Chapter 2:

Investing in inclusion

Mahmoud, 9, Syrian refugee in Sweden (left) was resettled from Egypt after a traumatic attempt to reach Europe by boat. © UNHCR/Johan Bävman

Under one roof

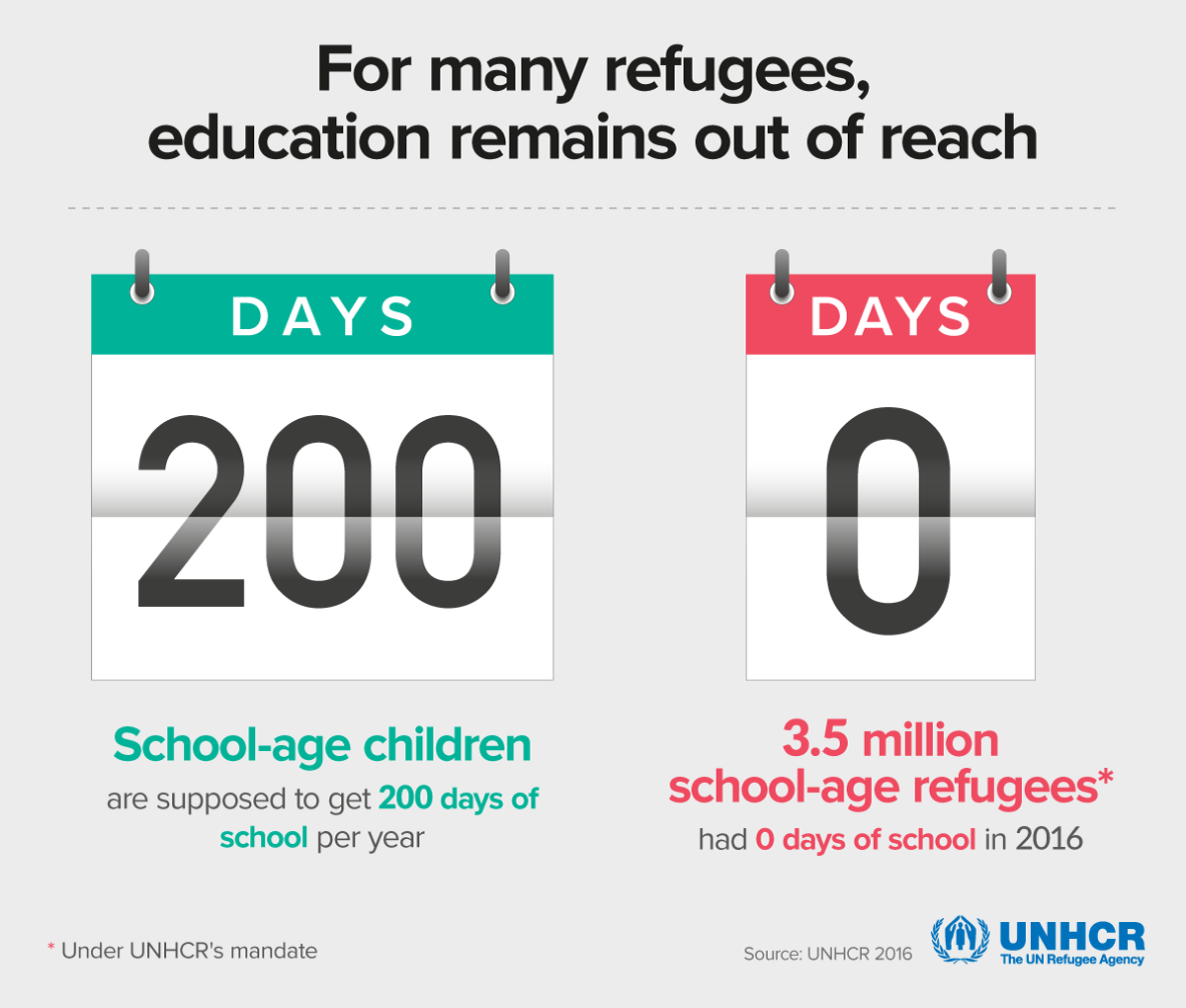

The day a refugee child starts school in their host country marks a turning point – a move away from the chaos of fleeing home and towards the normality of life as they used to know it. Yet the reality for too many refugees is exclusion from the sanctuary and opportunities that school affords. In 2016, there were 6.4 million school-aged refugee children under UNHCR’s mandate, all of whom required approximately 200 days a year of school. Some 3.5 million didn’t get a single day.

