Conditions in Western Saharan refugee camps worsen as exile lengthens, food aid wanes

Conditions in Western Saharan refugee camps worsen as exile lengthens, food aid wanes

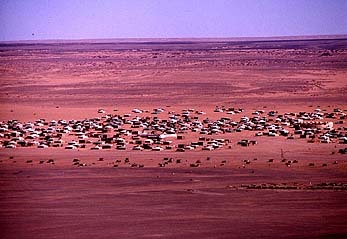

The desolate Dakhla Camp for Saharawi refugees in Algeria.

TINDOUF, Algeria, March 28 (UNHCR) - Relief workers assisting refugees from Western Sahara living in four camps in an isolated corner of Algeria report deteriorating health and nutritional conditions, particularly among women and children.

U.N. refugee agency staff who recently visited the desert camps found that the refugees are suffering from a lack of funding and irregular food aid deliveries due to lapses in donor contributions to one of the international community's oldest and most intractable refugee problems.

The needs of the Western Sahara refugees were brought before the U.N. Security Council by High Commissioner Ruud Lubbers, who briefed the world body on February 7 about pressing refugee issues around the world.

"Western Sahara is an example of a protracted refugee situation where there are few immediate prospects for durable solutions and where programmes to assist and protect the refugees remain severely under-funded," Lubbers told the Security Council. "This is unacceptable."

A joint U.N. inter-agency mission that visited the refugees in February came back with a grim assessment.

"The Saharan refugees are really surviving on a hand-to-mouth basis," said UNHCR senior food aid coordinator Laura Lo Castro, who visited the camps together with officials from the World Food Programme. "Their basic food aid needs over 2001 were met only irregularly due to frequent breaks in the food pipeline."

Supplying the Sahrawis with assistance in their remote desert refuge has always been a challenge. The World Food Programme provides basic items - including flour, lentils, vegetable oil and sugar - when they are available, an increasingly rare occurrence. Supplies of meat, vegetables and fruit are not part of the U.N.'s standard assistance package. The vital items must be purchased by those refugees who have the financial means in a region with virtually no income-generating activity.

"Food aid arrives every month, but not the right quantities, and it's always the same, year after year," said Lo Castro.

World Food Programme officials concur, saying they have been trying to work with donors to ensure a stable supply of food aid to the remote camps. "The WFP operation for the Western Sahara's refugees has been one of the worst funded, with alarming ups and downs in contribution levels," Werner Schleiffer, who heads the food agency's Geneva office, said in a statement last year.

Dakhla Camp in Algeria.

The plight of the Saharan refugees dates back to 1975, when Spain gave up its mineral-rich North African colony.

The nomadic residents of the vast desert area became victims of a territorial dispute involving both Morocco and advocates for an independent Western Sahara. At the time, the nomads had no idea their exile in the remote Algerian camps would stretch well beyond a quarter century.

The U.N. negotiated a cease-fire in 1991 between the Polisario Front and the forces of neighbouring Morocco, but a proposed referendum to decide whether Western Sahara would become independent or part of Morocco became bogged down in disputes over who is eligible to vote.

The Algerian government estimates that 165,000 Sahrawi refugees live in four camps along the country's border with the Western Sahara. Three of the sprawling sites are located near Tindouf, while a fourth camp is more remote, some 180 kilometres distant.

Sahrawi refugees lead the barest of existences and are afflicted with a variety of nutritional and vitamin deficiencies, according to aid workers. Thirty-five percent of the children suffer from chronic malnutrition and another ten percent from acute malnutrition, which may explain evidence of stunted growth among the exiles, local NGO workers say. The children also have a low level of iron in their blood.

Refugee women are also similarly malnourished. Forty-five percent suffer from iron deficiencies, which aid workers say might be caused by their unvarying diet and because the vitamin pills so popular in developed countries are shunned in the Sahrawi culture.

Lo Castro says that at least some of the Sahrawis' nutritional problems are due to their relatively settled lives in the remote camps. Historically surviving on camel meat and milk, the Sahrawis now largely rely upon what they receive from the U.N.

"Part of the problem is their consumption patterns and food habits," Lo Castro said, noting that many of the Sahrawis rely too much on starchy foods, as well as sugar, butter and other disparate items that arrive in the camps from a few small donors. The lack of potable drinking water in the desert camps also contributes to some of the refugees' health problems.

Adequate supplies of drinkable water are difficult to find and expensive to maintain in the parched desert region, and many of the Sahrawis have long relied on substandard water sources that barely meet the U.N.'s standards. UNHCR is spending $700,000 this year to upgrade water supplies and sanitation facilities to the some 70,000 refugees living in El Aiun and Awserd camps, up from the $180,000 the agency spent for water and sanitation on all four camps last year.

But no amount of funding and food aid will resolve the plight of the Sahrawis. Says the U.N.'s Lo Castro: "If a political solution is not found, what is going to be the destiny of these refugees?"