family now live.

UNHCR interviewed them at the end of October before the rebel advance and capture on November 20 of the provincial capital, Goma, which led to aid agencies withdrawing non-essential staff to Rwanda and raised fears about the situation of thousands of internally displaced people in Mugunga III.

The situation remains very tense in North Kivu and neighbouring South Kivu, so a UNHCR staff member was relieved to catch up with Eugenie last weekend during the first food distribution in Mugunga III in several days. The family was doing well, despite the uncertainty, and had moved out of a communal tent and into a home built with UNHCR-funded materials. But the camp school had closed.

During the earlier meeting with Sukuru, it was difficult to imagine the despair that the bubbly boy must have suffered after losing his family during an attack on their village, located some 20 kilometres north-west of Mugunga III in North Kivu's Masisi territory.

After a relatively peaceful four years, heavy fighting had erupted in late April between government forces and the M23, which groups disgruntled army defectors. This and subsequent waves of violence and general lawlessness had by October displaced more than 220,000 people in North Kivu.

The first wave of fighting came in Masisi and forced Sukuru, his parents, three younger siblings and their neighbours to flee. "There was gunfire everywhere," the boy said in Mugunga. "We were in a panic, gunshots came from everywhere," added his 31-year-old father. Baseme said Sukuru, his oldest child, got lost in the mayhem as they fled. "When you see your neighbours lying on the ground dead, you panic," he stressed.

Children, women, the elderly and people living with disabilities are particularly vulnerable during flight and they are a big protection concern for UNHCR in volatile situations like the Congo, where displacement almost becomes a way of life. Sukuru and his parents, for example, also had to flee in 2008. Many of those on the run this past fortnight have been uprooted multiple times and they include many children separated from their families.

"I had old shoes and I could not follow," recalled Sukuru. He was terrified, but the survival instinct kicked in and he followed the flow of people fleeing the village. "I was running without seeing where I was going. I was just following the crowd. I could not stop crying because I had lost my parents."

It was an emotional time for his parents too. Once the fighting had died down, Baseme returned to the village but could find no trace of Sukuru. The boy was on the road heading towards Goma.

"On the first night, I slept under a tree by the roadside," said Sukuru, who was hungry, missing his parents and desperately lonely, despite being surrounded by hundreds of people when he reached Goma. "There were other mothers around me but they were too busy looking after their own children and belongings. They could not look after me."

His parents had already joined thousands of other newly arrived displaced civilians in Mugunga III, where they met a nurse who remembered them from 2008. She had by chance spotted Sukuru in Goma and told Baseme. "When my dad found me, I was so tired that he had to carry me on his back until we reached Mugunga camp," Sukuru recalled.

When UNHCR met Sukuru, he seemed to have moved on from the trauma of his solo trek to safety. But the fresh instability in eastern North Kivu has clouded the future and halted normal services in the camps. UNHCR and its partners are working hard to resume assistance and basic services as soon as security permits.

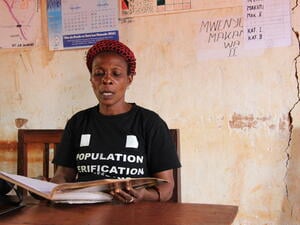

Sukuru had relished school and been positive about the future. "I want to be a good educator, a good teacher so that students understand their lessons," he had told UNHCR before heading off to school, with notebook under his arm and the volcanic hills of North Kivu as a spectacular backdrop.

But despite the latest setbacks and the trauma of life for civilians in eastern Congo, mother and son remain hopeful that he will be able to resume his education. This is also a priority for UNHCR.

The violence, meanwhile, has also prevented his father and others from seeking daily work in Goma to help make their families self-sufficient.

Concerned about the most vulnerable, like Sukuru and his relatives, and its ability to help them, UNHCR has called on all armed groups to ensure the safety of civilians. "UNHCR urges all parties to take steps to protect civilians and prevent indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks on them," Stefano Severe, UNHCR's regional representative, said last week. He also urged that the IDP camps be protected and their civilian nature respected.

By Céline Schmitt in Mugunga III, Democratic Republic of the Congo