Not everyone flies from the cuckoo's nest

Not everyone flies from the cuckoo's nest

At the mental ward of the refugee reception centre in Debrecen, eastern Hungary, two to three refugee patients share a room and nurses are on duty around the clock.

DEBRECEN, Hungary, August 26 (UNHCR) - With their octogenarian faces and child-like excitement, a group of old refugees in a mental ward of the refugee reception centre in Debrecen, eastern Hungary, sang a sad old Bosnian sevdalinka folk song for a group of UNHCR visitors recently. Even seasoned humanitarians had to struggle with tears in this improvised mental ward, where the tides of the Balkans war stranded a group of elderly people with little hope of return.

The upper floor of the camp's clinic is reserved for those mental patients. Groups of two or three share nice sunny rooms. For lunch all patients take a little walk to the cafeteria, where they eat before the other refugees arrive. The highlight of the day is the cigarette everybody is allowed after lunch.

When visitors come, they flock around them. "Are you from the Bosnian embassy? Can we go home?" they ask in agitated tones.

The original group of 40 patients arrived in Hungary in 1992 when their mental ward in Jakes, northern Bosnia, was evacuated because of the war raging in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The accompanying medical staff admitted them to the Nagyatad reception centre and left to take care of their own families.

Over the years, some of the group were taken by their families, others died in Debrecen. Today, there are 29 of them left in the refugee camp, dreaming of the day when they can return home. "I have to go back and do the washing and ironing. There is a lot of work waiting for me," Danica says, sounding very worked up.

Maria talks of "my little baby", a child that must be an adult by now. But they all stopped counting the years a long time ago. Time is not an issue in the world these people live in.

"They are like children and we love them," says one of the caregivers in the ward. After so many years, the nurses have developed a special relationship with the group. They communicate in a ferocious mixture of Bosnian and Hungarian, but it seems to work.

For 13 years now, Hungarian authorities have been taking care of the patients, who require expensive medication and care around the clock. Every other day a psychiatrist comes to see them.

"The ward costs us 30 million forint (US$150,000) each year," says camp director Maria Terdik. "Negotiations between the Hungarian government and the Bosnian embassy have been going on for years, but we haven't found a solution yet."

The problem is quite complex. Bosnia and Herzegovina is still recovering from the destruction of war. Medical facilities are scarce, especially for mental patients. The country has no capacity to accommodate and provide care to patients within the country and is therefore extremely grateful to the government of Hungary for taking care of the group.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the mental ward in Jakes was a Yugoslav institution, meaning that patients there did not only originate from Bosnia and Herzegovina but also from other parts of the then united country. So the citizenship of some of the Debrecen patients is still unclear.

Hungary, quite understandably, would like to resolve the problem and finally repatriate the group 10 years after the end of the war - in the best interest of the patients. However, the government of Hungary made a commitment to keep them as long as no solution is found.

UNHCR followed the fate of the refugees and has been involved in the negotiations. "The people have grown very accustomed to each other. So we tried to find a solution for the group as a whole," says Lloyd Dakin, UNHCR Representative in Central Europe. "But we have to accept that such a large number of patients going to an institution would overwhelm the Bosnian mental health care system. As an alternative, we will try to identify their families and communities to see if they can go home on a case-by-case basis."

Meanwhile, the monotonous rhythm of life in the mental ward is only occasionally interrupted by visitors. Many of the patients take them aside to tell their life stories or ask for a cigarette.

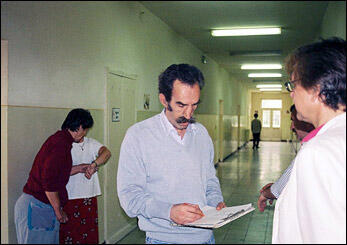

Patient Bahrija enjoys drawing visitors at Debrecen's mental ward.

Only Bahrija's aspiration is different - he wants to paint the guests. "I am an artist, may I draw you?" With a few pencil strokes he sketches the faces of the visitors on his pad. The pictures are not bad. Bahrija's remuneration is a few forints for cigarettes.

Risto has made a repatriation plan of his own. Could we please get him a passport from the Bosnian embassy? Then, he says, he would go home, get all the pension money that was not paid during the last decade, and start a new life. "I have been thinking about that for a long time. I have to go. I want to die at home," he says, "and there is not much time left."

By Melita H. Sunjic

UNHCR Budapest