Dream home comes closer for Serbian family years after fleeing Croatia

Dream home comes closer for Serbian family years after fleeing Croatia

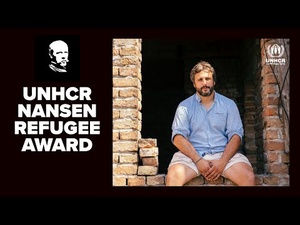

Ranko Rajković outside the barn where he currently lives. He wants to knock it down and have a more solid and comfortable house built on the adjacent land under a regional programme.

OBRENOVAC, Serbia, February 26 (UNHCR) - On a recent cold and misty morning, Ranko Rajković shows visitors around the converted barn where he lives in central Serbia and tells them that he just wants to tear it down and build a decent home with a separate bedroom for him and his wife.

"My [wife] Željka has been dreaming about a decent, solid house for the last 15 years," the 54-year-old, with tears welling in his eyes, tells UNHCR in the home he and his wife share with their student son. That dream could soon come true under a regional housing scheme in which UNHCR is a stakeholder.

Ranko bought the tumbledown barn in 2002, seven years after fleeing from Sisak in neighbouring Croatia. He, Željka and son Saša, now aged 21, were among a quarter of a million ethnic Serbs who escaped to Serbia at the end of the 1991-1995 war in Croatia.

The family had moved in 1997 to Obrenovac, and have lived there ever since. Ranko soon found a steady job with a local bakery while Željka resumed her teaching career and now runs classes for primary school children. They soon decided to make their future in Serbia and applied for citizenship in 2002. "We were aware we would not return to Croatia, as we had no property to go back to," Ranko explained.

Instead, they decided to invest in the land in Obrenovac, rather than spend money on rent. The barn was never meant to be more than a stop-gap measure for the couple, whose son studies law at Belgrade University, some 30 kilometres away, during the day.

But they never had enough money to buy or rent somewhere better and as the years passed, Željka's dream never seemed to get any closer. Then Ranko heard about a major project aimed at ending the lingering problem of displacement in the region.

The Regional Housing Programme was launched by Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia in 2012 to provide durable housing solutions and sustainable livelihoods for some 74,000 people, including 45,000 in Serbia. Donors have to date pledged some 260 million euros of the estimated 600-million-euro cost, with the bulk pledged by the European Union (230 million euros).

"When I heard about the Regional Housing Programme on TV and talked to local staff of the Serbian Commissioner for Refugees, I had no doubts as to what I would do," said Ranko, who has applied for one of an initial 70 kit houses to be built in Serbia. Apartment blocks are also being constructed or renovated under the five-year scheme, with the support of UNHCR.

Here is a bungalow that has already been constructed in the Serbia town of Pozega. If his application is successful, Ranko and his family will move into something similar.

Ranko is one of 80 applicants for the sturdy, well-built bungalows and if his bid is successful, he will need to apply for a location and building permit. He wants to tear down the barn and build on an adjacent site. He already has connections in place for the utilities, which will save expense on installation. UNHCR will hire local contractors to build the homes after a competitive bidding process.

Having a new house will help make the sacrifices of the past seem worthwhile as well as ensuring comfort and security as Ranko and Željka grow older. One of the reasons they could not build anything better in Obrenovac was because they were investing much of their savings in Saša's future.

"We saved every penny we earned to put our son through school and to be able to find a permanent housing solution other than renting accommodation," Ranko recalled. In central Croatia's Banija region, where he grew up, Ranko was an administrator and accountant for a local school, where Željka taught. They lived in an apartment owned by the school.

On arrival in Serbia, still strong and energetic, Ranko found a job as a handyman for a bakery. With Željka's earnings as a teacher, they were living off a monthly income of 200 euros at a time when the economy was deteriorating. They did not even have enough money to install plumbing inside the barn and had to use a tap outside to get water. In the winter, Ranko wrapped cloth around the pipe to prevent it from bursting.

They hoped that when Saša left secondary school he would learn a trade such as becoming a plumber, so that he could join the labour market as quickly as possible and help with expenses. "However, his mind was set on law and we had to give in. He commutes for nearly three hours to and from Belgrade every day in order not to miss lectures and comes home in the evening," Ranko said.

But now they see some light at the end of the tunnel. Saša's studying could benefit them all when he starts working, and they might soon have a new improved home. As for Croatia, it is a foreign country for the Rajkovic family - like the past.

By Mirjana Ivanović Milenkovski and Neven Crvenković in Obrenovac, Serbia

For more, please go to http://www.regionalhousingprogramme.org/22/about-international-stakeholders.html