Legal Catch-22 leaves newborn child with citizenship "unknown"

Legal Catch-22 leaves newborn child with citizenship "unknown"

The right to nationality is an internationally accepted fundamental human right - yet Glody's status remains unclear.

BUDAPEST, Hungary, December 29 (UNHCR) - "Mother and father Congolese, the citizenship of the child unknown," reads the entry for nationality on the birth certificate of Glody. The three-month-old boy is one of those children born to refugee parents in Hungary and so is registered with unknown citizenship.

"I feel at a loss… no one can tell me what it means, but a word like 'unknown' never means good," said Glody's father, 37-year-old Leon Mukaba, as his youngest son slept peacefully in his lap.

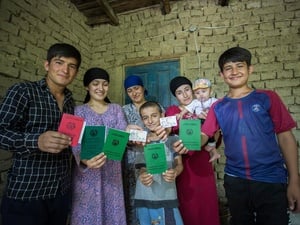

Mukaba fled his home in the Democratic Republic of the Congo about four years ago after falling afoul of the authorities due to his political views. Two years later, after he was granted refugee status in Hungary, his wife, Céline, and their three children were able to join him through the family reunification programme.

Today the family of six is building a new life in the capital, Budapest. Together they wrestle with Hungarian, said to be one of the most difficult languages to learn. Mukaba works shifts in a warehouse, while Céline cares for the baby, picks up the older children at public school and manages the paperwork required to get medical care, receive a family allowance, and pay the rent and utilities in their new home.

One of those documents is the birth certificate for Glody. While acknowledging that he was born in Hungary in September 2011, it leaves him a citizen of no country - a boy too young to crawl or speak caught in an undeserved Catch-22.

Under the current policy, a child born to foreigners on Hungarian soil is generally not entitled to Hungarian citizenship. Instead, the parents are expected to furnish proof of the child's foreign citizenship - in the form of a certificate issued by the home country -so that it can be recorded on the birth certificate. Otherwise, the citizenship must be registered as "unknown".

Yet parents who have been forced to flee their homeland may not be able to obtain such documentation easily. Contacting the authorities in their home country might put their lives in danger or jeopardize their refugee status, as cooperation from these officials might imply that they no longer need protection.

Without such written proof, these newborn children are caught in a legal limbo.

"The well-being of children without citizenship is seriously at risk," said Ágnes Ambrus, UNHCR's protection officer in Hungary. "Without a legal bond with the state, they could be denied basic rights and services - including access to education and health care."

Glody caught one break when he was two months old. To help maintain family unity, he was granted refugee status, which ensures him the same rights Hungarian children have, with a few exceptions.

But while refugee status may seem to be the solution, it is not a lasting one.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child both state that everyone has the right to a nationality. In many cases, as with Congolese law, children automatically acquire the citizenship of their parents. But the situation of refugee children is particularly tricky because they are outside their home countries and cannot contact their authorities for proof of this legal bond. While many refugee families are never able to return home, some families still hope to do so one day.

Fortunately, Glody's refugee status provides him protection. For other refugees who are stateless, however, it is important that host countries grant citizenship to stateless children born on their territory.

Meanwhile, Mukaba is studying hard for the Hungarian citizenship exam. The test includes written and oral questions - all in Hungarian - about the country's politics, history and literature. Recognized refugees are eligible to apply for citizenship in Hungary after staying at least three years. If Mukaba passes the exam, his wife and children can be naturalized through him.

Determined and optimistic, he attends an exam preparation class every Thursday evening. "My favourite topic is the one on popular vote because I think that is important for a country," he said while reviewing some of the course material.

Then he pulled a Hungarian dictionary from a pile of books on his table to quickly look up the pronunciation of the word "hope".

"We are waiting now and we hope, the only thing we can do," he concluded.

By Eva Hegedus in Budapest, Hungary