Q&A: 'Including refugees in the vaccine rollout is key to ending the pandemic'

Q&A: 'Including refugees in the vaccine rollout is key to ending the pandemic'

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, is working to ensure that some 80 million forcibly displaced people in more than 100 countries are included in rollouts of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, among them 29.6 million refugees. Mike Woodman, a UNHCR senior public health officer, talked through some of the challenges with global website editor Tim Gaynor.

Whose responsibility is it to vaccinate refugees, internally displaced and stateless people?

National authorities are responsible for public health responses and COVID-19 vaccination drives. The delivery and administration of the vaccines to refugees and other people in our care will be coordinated by national health authorities. National, international organizations and civil society partners may be requested to support these efforts.

Are all governments committed to including refugees in their vaccination programmes?

UNHCR is continuously advocating at country, regional and global levels for refugees and other people we protect to be included in national strategies.

To date, out of 90 countries currently developing national COVID-19 vaccination strategies, 51 – or 57 per cent – have included refugees in their vaccination plans.

We are engaged in discussions and decision-making processes within COVAX, the global initiative to ensure rapid and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all countries.

We are working with international partners to ensure that ‘leaving no one behind’ and ‘equitable access to vaccines’ are not just phrases, but practice.

What are the risks and consequences if refugees are not included in national vaccination plans?

Using public health reasoning, it is impossible to break or sustainably slow the transmission of the virus unless a minimum of 70 per cent of the population has acquired immunity.

Ensuring that refugees are included in the vaccine rollout is key to ending the pandemic. Excluding refugees, other displaced people or non-nationals from vaccination plans carries the risk of ongoing transmission in these populations, with spillovers into the national population.

There are tangible protection risks associated with excluding refugees, ranging from consequences for their health, access to services, work, education and livelihoods, freedom of movement and freedom from discrimination.

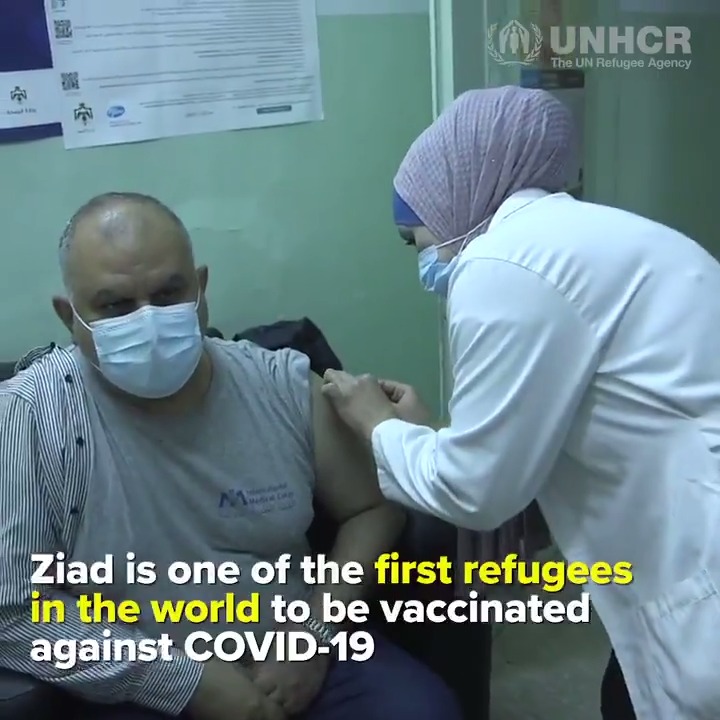

Where can we expect to see the first refugee vaccinations?

Jordan has begun vaccinating refugees. As part of the national COVID-19 vaccination plan which began this week, anyone living on Jordanian soil, including refugees and asylum seekers, is eligible to receive the vaccine free of charge.

Over the coming months, Jordan aims to vaccinate 20 per cent of its population against the virus and has currently procured three million doses of the vaccine to enable this to happen.

Since the onset of the pandemic, refugees have been included in the national response plan and have been able to access health care and medical treatment on par with Jordanian citizens.

Who will be prioritized amongst refugees?

Recognizing that vaccine availability will be limited initially, WHO’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization and COVAX stakeholders have agreed on an allocation framework to ensure that successful COVID-19 vaccines and treatments are shared equitably across all countries.

The framework advises that all countries should receive doses in proportion to their population size to immunize the highest-priority groups, such as older people, those with chronic diseases, or people who are immune-compromised. Also a top priority are healthcare workers and others with system-critical functions.

Only those refugees and other people under the care of UNHCR, who are in one of the national priority categories will receive vaccinations initially. Others may follow as rollouts are scaled up.

Is there a target time frame to vaccinate all or a majority of refugees?

It is not realistic to set time targets. The majority of countries have not yet received vaccines. But production capacities, supply and logistics bottlenecks may persist well into 2021 in many countries. The important aspect is to ensure that refugees are accessing vaccination alongside national host populations.

Eighty-six per cent of refugees live in developing countries. Some are fragile states with very limited public health systems. What particular challenges does that present in terms of delivering vaccinations?

The currently approved vaccine requires an ultra-cold continuous cold chain up to the last mile. This poses an enormous challenge for most countries hosting refugees and means a decentralized vaccination approach like those used for other vaccinations is very difficult to implement.

Most national routine immunization programmes’ infrastructure is set up to allow cold chain management to the point of vaccine administration, but the existing cold chain equipment is inadequate to handle the COVID-19 vaccine currently available. However, it is expected that more COVID-19 vaccines will be approved including those that can be managed with normal cold chain systems already in place.

UNHCR coordinates immunization activities with national immunization programmes, health authorities, health partners and UNICEF and WHO. But UNHCR does not have the technical capacity to implement vaccination activities directly. We will be working with our national partners to support the implementation of vaccination campaigns.

Among a minority of people there is some resistance to taking vaccines. How is UNHCR working to counter that?

With our health partners and the refugee communities, we are in a unique position to communicate, inform and educate about the importance of getting vaccinated and how, where and when to access the vaccines.

Getting the word out is key. To that end, the contributions of thousands of refugees worldwide who are working on the frontlines of the pandemic as doctors, nurses and public health outreach workers will be vital.