Refugee firefighters honoured for their bravery in protecting Mauritania's environment

Ahmedou Ag Albohary vividly recalls the first time he put out a bushfire at the age of 20. Armed with a tree branch, he joined a group of older men to brave the ferocious heat and beat back the flames.

“We were all together, and from that time it has been the same,” he says, his brown eyes lighting up at the memory.

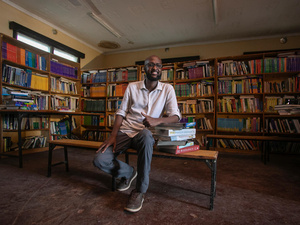

Now 57 and living as a refugee in Mauritania, Ahmedou is one of the leaders of the Mbera Fire Brigade, an all-volunteer fire brigade that has extinguished over a hundred bushfires and planted thousands of trees over the last decade. For their courage and tenacity in safeguarding lives, livelihoods and a local environment that is increasingly under threat due to climate change, the group has been named the Africa Regional Winner of the 2022 Nansen Refugee Award.

"The bushfire is a predator to us."

“We are volunteers because we have to [be],” says Ahmedou. “The bushfire is a predator to us. If we don’t go to put it out, it will burn the camps, it will burn the goats, it will burn the grass.”

Born and raised in Mali’s Timbuktu region, Ahmedou has been displaced twice by conflict – first in 1992, and again in 2012. While living in Mbera refugee camp, in south-eastern Mauritania, he grew alarmed by the number of wildfires ravaging the nearby forests and pasturelands.

Worried about the recurring devastation, in 2013 he joined dozens of fellow refugees to volunteer and help put out bushfires in the areas surrounding the camp and the town of Bassikounou in the Hodh Chargui region. Five years later, the Mbera Fire Brigade was established, with support from UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and its local partner SOS Desert.

About 90 per cent of Mauritania’s territory is desert, making it especially vulnerable to the effects of deforestation and drought. In the dry season, which runs from September through July, temperatures routinely soar above 40°c. Bushfires are more frequent during this period, and the brigade often works long shifts – sometimes 12 hours at a time, several days in a row – putting out fires.

Without proper firefighting equipment and protective clothing, the work can be dangerous. But through years of training and experience they have developed some techniques to minimize the risks.

One involves clearing large swathes of land of dry grass, to cut off the path of an approaching bushfire. Another requires more hands and coordination: when a fire is dangerously close to the camp, the entire brigade goes out, as well as many other refugees, to fetch water and pour it around the camp. When the fire reaches the damp areas, the brigade is able to put it out with branches.

“When we see a bushfire, all we have in our minds is to save and protect. We have to make sure we save the people, including those who are fighting the bushfires,” says Ahmedou. “Sometimes we are afraid, but we have courage. We make noise and we scream ‘Allahu Akbar!’ to give us the power to strike the fire.”

