Chapter 3:

Champion teachers

Mohammed, Somali refugee living in Melkadida camp, Ethiopia, teaches refugee women how to read and write Somali and English. © UNHCR/Diana Diaz

Children all over the world need great teachers, but refugees need them all the more – academic tutors but also mentors, motivators, protectors and champions. Without their dedication and perseverance, there would be no schools to go to. Investment in a teacher of refugees is therefore an investment in the futures of hundreds, if not thousands, of children.

Teachers must be properly supported and motivated.

Teachers involved in the education of refugees need adequate and regular pay. But other measures to help them feel like respected professionals – participation in decision making, improvements in working conditions and support for substantial professional development and certification – also contribute to the motivation, quality and attitude of teachers with some of the world’s most challenging jobs. Without this, the chronic teacher shortages that hamper the education of refugees and their host communities will persist.

In the world’s toughest classrooms, the teachers must be qualified

Like all other children, refugees deserve qualified teachers who are knowledgeable in how they teach and what they teach. These teachers, if they are to develop and progress in their profession, require access to continual training opportunities to help them develop, add new skills and find solutions to problems they encounter in the classroom.

Digital innovation can enhance classroom learning but cannot replace it

UNHCR strives to offer refugees connected learning programmes with accredited courses through partnerships with academic institutions, using a mix of onsite and online interactions with instructors, tutors and their peers. Connected learning has been particularly successful in remotes places where resources are low, and is invaluable where it is hard for refugees to physically attend university.

Yet teachers remain central to the success of such programmes. Massive open online courses are sometimes perceived as an acceptable substitute for refugees, yet they have extremely high dropout rates. Learners find the material short on relevance or are put off by the impersonal nature of sitting in front of a computer and watching a video lecture. Only 1 per cent of refugee youth are in tertiary education; this statistic will not be improved by asking refugees to learn exclusively online.

Teachers and students need access to quality materials

Children learn best with a variety of tools and experiences which are appropriate to their age and are culturally, linguistically and socially relevant. However, all too often, refugee teachers and the children in their classrooms do not have access to adequate materials. To get some idea of the scale of the problem, in Ethiopia, 15 refugee learners have to share the same book.

“If you teach the mother, she will teach her daughter how not to suffer how she has suffered.”

© UNHCR/ANTHony KARUMBA

“Our students are more determined to succeed because they can see that their teachers are so motivated to support them achieve their goals.”

Yel Luka, South Sudanese refugee teacher, Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya.

What do teachers say?

Unsurprisingly, the response of teachers depends on the circumstances they face and the level of support they receive. Some speak of being “overwhelmed”; others say students can spot teachers who are supported and motivated, and that makes them “more determined to succeed”. In Yemen, where children and adolescents from both refugee and host communities are going to school in the middle of a war, teachers speak of having to counsel children who have witnessed appalling violence and who may have lost close relatives, including one or both parents. Yet they keep turning up to work despite the omnipresent danger, delayed or unpaid salaries and the bomb-damaged classrooms.

