Creating art in arid no man's land

Creating art in arid no man's land

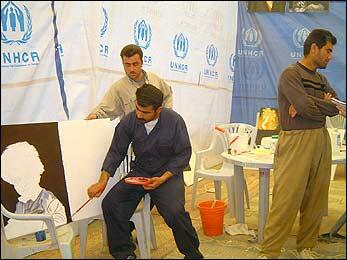

The painting workshop in Al Karama makeshift camp on the border of Iraq and Jordan.

AL KARAMA, Jordan (UNHCR) - The victim's naked reddish body lies on a black background. His face is contorted with pain and disbelief while a black crow standing on his forehead watches two hawk-headed men stick their cutting claws into their prey's flesh, one plunging his head to devour the victim's heart, the other opening his hooked beak ready to bite greedily at the man's amputated arm.

"It is an expression of very hard feelings," says the artist, Azad, an Iranian Kurd who has spent 24 of his 29 years in refugee camps. "It is my own view of the times we are living in. Times when Man does to his brother things wild animals do not do to each other. According to the law of the jungle, animals do not eat the flesh of their same species. But in our world, the so-called humans unscrupulously devour their brothers."

Like the bulk of the 1,150 refugees living on this one-kilometre stretch of arid ground in the no man's land separating Jordan from war-torn Iraq, Azad is an Iranian Kurd who fled Iran with his family in 1979 when they were accused of helping the opposition and their communities were attacked.

Seeking safety, they ended up in Al Tash refugee camp in Iraq, where they remained cloistered till the American-led coalition troops entered Iraq in March 2003. Fighting and instability forced them into a new exodus to the gates of Jordan's borders, where they were denied entry.

The makeshift border camp at Al Karama is home to a diverse group of Iranian, Iraqi, Palestinian, Somali and Sudanese exiles. They fled the risky situation in Iraq to seek safety in the camps installed by UNHCR after Amman agreed to provide temporary protection, initially for three months, for all Iraqis fleeing the fighting and instability. Iranians previously living in Iraq's Al Tash refugee camp were refused entry to Jordan, others were stopped for security or other reasons. A year later, they are still stranded in the desert.

"Muzzled for all our life, we express our grief, fear of an uncertain future and despair of a bleak present through our paintings and drawings," says Azad.

His Palestinian counterpart, Bassem, explains, "Three months after arriving here, we asked CARE [UNHCR's implementing partner] for colours, crayons and paper and we started this vocational training project."

Al Karama's artists conduct twice-weekly painting classes with materials from CARE.

The material was provided and an off-white hangar-shaped tent serves as the workshop. Along with five other refugees, Azad and Bassem give painting lessons twice a week: "One for the many children of the camp and the second for older refugees willing to learn."

Hanging on the tent's material, the paintings form an alignment of stories of broken lives, shattered dreams and unbearable fear.

On a hospital metal bed, tears flooding from the eyes of a terrified child's greyish face are a poignant reminder that children are the most fragile victims of conflicts.

Human bones scattered on arid red sand, a skinny naked child burying his face into the dust in a desperate search for food, tell all about the famines that devastated the Horn of Africa in the past years. "It is the work of an African refugee. I am sure he saw many children die of hunger before his eyes, maybe even his own," says Bassem.

Other images include a shaggy-haired woman in her sleeping dress running in the dark carrying a baby, and a screaming mouth emerging from a thick wall symbolising political oppression.

Bassem portrays famous personalities like German musician Ludwig Von Beethoven and Lebanese immigrant poet Gibran Khalil Gibran. In a sad laugh, he denies having a taste for Beethoven's melodies. "I am a refugee living in a tent in the middle of nowhere, where only strong winds whistle in my ears. How would I have the means to listen to classical music?"

In contrast to the strong colours used in most of the paintings, a pale gouache drawing stands out like a ray of hope in the middle of this gallery of disarray.

A smiling little girl with a round face and wide green eyes waters a flower growing in front of her tent. "This is my daughter Najar," says Azad proudly. "I hope that her future will be happier than her present. That one day she will be free, live in a home, go to school and grow a garden to make up for the desert she was born in."

By Lamia Radi

UNHCR Egypt