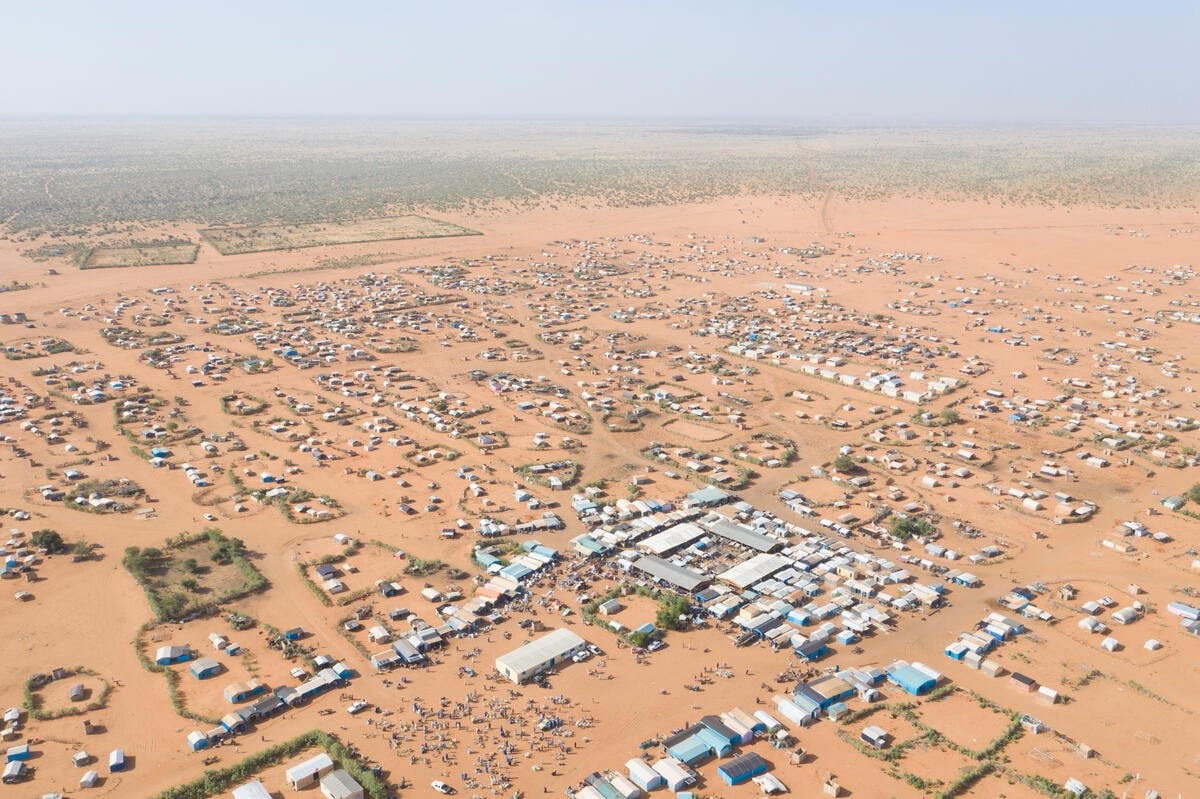

Over 80,000 Malian refugees live in and around Mbera camp, located some 60 kilometres from the border with Mali. Most of them, like their Mauritanian hosts, are pastoralists and keep large herds of livestock. As more refugees arrive from Mali with their animals every year (including 8,700 so far in 2022), the pressure on the environment is mounting.

Abou Ag Hamid, 41, is a herder from Mali who keeps nearly 50 head of cattle and sheep. He joined the brigade because he understood the need to protect the pastures that sustain his livelihood.

“Any man who sees a bushfire must go towards it and help to put it out. I used to do this back home, so it is normal. We all have animals that depend on these pastures,” he explains as he milks one of his cows.

When he is done, he walks briskly to one of the camp’s tree nurseries to water some saplings. He gets as close to the ground as he can, plucking out weeds and packing in the soil carefully around the saplings.

When they are not training or putting out fires, the volunteers spend much of their time tending to saplings and planting trees across the camp. SOS Desert supports their reforestation efforts by providing the saplings – 24,000 trees have been planted so far, with plans to plant an additional 6,000. The brigade also builds fire breaks – stretches of land cleared of dried plant debris and other vegetation that could fuel bushfires.

The brigade’s efforts to prevent and extinguish bushfires have brought the refugee and local communities together. The group now has nearly 200 active refugee members, with Mauritanians and the local authorities often joining efforts to put out bushfires, plant trees and build fire breaks.

"This spirit of volunteering is what has brought the camp together."

More voluntary groups – some led by refugees, others by members of the host community – have emerged over the years to address a range of concerns. Some are working to improve hygiene and sanitation in the camp. Others are sharing knowledge about breeding livestock, preserving pasturelands and farming techniques adapted to the increasingly dry conditions.

“This spirit of volunteering is what has brought the camp together. This is how we live. We are a people that support each other,” says Ahmedou.

Given annually, the UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award honours those who have gone to extraordinary lengths to help forcibly displaced or stateless people. It is named after the Norwegian explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen, who served as the first High Commissioner for Refugees and won the 1922 Nobel Peace Prize.

Ahmedou welcomes recognition of the fire brigade’s hard work in the name of all the volunteers in the camp, and stresses that it follows from a long tradition of learning from ancestors and caring about future generations.

“Our parents said that the one who takes care of the forest and the trees does not die in vain,” he says. “Because as long as the trees he planted exist and the forests and wildlife he protected exist, people will remember him.”