There is no short-term fix for the education of refugees. For millions, exile has lasted decades. In 2016, only 552,200 refugees returned to their countries of origin, and only 189,300 were resettled. Education for refugees condemned to years of forced displacement is arguably the best means available to change the fortunes of the people of these conflict-stricken countries. Experience has shown that the most sustainable path to this end is to ensure that refugees are systematically included in national development planning, as well as education sector plans, budgets and monitoring systems.

Ensuring inclusive education for refugees is already a clear responsibility for UN member states under international treaties – commitments that were renewed under Sustainable Development Goal 4 and its promise to “ensure inclusive, equitable quality education for all”, as well as in the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. But governments and the international community must also grasp another crucial point. Humanitarian organizations have to prioritize new emergencies as they arise; education for refugees, on the other hand, is a social service that requires long-term planning, technical support and funding.

Developing countries need global support

Developing countries bear the brunt of the global refugee crisis: more than 84 per cent of the world’s refugees are hosted in developing regions, and 28 per cent are in the least developed countries – that is 4.9 million people. As a result, refugees often find themselves in places where resources are already stretched. Even where the national policy is to include refugees in education systems, funding and support from the international community is falling short.

© UNHCR/Gordon Welters

“They want to know about us and we want to know about them. There’s so much to tell and explain. Sometimes I translate for the others into Arabic or German.”

Kamala, 10, Syrian refugee in Golzow, Germany.

When refugees and the children of the host community learn side by side, investment in a shared system will create long-lasting improvements for the community and ease tensions over the extra strain on local resources. Building new schools and training more teachers improves the quality of a country’s education system for future generations – be they refugees or citizens of the host country. By contrast, admissions policies that discriminate against refugees – either because of their refugee status, or because of their gender, or because of disability – are unacceptable, not to mention counter-productive. Neither should it be forgotten that education is a lifelong endeavour. Ensuring that adults have access to education of all levels is another way of enhancing their independence, self-sufficiency and dignity.

Knowing the road ahead

A recognized exam certificate can make the difference between access to further education or seeing the door closed. Extra efforts need to be made, therefore, to overcome the challenges refugees face to stay in school – challenges that are particularly acute as refugees reach adolescence and face pressures to start working, get married and devote themselves to domestic duties. Enrolment levels for refugees drop starkly as they transition from primary to secondary education, often because secondary schools simply do not exist, are too costly or are too difficult or dangerous to reach. It is unsurprising, therefore, that a mere one per cent of refugee youths make it to tertiary education.

An effective response to the challenges of educating refugees cannot be based on unpredictable annual funding and short-term planning. Funding needs to be substantial and long-term to enable governments around the world to build more schools and train more teachers, thus making a lasting contribution to the development of the host country. Such ambitions entail responsibilities and costs, and the international community must share them. But if we do treat education for refugees as an investment in sustainable development, it will mean everyone can win.

Case study

Mutual understanding

Lydiella Hakizimana, 13, Burundian refugee attending class at Mahama refugee camp, Rwanda. © UNHCR/Anthony Karumba

Two years ago, Lydiella Hakizimana knew no more than a few words of English. Now it is her favourite subject. As the bell rings out to herald the start of the day at Paysannat L School, just outside Mahama refugee camp, she is at her desk, ready to begin.

In 2015, as civil unrest in Burundi arose over disputed elections, Lydiella, her mother and her three sisters joined the stream of refugees into neighbouring Rwanda. Today there are more than 50,000 refugees in Mahama, a camp close to the Burundian border.

Keen to regain some semblance of stability in her life, Lydiella, aged 13, looked forward to resuming her education. But there was a problem: in Rwanda classes are taught in English, not French as in Burundi.

