Stepping into the world's worst humanitarian crisis

Stepping into the world's worst humanitarian crisis

UNHCR and OCHA staff interviewing internally displaced women in the South Darfur town of Yara.

Editor's note: Parts of this story were amended after publication to address sensitivities raised by some of our readers.

EL GENEINA, Sudan, August 3 (UNHCR) - As the UN refugee agency's top man in Nigeria, Eusebe Hounsokou is accustomed to conferring with presidents and prime ministers. But at the moment, he's instructing a Sudanese boy on how to transfer water from leather saddlebags to a storage tank in the new UNHCR compound in West Darfur without spilling half of it.

"Here I have to do everything - even running after donkey water. It's all part of the job," Hounsokou says with a trademark laugh.

For all the members of UNHCR's advance team in Darfur - the world's worst humanitarian crisis - setting up shop in this remote, isolated area has been an exercise in flexibility. Led by Hounsokou (UNHCR's representative in Nigeria), the team had to start from scratch to open offices and a house for the staff in El Geneina, capital of West Darfur, and Nyala, capital of South Darfur. An office is also planned for El Fasher, capital of North Darfur. UNHCR's team in Darfur is planned to rise to 30 staff.

In Darfur, a region the size of France, where some one million people have been displaced by 17 months of fighting, water is a scarce commodity. Like the local townspeople, aid workers have to buy it from young boys who collect it at the town well and transport it on donkey back - donkey water, as it's called.

With an influx of relief agencies quickly pushing up prices, houses were available for rent in these small dusty towns that pass for capital cities, but they generally lacked any amenities international staff would expect - like windows, roofs, toilets, electricity or water. And don't even mention furniture.

That's why Roland-François Weil, UNHCR's first protection officer in Nyala, found himself spending hours in the local market negotiating for beds, mattresses, chair, drinking glasses and knives. More sophisticated equipment, like generators, a refrigerator and office furniture, had to be flown in from Khartoum. Even drinking water had to be flown to El Geneina from the Sudanese capital.

"It's important for the staff, when they first arrive, to feel they have a base somewhere," Weil explains. "They have to feel comfortable, to know they have a bed to sleep in and someone to cook food for them, so they don't have to go to the local restaurants where the hygiene is questionable. This is the basic we have to have to be able to do our jobs effectively."

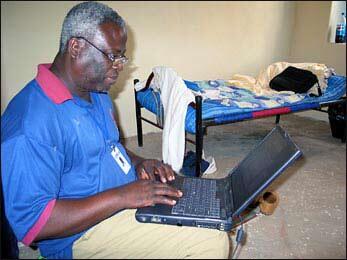

UNHCR's Eusebe Hounsokou in his bedroom that doubles as an office in El Geneina, West Darfur.

Like all aid workers in Darfur, UNHCR staff are aware that even at its most basic, their living conditions are many steps above those of the people they are here to serve.

"It's the old question - who protects the protectors?" says Hounsokou. "We have to be in good shape ourselves to serve refugees," or, in the case of Darfur, internally displaced people.

For the UNHCR staff who arrived in late June, though, literally without a mattress to sleep on, it's been easy to identify with the problems the displaced people face.

Because UNHCR's new house-cum-office in El Geneina had no latrine or toilet, Hounsokou found himself in the absurd position of travelling around town with toilet paper stuffed in the pockets of all his trousers and in his computer bag.

"I was terribly rude," he recalls with a laugh. "I'd be visiting someone, but I'd be thinking: When is this person going to finish talking so I can use his toilet?" (Some international agencies had been operating in Darfur for a year or so, and had better facilities.)

Food, too, cannot be taken for granted. Upon moving into UNHCR's office-home, Weil was thrilled to have a gas ring to cook on. "Some nights we have eggs, sardines, rice and peas, but sometimes we have peas, eggs, rice and sardines," he says with a wry smile.

UNHCR staff are accustomed to operating under difficult conditions. It's not the first hardship posting for Hounsokou, who has worked in Somalia, Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic in his 15 years with UNHCR. And he supervised building of the Kakuma refugee camp in north-western Kenya from scratch in 1992.

"This situation in Darfur is better than in Kakuma. In Kakuma we had just the land, we had to build everything. Here we are starting from zero, but in Kakuma we were starting from zero, zero, zero. Some zeros are more zero than others," he adds with another laugh. (Keeping a sense of humour saves one's sanity in situations like this, he adds.)

UNHCR's mission in Darfur is to make sure the Sudanese government lives up to the commitments it has made to the international community, and to ensure that displaced people are not sent back to their burned-out villages against their will. Trying to protect displaced women against rape in their makeshift camps is another priority.

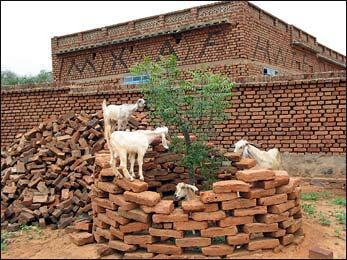

Under construction - UNHCR's office in El Geneina.

Now that the staff have beds to sleep on, a steady water supply, and nutritious food hygienically prepared, they can focus on protecting the desperate displaced Darfurians.

"It's a good feeling to see how our operation has grown," Hounsokou says. "Now our staff can do their jobs and you can see the impact we are making."

By Kitty McKinsey in Nyala and El Geneina, Sudan