Madagascar's Karana people still awaiting nationality

Madagascar's Karana people still awaiting nationality

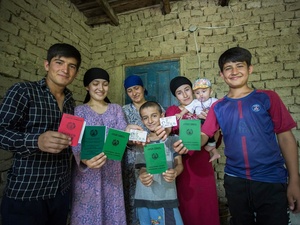

Ibrahim Ickbal is from Mahajanga, Madagascar. To date, many Karana remain unable to access any nationality.

MAHAJANGA, Madagascar – Since he was 15, Ibrahim Ickbal, a 50-year-old father of two, has worked in the same jewellery shop in the city of Mahajanga, on Madagascar’s northern coast. Although he barely earns enough to rent the two-room house he shares with his wife and children, he considers himself lucky to have a job of any kind.

Ibrahim belongs to Madagascar’s Karana community, an ethnic minority group. Although his family arrived in Madagascar from India more than a century ago, Ibrahim does not possess Malagasy nationality. Like a significant portion of the Karana in Madagascar, and like his father before him, he is stateless.

While there are no exact figures, UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, estimates that there are currently millions of people around the world who lack any nationality. The majority belong to ethnic, religious, or linguistic minorities.

When Madagascar won independence from France in 1960, most Karana were not given citizenship. Until recently, Madagascar’s nationality law only granted citizenship to children born to at least one parent with Malagasy nationality, meaning that statelessness was often passed from one generation to the next. The Karana are thought to number at least 20,000 and while some manage to run successful businesses, without access to education and formal employment, many others live in poverty.

Despite living in Madagascar for generations, stateless Karana must obtain residency permits to remain in the country legally. Recently, Ibrahim had to take out a loan from his employer in order to pay for a new biometric residence permit. “With my modest salary, it will take two years to pay back the loan,” he said. “This has been an enormous financial investment, and I still cannot vote or travel.”

Ibrahim’s new residency card describes his nationality as “undetermined”.

Olivia Rajerison, 35, knows only too well how statelessness impacts the lives of thousands of people in Madagascar. She works as a lawyer for Focus Development Association, UNHCR’s implementing partner in Madagascar, assisting stateless people to access public education and health care. In addition, were it not for a recent change of the law, Olivia’s own daughter would have been born without Malagasy nationality.

Olivia is Malagasy but she is married to a French citizen. Until earlier this year, when Madagascar amended its nationality legislation, Malagasy women married to foreign nationals could not pass on their nationality to their children. Some women got around the law by having children with their foreign partners first and marrying them later, but Olivia’s fourth child was born after her marriage. Under the previous nationality law, her daughter would not have been able to obtain Malagasy nationality and would have been considered a foreigner in the country of her birth. In cases where a father was unable to pass on his foreign nationality, children ended up stateless. Thanks to the amendment, men and women now have equal rights to pass on nationality to their children, thereby reducing their risk of statelessness.

“I feel relieved that my daughter does not have to worry about her nationality. I also feel proud that I have been able to be part of this positive change in my country through my work,” Olivia said, adding: “We still have a long way to go. There are many others who are facing great uncertainties, limitations and suffering in their lives due to lack of nationality.”

Besides the Karana, there is an unknown number of people belonging to other minority groups in Madagascar who remain stateless. In addition, the recent amendments to Malagasy nationality law still do not allow women to pass on their nationality to foreign spouses. Such a change to the law would offer a solution for people like Ibrahim whose wife is Malagasy.

In 2017, UNHCR organized consultations with the Karana community and other stateless minorities in Kenya and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, to better understand how being stateless impacts their lives. Their testimonies were then presented in a report entitled: “This is our Home” Stateless Minorities and their Search for Citizenship.

“The nationality law reform is an encouraging and important step in reducing statelessness in Madagascar,” commented Melanie Khanna, head of UNHCR’s Statelessness Section, based in Geneva. “UNHCR encourages further amendments to the nationality law to bring it in line with international standards that help to prevent and reduce statelessness.”