CHAPTER 2:

Moving up

Christine Night, 16, South Sudanese refugee, dreams of becoming a pilot after completing her studies. ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane

For millions of refugee children, finishing primary school means reaching the end of their educational road.

Of the 4 million refugees who were not in school last year, more than half were missing out on secondary education. Less than one in four young refugees go to secondary school.

The impact of the war in Syria shows how conflict and displacement can spell the end of a child’s education. In 2009, before the fighting erupted, 94 per cent of Syrian children attended primary and lower-secondary education. At the end of 2017, enrolment in formal primary and secondary education in the five biggest host countries – Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt – stood at 56 per cent. This is a ten per cent increase compared to the end of 2015, when 46 per cent were enrolled across these five host countries. Nevertheless, this still leaves some 700,000 Syrian school-age refugee children out of accredited education.

©UNHCR/Kıvanç Ayhan

“When I could not speak Turkish, life was really tough.”

Mohammed, 24, and his sister Enas, 23, Syrian refugees, both learned Turkish through a language support programme that facilitates access to higher education. UNHCR cooperates with the Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities to offer an intensive, advanced Turkish language programme for refugees. Mohammed is now a student in the Arabic-Turkish translation and interpretation department at Yıldırım Beyazıt University in Ankara. Enas will start university in Turkey in September. She and her brother hope to set up a private translation company in the future.

Making the leap

Secondary education requires subject specialist teachers and more sophisticated learning materials, as well as science laboratories, well stocked libraries and access to the internet.

As refugee children grow older, they are often expected to take on a greater proportion of family responsibilities or to go to work, often in the shadow economy or in overtly illegal activities. This can make the opportunity costs of continued education – on top of uniforms, exercise books and textbooks, transport and possible school fees – too great for refugee families to bear.

Photo ©UNHCR/Anthony Karumba

Mercy Akuot, 24, South Sudanese refugee, fled home as a teenager after her parents forced her to marry a much older man. She escaped first to Uganda, and then to Kakuma refugee camp in northern Kenya, where she now supervises a women and girls’ empowerment project, working with families to teach them the importance of educating girls and ending harmful cultural practices.

But the lure of teenage labour can be countered by community outreach programmes that promote the long-term benefits of education as well as financial help for families with school-age children to offset the potential loss of income.

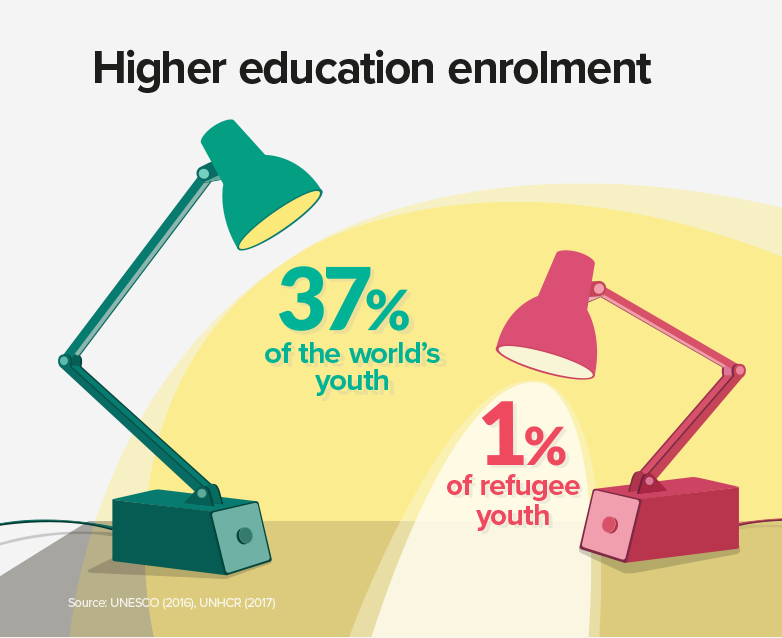

An obvious result of lack of access to secondary education is that refugee enrolment in higher education is devastatingly low. Globally, only one per cent of refugees are able to gain access to higher education.

Finding solutions to shortfalls in educational access requires sustainable, long-term investment and planning. But there are other obstacles that could and should be overcome more readily. The most significant barrier to higher education is cost.

Schools and universities often insist on certificates proving that examinations have been passed or courses completed, documents that refugees often leave behind in the sudden dash for safety. Even when these documents are readily available, qualifications may not be recognized in the new country or may not be regarded as equivalent to the local system. Yet not recognizing refugees’ unique situations and barring them from the next level of their education because of bureaucracy is callous and counterproductive.

