UNHCR urges states to avoid detaining asylum-seekers

UNHCR urges states to avoid detaining asylum-seekers

Many countries practise systematic detention of unauthorized arrivals - among them asylum-seekers - despite the damaging physical, psycho-social and financial impact.

GENEVA, May 11 (UNHCR) - Imagine fleeing persecution at home, surviving a difficult journey, arriving in a new country to seek asylum, only to be thrown behind bars. It sounds like a refugee's worst nightmare. Unfortunately it happens every day in many countries around the world.

While many governments are increasingly detaining asylum-seekers, there is also growing realization that this practice has a drastic human impact. On Wednesday and Thursday, officials from countries on every continent joined non-governmental organizations, human rights bodies and researchers to explore alternatives to the detention of asylum-seekers, refugees, migrants and stateless people.

The global roundtable in Geneva kicks off a series of regional discussions and was hosted by the UN refugee agency and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) with support from the NGO network, the International Detention Coalition.

"Detention is generally an extremely blunt instrument to counter irregular migration. There is no empirical evidence that the threat of being detained deters irregular migration or discourages people from seeking asylum," said Erika Feller, UNHCR's Assistant High Commissioner for Protection. "Threats to life or freedom in someone's country of origin are likely to be a greater push factor for a refugee than any disincentive created by detention policies in countries of destination."

Immigration detention - as opposed to criminal or security detention - refers to the detention of refugees, asylum-seekers, migrants and stateless people, upon entering a territory or pending their return. Typical examples include prisons or purpose-built closed reception or holding centres.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to liberty and to protection from arbitrary detention. Article 31 of the UN Refugee Convention specifies that states should not impose penalties or unnecessary restrictions on movements of refugees entering their territory without authorization.

"It is not a crime to seek asylum. Detention must therefore be a last resort, and its necessity and proportionality must be assessed on an individual basis," said Alice Edwards, a senior legal coordinator for UNHCR. "The failure of many governments to provide for or systematize alternatives to detention can put their detention policies and practices into direct conflict with international law."

In addition to the human rights and legal implications, detention also incurs health, social and financial costs. Incarceration, especially when prolonged, can cause severe psychological and physical health problems, and even lead to self-harm or suicide.

It can also make it harder for asylum-seekers who are eventually accepted to adapt to their new country, and increase resistance towards voluntary return among those who cannot stay. Some governments have been forced to pay out millions of dollars in compensation for their unlawful detention practices.

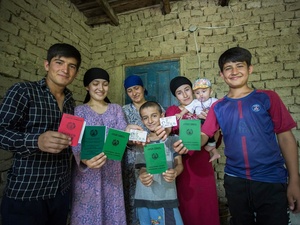

Delegates at the Geneva meeting shared global good practices on detention alternatives and practical advice on issues such as screening, assessment, community and case management, legal provision, return assistance and documentation. "The ultimate alternative is freedom - no detention in the first place, or release with no conditions," said Edwards, noting that the Philippines releases asylum-seekers from detention with no conditions and provides them with asylum-seeker certificates.

Other alternatives to detention include release on condition, such as reporting in person to renew identity documents, or reporting to the police or immigration authorities at regular intervals.

Some governments choose to release on bail. Under Canada's Toronto Bail Programme, individuals are released to a government-funded NGO that provides a full range of services, including help navigating Canada's asylum and social service systems.

Individuals are told that if they fail to appear for appointments, a country-wide arrest warrant would be issued for them. This programme has achieved considerable success, with less than 4 per cent of the individuals absconding. It also avoids the high cost of detention and saves the government approximately C$167 (US$173) in costs per person per day.

Another option involves community-based (though sometimes also government-run) supervised release or case management. Belgium, for example, runs return houses for asylum-seeker families arriving with minors as well as those families awaiting return. "Coaches" are on-site to advise and prepare families for all possible outcomes, from legal stay to return. UNHCR believes that about 30 per cent of all detainees in Belgium in 2009 were asylum-seekers. Hong Kong operates a similar programme.

"Implementing alternatives to detention can help to make migration policies function more effectively," said UNHCR's Edwards, noting that less than 10 per cent of asylum-seekers and people awaiting deportation disappear when they are released to proper supervision and facilities. "The more closely governments work with NGOs and the community on these alternatives, the more it benefits us all."

Back to Basics: The Right to Liberty and Security of Person and ‘Alternatives to Detention’ of Refugees, Asylum-Seekers, Stateless Persons and Other Migrants