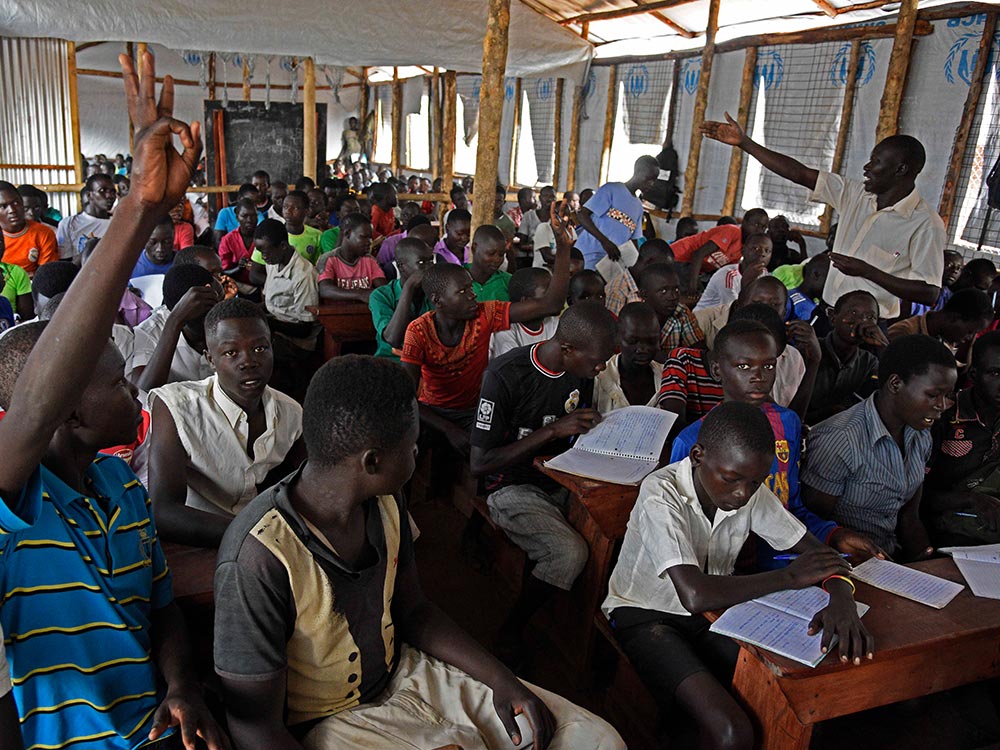

© UNHCR/Isaac Kasamani

“Things are really tough here because there just isn’t enough space for all the students.”

Ugandan deputy principal, Patrick Abale, teaches a class at Yangani Progressive Primary School in Yumbe District, northern Uganda.

Teachers with access to the experience and advice of their colleagues around the world, both online and face-to-face, are getting the professional support they need to succeed in their extremely challenging working environments. This approach should be the default. Leaving teachers without support networks and opportunities to develop would be unthinkable in any well-developed educational system; there is no justification to do so with those entrusted with the futures of refugee children.

Case study

Medical miracle

Mojtaba Tavakoli, 22, former Afghan refugee, at the Medical University of Vienna where he is embarking on his PhD. © UNHCR/Gordon Welters

Ten years ago, Mojtaba Tavakoli was a 13-year-old Afghan refugee who had barely survived the journey overland to Turkey and then across the sea. Eventually he wound up in Austria, alone, penniless and frightened. His brother had not survived the voyage.

This year, Mojtaba graduated from the Medical University of Vienna with a BSc in molecular biology and he is about to embark on a PhD in neurodegenerative disorders. “We must dream big,” he told his fellow Afghan students at a graduation ceremony in Vienna – and Mojtaba has certainly lived up to his own maxim.

Tragedy strikes on the journey to a new life

As a boy, he spent much of time time helping his parents on their farm in rural Ghazni province, in eastern Afghanistan. Mojtaba received a basic education but, as he puts it, “there was no science in my childhood.”

The farm was surrounded by members of the Taliban, and Mojtaba’s family faced heightened risks as they came from the persecuted Hazara ethnic minority. “Sooner or later, we were going to be attacked. Europe was our only hope of safety.”

The family sent him and his brother Morteza, 18, ahead to see if they could find a base to establish new lives in Europe. On the sea crossing between Turkey and Greece, Morteza drowned. Mojtaba was left to continue the journey alone.

After making it to Austria, he was taken in and in effect adopted by an Austrian couple. Marion Weigl, a health-care specialist, and Bernhard Wimmer, an environmental scientist, welcomed the Afghan teenager into their home and, once he had a place in school, introduced him to the wonders of science.

The extended family unites

After being granted asylum in Austria, Mojtaba was able to bring his Afghan family to join him. At the prize-giving ceremony, Mojtaba had both his Afghan and Austrian parents looking on. His father, Joma Ali, was swollen with pride. “This is a good evening,” he said.

The rest of his family was there, too – three sisters and one brother. The youngest ones are still in school but the oldest girl, Sohela, 21, was present to receive a school prize before she heads to university to study physics.

A slight, bespectacled figure, Mojtaba pulled no punches in his speech when it came to the difficulties for refugees trying to integrate themselves into Austrian society. He called on fellow Afghans to take an interest in politics and get involved in shaping the future of their new homeland. Not content with the remarkable transformation of his own fortunes, he helped to found the Association of Afghan Pupils and Students in Austria, whose members he exhorted to press on with their achievements.

“I have a dream,” he told them, speaking in fluent German, “that one day an Austrian government minister will have Afghan roots, and that someone from our community will win a Nobel prize.”