Similarly, although refugees frequently arrive in countries where they do not speak the language, to view this as a reason why they should be barred from the classroom is to overlook children’s innate language-learning ability. Several countries – from Rwanda to refugee-hosting countries in Europe, including Turkey – have demonstrated how prejudicial this assumption really is, with refugee children learning the language of their hosts in a matter of months when they are given the opportunity. This helps refugee children integrate and make friends and also supports them in accessing and succeeding in education.

©UNHCR/Gabo Morales

“I didn’t only find peace in Brazil, I found a future.”

Salim Alnazer, 32, Syrian refugee, works as a pharmacist at JadLog, a transportation and logistics company in São Paulo, Brazil. His pharmacy degree from a Jordanian university was validated in Brazil with the help of Compassiva, a Brazilian NGO that helps steer refugees through the complex process of certifying their professional qualifications.

Showing the way

The true power of education is perhaps best expressed by those who have defied the odds and made it all the way through higher education. Refugees not only bring skills and talent to their countries of exile, they also possess tremendous potential that education can unlock.

Twenty-six years ago, UNHCR and the Government of Germany set up the Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative, best known by its acronym DAFI, to provide higher education scholarships to refugees. Among them is Hawo Jehow Siyad, who was a six-year-old Somali girl when she arrived in Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya, in 2000. Hawo not only managed to complete her primary and secondary education in Dadaab; in 2012 she was the top student in Garissa County, where Dadaab is located.

©UNHCR/Caroline Opile

“We’re getting the opportunity to give back to society.”

Hawo Jehow Siya fled Somalia and arrived in Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya, when she was six years old. After graduating from the University of Nairobi with a DAFI scholarship, she returned to Somalia where she now works as a database officer.

A DAFI scholarship sent Hawo to the University of Nairobi to study economics and statistics. After graduating she returned voluntarily to her native Somalia in the hope that she could serve her war-torn country. After a spell at the Ministry of Transport and Aviation, she moved on to a job at a World Bank-funded project, where she now works as a database officer. In Hawo’s words, DAFI scholarships have transformed her life and the lives of numerous other refugees, giving them “the opportunity to give back to society.”

In the quarter century of its existence, DAFI has enabled more than 14,000 refugee students to study at universities and colleges. This programme expanded significantly in 2017, with more than 6,700 refugees enrolled in 720 universities and colleges in 50 countries around the world. UNHCR’s ambition is to continue this positive trend and see this number rising exponentially in the coming years, by bringing on more partners and diversifying opportunities, including through connected learning, a blend of digital and in-person study that can be done without physical access to a university. Addressing barriers to entry such as poverty, lack of certification and language acquisition will be key to achieving this aim.

Hawo’s achievements show that when refugees can access quality education and complete their studies, they can stand on their own feet, give back to the countries that sheltered them and, one day, help their home communities to rebuild and to flourish.