UNHCR and the Rwandan government devised a solution. Together, they set up a system that enables refugee children to plug into Rwanda’s national curriculum: a comprehensive, six-month bridging course, locally known as the orientation project, that includes English lessons. It is one of many such initiatives UNHCR supports around the world to boost refugees’ education and help them move into a formal learning environment.

Refugees who largely missed out on an education at home go through the entire course. Others are enrolled in state schools at a suitable level as soon as they are ready. At the 2016 UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants, Rwanda pledged to help include Burundian refugees in the national education system. It is striving to live up to that promise.

New horizons, and new friends

The bridging course introduced Lydiella to more than another language. It educates students in other subjects, too. “We realized we needed to integrate refugee students into the national system as they faced serious barriers to coping and adapting,” says Charles Munyaneza, UNHCR’s associate education officer based in Kigali.

The bridging project started at Mahama with 2,500 students in June 2015. Since then, more than 19,000 children have passed through it. “It is a really crucial step towards including refugees in the national education system,” says Munyaneza.

Paysannat L is one of several schools in the area with the Paysannat name – with a total student population of almost 20,000 – but it is the only one where refugees and local students learn side by side. Jean-Claude Muhyemama, the deputy head, says that having a common language has played a big role in integrating the two communities and fostering good relations. “This project has really helped the Burundian students get to the same level as Rwandan students,” he says.

Jean Harindwa, Lydiella’s English teacher, has been working at the school since it opened its doors in 2015. Himself a Burundian, he says teaching English has helped him with his own mastery of the language.

“Most of these students fled their country and they didn’t think they would ever learn again,”

On the ground:

New horizons

Hani al-Moliya, 19, Syrian refugee, pictured outside his shelter in the Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

I miss myself, my friends, times of reading novels or writing poems, birds and tea in the morning.

My room, my books, myself, and everything that was making me smile.

Oh, oh, I had so many dreams that were about to be realized…

This short poem was sent to me a couple of years ago by a remarkable young man named Hani al-Moliya. We first met when he was still a teenager living in a Syrian refugee settlement in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley. At the time, I asked him what he had taken with him when he fled his home.

Hani looked up at me, smiled and said: ”I took my high school diploma. I took it because my life depends on it. Without education, I am nothing.”

Hani had already proved his determination to get an education. To get to school in Homs, his home city in Syria, he had to dodge soldiers and snipers. Sometimes his classroom would reverberate to the sound of bombs and shells landing. Such a desire to keep going to school terrified his mother, who implored him every day to give it a miss. He kept going, saying that his determination to finish school outweighed his fear.

In the end, however, the family had to flee. Hani’s aunt, uncle and cousin were murdered in their homes for refusing to leave their house. Their throats had been slit.

In Lebanon, Hani and his family found respite from the war, but they also found gruelling hardship and monotony – no jobs, no education, and dwindling hope. Not that you would ever describe Hani as someone lacking in hope, given the maturity and self-assurance he radiates. Despite an incurable eye condition that means he is legally blind, he has never given up. His response to this affliction was to take photographs, and lots of them; in Lebanon, he would record daily life among his fellow refugees incessantly. The camera lens became his eyes – it is how he sees the world. More than that, though, he turned out to have a real talent for photography.

Before too long, fortune smiled upon the family and they were granted asylum in Regina, Canada, where they have now settled down. Hani is now majoring in computer engineering at Ryerson University in Toronto. He says it was hard getting back to his studies after a break of four years, but he has thrived on being back in a “school community” and making new friends. And he is still writing poetry.

When people ask why the world’s refugee problem is our collective problem, I often think of Hani – a boy so determined to learn that he risked his life to go to school, who reached for his high-school diploma when he had to leave almost all his other possessions in Homs. As he said in the poem, with his books, his friends and his home life, Hani had so many dreams. To realize those dreams, he doesn’t want charity and handouts – just the chance to live a normal life and to have the educational opportunities that will let him stand on his own two feet.

This is why we need for more universities to offer scholarships to refugees, to help counter the terrible statistic that says only one refugee in 100 has access to a place in tertiary education. This way, we invest in young people as brave, resourceful and determined as Hani al-Moliya. This way, we invest both in the richness of our own societies and in the future prosperity of the countries they once called home.

Melissa Fleming is the Chief Spokesperson at UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency.