Returnees help Afghanistan's Shomali Plain to flourish again

Returnees help Afghanistan's Shomali Plain to flourish again

A UNHCR field worker discusses the projects that are helping to resurrect the village of Bagh-e-Alam on the Shomali Plain north of Kabul.

BAGH-E-ALAM, Afghanistan, July 28 (UNHCR) - The simple mud houses that returning refugees are building amid the ruins of Bagh-e-Alam testify to the extent of the devastation inflicted by war, and the current rebirth, in this area north of the capital of Afghanistan.

"You couldn't find a cat to say meow," said Attah Mir, head of the shura, the council of elders representing Bagh-e-Alam and 20 smaller surrounding villages. "The houses were burnt and all the trees had been cut down. Everything was destroyed."

But since the defeat in late 2001 of the Taliban rulers who inflicted the most damage on this area, Bagh-e-Alam has returned to life. A village, and surrounding clusters of houses, which saw the population fall from about 4,000 families to zero, is now back to some 3,300 families as the internally displaced people (IDPs) come back from other parts of Afghanistan and refugees return from Iran and Pakistan.

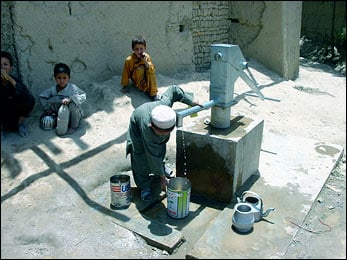

That process has been helped by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, providing material to rebuild houses and installing pumps to counter water shortages created by both drought and the deliberate destruction of the previous water system.

In the fertile Shomali Plain where Bagh-e-Alam is located - once the garden for Kabul - the UN refugee agency has helped about 14,000 families to rebuild their homes since the fall of the Taliban nearly three years ago. It has also provided more than 300 community water points.

The heavy investment by UNHCR is part of a nation-wide programme to assist the reintegration of refugees and IDPs who were driven from their homes by a quarter century of violence. More than three million Afghans have returned home in the two-and-a-half years since the programme began.

Clearly there are still obstacles to refugees returning. Security in some regions remains uncertain, drought continues to hinder the recovery of agriculture and it will take years of investment and reconstruction to reverse the devastation of decades of war. On the Shomali Plain, a frontline in the conflict between the Taliban rulers of Kabul and the Northern Alliance fighters then holding the north of the country, an estimated 50,000 homes were destroyed.

But the number of people who are returning to the area - even as de-mining continues right beside main roads - is a sign of hope.

"When we left there was war but the house was fine. It was completely destroyed when we come back from Iran," said Sheragha, who has returned with his wife and seven children to rebuild. "We took nothing with us when we left and everything was gone when we got back after eight years."

His new home, two rooms still under construction with UNHCR help, is overshadowed by the ruins of his two-storey house that had been destroyed by the Taliban. The blackened ends of timbers stick out of carefully plastered second-storey walls that speak of a more prosperous past.

Sheragha was one of those chosen for UNHCR housing assistance by the shura headed by Attah Mir. The poor farm labourer is providing shelter to his brother's widow and thinks another brother - who lost a leg to a mine before leaving for Iran - may be on his way home.

As in all the shelter programmes, UNHCR provides construction items like beams and window frames, while the recipient does most of the labour. A cash component is sometimes added to cover skilled labour, especially for beneficiaries like widows who cannot do the work.

Next to Sheragha's new home, UNHCR has assisted in the reconstruction of homes in a compound holding four families. Three came back in 2003 and the fourth arrived in 2004 after seven years of exile in Pakistan.

"We decided to come back because this is our own land and now we are feeling secure," said Bahlol Shah, who fled with his family when the village became a battleground.

As he spoke, his father was working in a nearby UNHCR cash-for-work project that has the twin benefits of repairing a karez - the ancient subterranean water distribution systems - and injecting cash into a community still struggling to re-establish itself.

At the karez, Afghan returnees were clearing a kilometre-long tunnel, descending down 65 narrow access wells as deep as 25 metres to remove both the accumulated soil from years of neglect and the deliberate destruction by the Taliban as they depopulated the area.

Despite the difficulties still facing those returning to the Shomali Plain, there seem no regrets about ending their exile. Repeatedly people say the restoration of security is enough; they know the restoration of their previous lifestyle will take years.

UNHCR has installed water pumps in Bagh-e-Alam, an essential part of the reconstruction of areas devastated by the war.

Along the main road across the plain to Kabul, Ajmal has used the training gained in a UNHCR welding programme last year to establish a small shop operating out of a battered shipping container.

Although business is slower than last year, when there was more demand for steel windows under more extensive international shelter programmes, Ajmal is happy he and his 12-member family are no longer in Karachi, the steamy Pakistani city of some 14 million people where he had found refuge.

"Many are returning. It's better if they come back to their country," said Ajmal, who received UNHCR assistance to rebuild his home in 2003. "If they come back, they will find work - things are improving, not deteriorating."