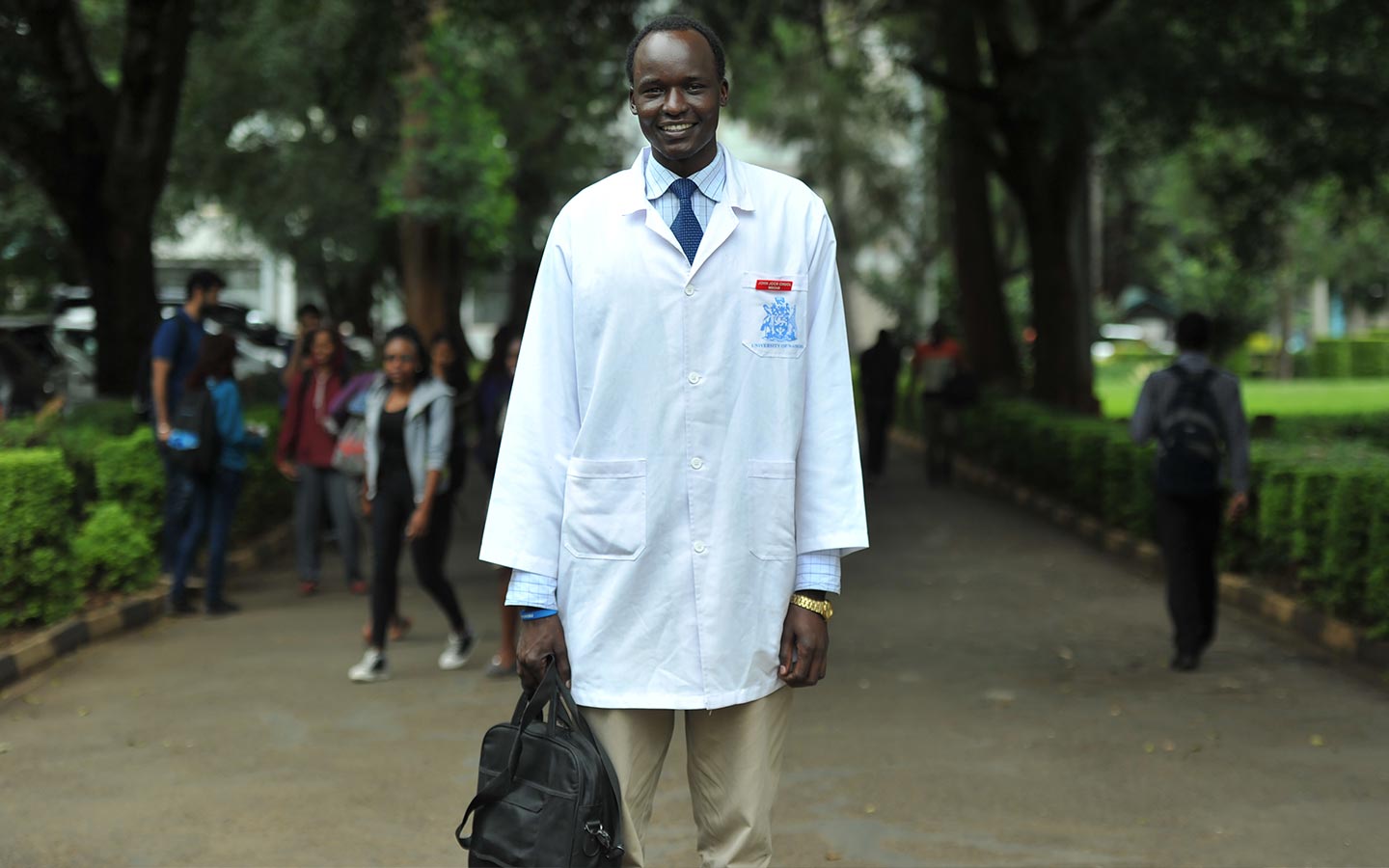

©UNHCR/Anthony Karumba

“Since I was in primary school, I knew I wanted to be a doctor.”

John Jok Chuol, 24, fled South Sudan’s conflict when he was eight years old, finding safety in Kenya’s Dadaab refugee camp. He is now pursuing his dream, studying for a Bachelor of Science degree in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Nairobi on a DAFI scholarship.

Reason for hope

UNHCR is committed to turning the tide to enable refugees to get the education they deserve. In 2016, the 193 UN Member States committed to better support refugees and the communities hosting them. Primary among these commitments is their determination to provide inclusive quality education in safe learning environments for all refugee children. Education is also central to the global compact on refugees, which has been developed with Member States as part of a two-year process.

A promising example of progress can be seen in the countries neighbouring Syria, where intensive efforts to improve refugee education are beginning to reap rewards. Recognizing that many Syrian refugees had completed their secondary education before fleeing the country, host governments, donors, academic institutions and education actors have intensified their support for higher education. As a result, enrolment of Syrian refugees in universities across four of the largest host countries – Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq – reached 5 per cent in 2017[6], an improvement on the global average of one per cent, but nevertheless still a huge gap compared to global access to higher education, which is 37 per cent.

Afghan refugees at school in Belgrade, Serbia. A Farsi interpreter is helping them get up to speed in their new classroom. ©UNHCR/Imre Szabó

“I would like to go home one day when the war is over… In the meantime, I will study to become a doctor and learn how to help people back home.”

– Zaman, 13, Afghan refugee

CASE STUDY

Childhood regained

How a teenage mother found her way back to the classroom

Regina Juwan, 16, South Sudanese refugee, had to quit her studies when she became pregnant at the age of 14. She is now back in school at Kiryandongo refugee settlement in Uganda thanks to an Accelerated Education Programme. ©UNHCR/Yonna Tukundane

When Regina Juwan found out she was pregnant at the age of 14, it looked like her childhood was over. Not only would she now have a baby to look after, but it seemed her education was finished – her school asked her to stay away until after she had given birth.

But then Regina’s childhood had already been brutally cut short. She was 11 when civil war erupted once again in her native South Sudan. Both her parents were killed in front of her. She remained beside their bodies for an entire day until her aunt found her and the two of them fled to Uganda. It took them a long and exhausting month to reach safety. “We hid in the bush, we got hardly any sleep and ate very little – and sometime nothing for days,” says Regina.

Once in Kiryandongo refugee settlement, in the country’s midwestern region, the government allocated a plot of land to Regina, her aunt and other family members who joined them. After a while Regina even started going to school – until 2016, that is, when she was forced to abandon her studies to give birth.

“I loved being in school, being with my friends, playing netball and studying,” says Regina. “I was so angry when my teacher said I should drop out because I was pregnant.” But unfortunately that is standard practice, as schools do not want to be held responsible for supporting students like Regina when they are expecting.

