Ask a Rohingya girl what she wants to be when she grows up, she might tell you she’d like to be a teacher, doctor, or even a shop owner, but for many, these are professions they may find hard to achieve. Discrimination in education for Rohingya boys and girls, particularly for professional education, has reduced the ambitions of many aspiring girls. Hence there are a limited number of role models.

Their traditional society also poses challenges with many girls and women staying at home or within their immediate circle – cooking, embroidering, and taking care of children. Outside, social expectations are strongly conservative also with a largely male-dominated public space.

In the past two years, the previously existing Rohingya refugee camp of 30,000 has enlarged into a mega-camp with over half a million refugees, and others in settlements within the district. Spaces for girls and women are a challenge. Here, as in any refugee situation, people have needs that go unmet or unnoticed – women and girls included.

This is where an innovative program set-up by UNHCR comes in. It sends trained refugee volunteers out into their own communities to identify problems and figure out ways to fix them, and it is helping to understand how refugees here can be better served by agencies with the capacity to support – like UNHCR and partners. But the volunteer program is also taking a few steps forward in the way women are involved in their communities. By including women as community outreach members, it’s challenging the perception of what women are capable of, and their role in community life.

“By reaching out to other women and girls, the women volunteers have found their own voices as they slowly gain confidence to speak for others,” says Vipawan “Winny” Pongtranggoon, a UNHCR Community Based Protection staff member. “They have earned the admiration of other women for their steadfast work on behalf of the community and by demonstrating to them what is possible for them as well.”

A great achievement in outreach efforts

As Rohingya refugees started pouring into Cox’s Bazar in 2017, challenges in assisting and protecting them emerged immediately. And because they were initially reluctant to be involved, reaching women was particularly tough.

“Meaningful participation and engagement of women is quite a challenge,” says Pongtranggoon. “Given the very conservative traditional society, if we don’t have women volunteers going out and promoting services, then it means that services we do have would not be fully beneficial, known, trusted or used.”

Under Protection Officer Carol El Sayed, the UNHCR team in Lebanon had set up a successful community-based protection model that seemed promising for Cox’s Bazar. El Sayed came to Bangladesh for a two-month emergency visit to share knowledge and expertise. When El Sayed left, Pongtranggoon took over, and completed the recruitment and training of 31 community outreach members (COMs) who would go out and unearth concerns that needed addressing both in the public realms of the camps, and the more private domains where many women were living with their unattended problems.

At first, they tread lightly. They shared important health messages about basic hygiene, chicken pox and other communicable diseases. They went around to alert people who live in crowded bamboo structures about preparing for cyclones. They reached out to those who were more isolated and potentially vulnerable: women-headed households, the elderly and disabled, unaccompanied children and others like them who were more at risk as a result of forced displacement than others.

“Before joining the COMs (program), I had never thought about helping people, helping the community,” says volunteer Ahmad Hussein, who works in Camp 13. “Now I always think about how I can help people in my community.”

Volunteers like Hussein make house calls and speak with families about their problems, providing lifesaving information and referring them to services—sometimes going with them arm in arm to get help.

“The COMs bring us closer to the refugee community and vice versa. They’re the source of information, they live in the community, they understand very well the community’s priorities, gaps in services and infrastructure,” says Pongtranggoon.

In its first year, the program grew tenfold to more than 330 community outreach volunteers. Together, their reach has been wide and meaningful. In 2018, only a year after the programme was launched, COMs conducted more than 28,000 home visits and held awareness-raising sessions on health, emergency preparedness and protection matters for nearly 435,000 people. They identified more than 25,000 refugees who needed assistance and either provided direct support or referred them to partners that could help.

For a society that has experienced discrimination in accessing education and has seen, as a result of this and other factors, limited literacy levels within the community, this kind of face-to-face oral interaction was the preferred mode of communication by refugees – and probably the only approach that could have worked so well.

“The engagement that you get from the community organizers- they’re actually a very committed team and they see themselves as having a real role in the community,” says Katie Drew, Innovation Emergency Officer. “Look what could be possible if you explore different styles of communication and really work with what you know.”

An opening for dialogue

Community outreach members went out into more and more camps in Cox’s Bazar, and sometimes encountered troubling truths. Hidden behind domicile walls were stories of abuse and neglect, trafficking and child marriage. Things that needed to be talked about: things about which people did not speak.

These refugee volunteers were aware that these issues existed. But now, they realized that what looked before like private matters were actually social problems that needed urgent responses and intervention. And they also knew they had a key role to play in providing that.

Patiently, sensitively, the COMs got to work. “When it comes to practices, traditions and norms, this is where we introduce a different approach that is more discursive and less judgmental,” says Pongtranggoon.

COMs began a campaign called “Peace in the Home,” which started with dialogue sessions where participants reflect on peace within the family, how peace is broken and what has helped them restore it. Volunteers withhold judgment and inputs, and simply facilitate as other refugees share their own experiences.

A second part of the campaign invites women, men, boys and girls to try origami, or paint and draw objects they find peaceful. As they all fold brightly colored squares of paper—a way to focus and relax over something beautiful—they begin to share. First all the things that are going wrong. And then, the things that are going right. COMs help tease out examples of home-based solutions that have worked.

“It’s not that we’re telling people what to do, it’s harnessing the good practices that people have been doing and that work for them, and they share them among themselves,” says Pongtranggoon.

Additionally, the COMs performed a play that they themselves had written with the support of a drama specialist. With themes including domestic violence and family conflicts, Pongtranggoon says some women who saw the play came forward after a performance to seek assistance. The play has already been performed and used as a medium for deeper discussions around 90 times.

More recently, they’ve added film screenings and discussions to their list of outreach activities. “For these kind of social issues we find a way that’s acceptable, digestible,” says Pongtranggoon. The visual medium of film is perfect for this community, which she has found to be highly responsive to visual media, and lacking in entertainment options.

When COMs screen “He Named me Malala,” the dialogue they facilitated afterward was rich and relevant. Refugees organically discussed the influence of family and parenting, girl education, religious practice, and how might the community improve their situation. They began talking about impediments in their own community to girls’ education and peace. Discussing the film created a safe entry point to discuss their own community.

Following an enthusiastic response from the volunteers, similar film screenings and discussions were held in 12 camps reaching more than 470 refugee viewers. A second film has been launched recently and a plan is now in place to train the COMs to run the sessions and facilitate dialogues.

Challenging what is possible

That the COMs in Cox’s Bazar belong to the Rohingya refugee community they’re serving makes them especially good at making connections and understanding issues. But it also carries with it a problem: the COMs are just as steeped in the social and cultural aspects they find others in their community contending with.

Like the women they visit, female COMs are just as likely to have a limited educational background as a result of lost or withheld opportunities. Like them, reading and writing may be skills they’ve never had the opportunity to master.

Some humanitarian programs would take the easier road of simply depending on men to go out into the community to collect, document and report on information. But for Pongtranggoon, that’s not good enough – or acceptable. She works to build capacity where there are gaps or work around them – visual medium over literacy, oral discussion on difficult topics through the medium of film.

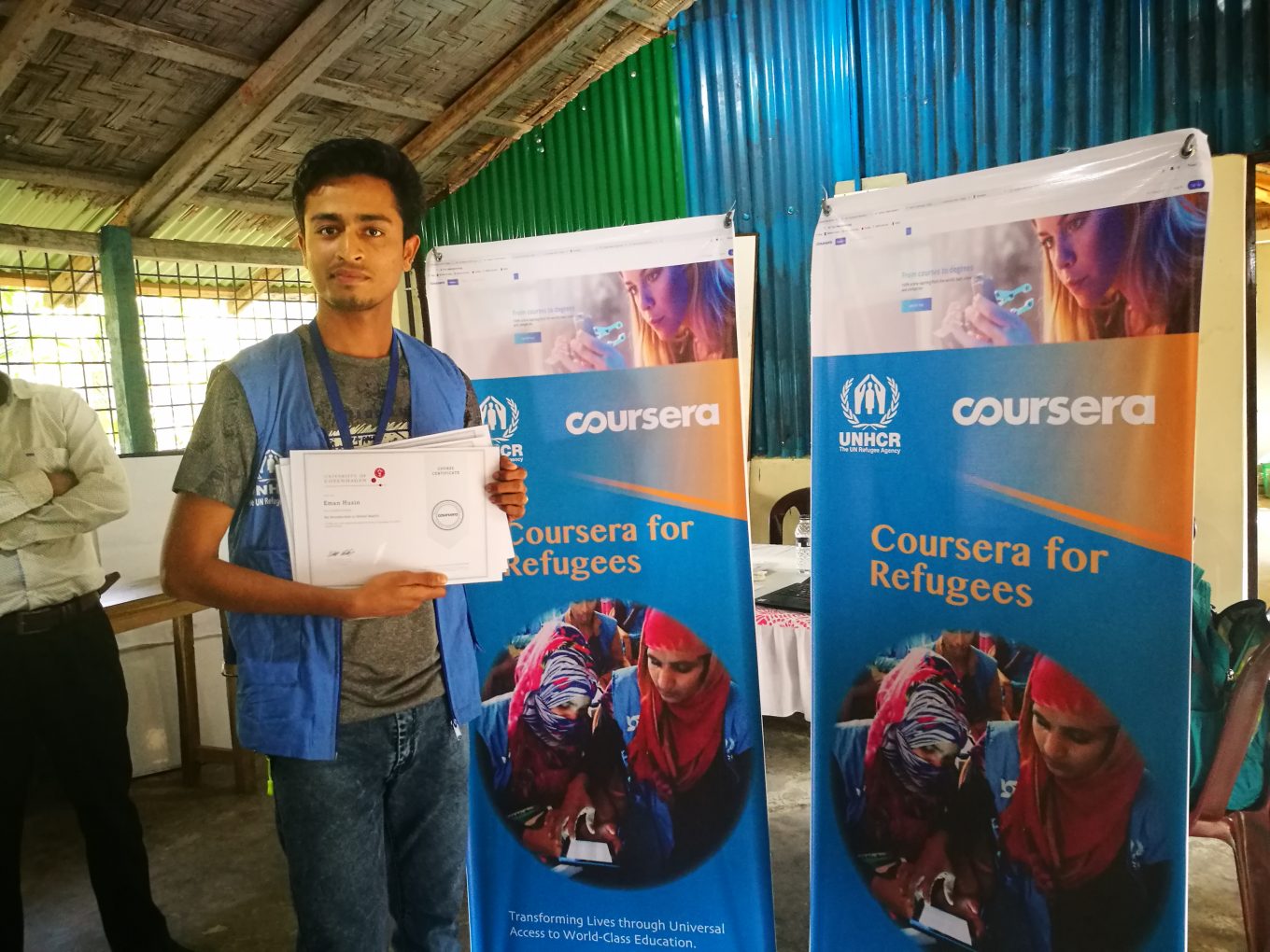

She’s made it a goal for all female COMs to learn basic reading and writing in English, while male volunteers with good language skills get access to online Coursera courses. When Pongtranggoon saw how unfamiliar- even anxious- some women were of using a tablet to record information, she refused to let the technology be a barrier to their participation, and offered women-only tablet training instead.

“They haven’t done the typical: ‘Women can’t use tech so we won’t use tech,” says Drew. “They’ve really thought about what is possible … bringing women into the conversation and mindfully thinking about ways to address that.”

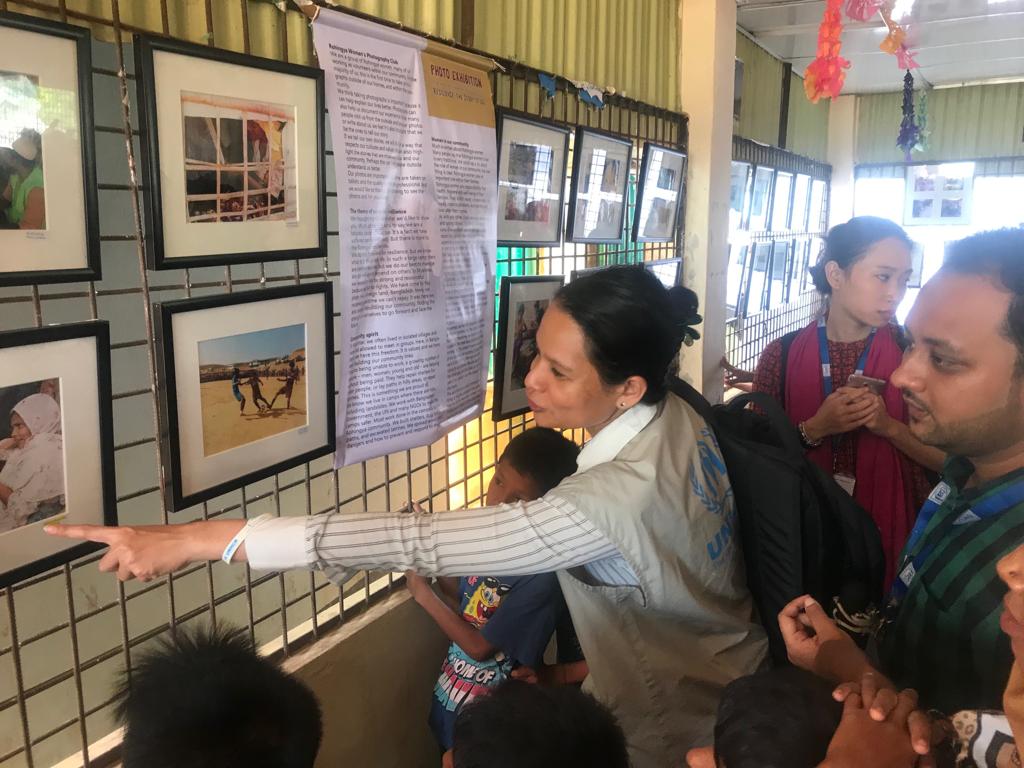

Pongtranggoon took the training even further. She showed them how to use the tablets’ camera function and brought in some like-minded colleagues to do basic photography training.

“It’s addressing a number of challenges we see from our side, and one of them is the digital divide,” says Drew. “That inclusivity piece, and bringing women into the communications ecosystem is really important so we don’t just discredit them or further marginalize them through our use of technology as a humanitarian agency.”

When the women came back from the community with their work, everyone was stunned by their natural talent behind the lens, and the intimacy of the images.

One photo was of a woman breastfeeding. One showed a woman embroidering and another a family photo of three generations. One revealed a girl child putting pasty, yellowish thanaka (a wood-based natural sunblock traditional in Myanmar) on her face and combing her hair. “We don’t see these kind of scenes,” says Pongtranggoon. “Not as outsiders.”

The initiative generated so much interest that the COMs formed a photography club to continue learning and practicing. And Pongtranggoon says their images continue to reveal hidden Rohingya culture while bolstering the COMs’ own sense of confidence.

“Photography is an empowering experience for refugee women and girls because usually they are photographed and we write about them…for reports or publications,” she says. “But refugees being able to represent their own community and show to others how they see things from their own perspective… For me it’s another step forward for women.”

The photography club members got the opportunity to display their first set of seventy photos to the public during a photo exhibition on World Refugee Day this June, attended by the U.S. Ambassador to Bangladesh who personally commended the women involved.

Committing acts of bravery

The COMs program in Cox’s Bazar works because of the trust it has built within the community. The COMs, with access to information and communication with UNHCR, have in-depth and accurate knowledge on issues they’re raising awareness about, like the importance of registration, or the MoU UNHCR and UNDP signed last year with Myanmar that had raised questions in the community around repatriation.

The COMs program is also a success because of the level of trust and cohesion volunteers have with each other. “It’s a collegial – even a familial atmosphere amongst the COMs, our partners and UNHCR,” says Pongtranggoon. Along with field support that includes plenty of feedback and encouragement, the COMs are also in touch with a WhatsApp group and have direct access to one another and UNHCR and partner staff for support. And they know that the agencies are taking their safety seriously. That’s important, because there are voices that are negative or potentially threatening.

Some traditional proponents of male-only roles have been suspicious of the presence of women in spaces where they were historically excluded.

Pongtranggoon and her team continues to recruit women despite the constraints. Men and women COMs work in pairs, something she knows is revolutionary here. “Women and men don’t often work shoulder to shoulder, doing the same job and getting the same return,” she says.

Women who stand up in front of community and religious leaders to facilitate dialogue sessions are committing almost unthinkable acts of bravery. “In the presence of men women don’t usually talk, that’s not their traditional place,” says Pongtranggoon. But in the role of volunteer, they are able to take up a space, and be heard. They have support from the authorities here, and it is recognized that many Rohingya men have also recognized the value of their contribution.

It’s changing the way these female volunteers see themselves too. “Being a COM now, I am well known and well accepted by the community,” says volunteer Koshmeda, who works in Camp 13. “Before joining the COM program, I couldn’t communicate with people and felt shy. But now I can confidently communicate with people and I am able to provide them information.”

Koshmeda used to stay inside all the time, and says she had no awareness of issues beyond her door. Not anymore.

For Pongtranggoon, empowering Rohingya women to change the way society sees them—just a little at a time—is a victory. But changing the way they view themselves is probably more meaningful.

“Slowly, slowly, I started to see them emerging, and becoming more confident in themselves,” she says. “For me that is something I feel very moved by. The aim is not any kind of social revolution, but simply, there’s a need for women to better understand their entitlements and independently access information, services, assistance and support for themselves, their families, and for the community as a whole, both here and in Myanmar. It’s a credit to the women and their community to see this through – you feel that they see value in it and believe also it will benefit everyone.”