Two years after giving birth, to a daughter she named Blessing, Regina was able to return to Victoria Primary School. But she had fallen well behind. Therefore, she was enrolled in an Accelerated Education Programme – a flexible programme for overage out-of-school children and youth which provides learners with equivalent, certified competencies for basic education and allows them to transition back into the formal system. In Uganda, the programme compresses seven years of formal primary education into three years; once Regina has completed the second level (grade five), she will resume her formal studies next year in grade six.

Bringing up a baby has meant big changes for Regina – as well as an extra mouth to feed. But when she is in school she is able to recapture some of her own childhood in the company of her classmates. “We study together, we play, we chat – and we completely forget about [everything else].”

Inspired by the care and compassion of the nurse who delivered her baby, Regina has decided to become a nurse herself. But Oryema John, the head teacher at Victoria Primary and supervisor of the accelerated education programme, is worried for her and others like her. “Many children [in Kiryandongo] are still out of school,” he says, “and those who complete their primary schooling have little chance to enrol in secondary classes because of poverty and a lack of decent learning spaces, school supplies and qualified teachers.”

In Uganda, 63 per cent of the roughly 355,900 primary-level children are enrolled in school, but that falls to only one in 10 of the 141,900 secondary-age children and youth – and only one-third of those students are female. UNHCR, in its role as chair of the Accelerated Education Working Group, has been working with the Government of Uganda and other partners to recognize accelerated education as an important strategy for out-of-school children and youth like Regina.

For years, the Ugandan government has worked to meet educational demand for refugees and their peers from local communities in the face of funding shortages. But the education ministry, together with UNHCR and other partners, intends to launch an education response plan in September 2018 – a strategy incorporating accelerated education so that girls like Regina can resume their rightful place in the classroom.

CASE STUDY

Machine learning

Robot-mad brothers pursue love of science in new school

Kevin, 11, and his brother Jason, 14, Guatemalan refugees, fled to Mexico to escape violence. In their new school in Saltillo, they are able to pursue their passion of robotics and science. ©UNHCR/Encarni Pindado

Jason and Kevin González* are robot crazy. At school in Guatemala, the brothers signed up for robotics workshops and were encouraged to take part in science competitions.

The two of them even managed to win first prize in their category in a national robotics contest. For the science-mad duo, life seemed great. “We had everything a kid could want,” says Jason, 14.

“And all of the sudden, we had to leave behind the life we knew.”

Like thousands of refugees from the North of Central America region, Jason, his 11-year-old sibling and their father fled the gang-related violence in Guatemala and headed north for Mexico.

According to UNHCR’s Global Trends report, by the end of 2017 the number of asylum-seekers and refugees from the region had reached more than 294,000 – up by 58 per cent from the year before and 16 times more people than at the end of 2011.

Once over the border to Tapachula, in southern Mexico’s Chiapas state, the Gonzalez’s applied for refugee status and the boys set about trying to restart their education.

But that was not as easy as abc. “The first school we tried did not accept my kids,” says Andres, the boys’ father. “They said they had no spaces, but we felt it had more to do with us being foreigners, Central Americans.”

Eventually, with the support of UNHCR partner RET International, a humanitarian organization focused on education, the children were enrolled in a public boarding school, where they stayed during the week and went back to their father for the weekends. For children so recently uprooted from their homes, it was not ideal, but at the time it was the only option to continue their studies.

Seven months later, all three were granted refugee status and enlisted in a UNHCR programme through which recognized refugees are relocated to “integration spaces” in northern and central Mexico.

The González family joined almost 400 refugees who have started new lives in Saltillo, Coahuila state, where the heads of families can work legally and where there children can enrol in school.

At their new school, the González brothers quickly excelled. Jason only had his primary school diploma from Guatemala, but he was able to take a standardized knowledge test so that he could start the third year of junior high school in August 2018. “This way, I’ll finish junior high within a year and catch up the time I lost when I was forced to leave Guatemala,” he says.

Although Jason was new, his teachers and classmates recognized his talent and made him team captain in a local science contest, “Knowledge Jeopardy”. They won first prize.

Even during the summer break, Jason and Kevin are not wasting time. With help from their dad, they are building a robot that looks like WALL-E, the character from the Disney/Pixar movie.

So where will this robotics obsession take them? The brothers say they want to work together – and are dreaming big. “I want to be the boss of my own company, where we will produce electronic devices and high-tech robots,” says Jason. “I want to be a scientist like Albert Einstein, or Nikola Tesla. I want to do so many things, I can hardly wait.”

* Names have been changed for protection reasons.

[6] UNHCR and American University of Beirut, Issam Fares Institute (2018)