Released from captivity

Released from captivity

"Many times I tried hiding my daughter under my coat so they wouldn't take her," 35-year-old Sherine tells me through her tears. "They would come in randomly and take young girls. My daughter was nine years old. Eventually they found her. She is now with them."

I'm sitting on a mattress in the big hall outside Lalish Temple in the Shekhan district in northern Iraq, where Sherine, a Yazidi woman released in January 2015, is recounting her five horrific months in captivity. "Some girls were throwing themselves off the mountain to avoid being taken and raped," she murmurs. "Many girls just killed themselves. I tried to kill myself a few times too."

Her lips tremble when she thinks of what her own children have experienced. "My 18-year-old daughter was taken one week after we were imprisoned in Mosul. I just can't think about what she must be going through. I can't think of what they must be doing to her."

Sherine is one of the many Yazidis in Iraq who have been captured by insurgents over the past year. They are persecuted, tortured and even killed for their religious beliefs.

Murad, a man in his sixties, knows the horror well. "They kept us is a hall with almost 3,000 people," he tells me. "It was so difficult to breathe. It was suffocating."

I try to picture what it must have been like. Thousands, crammed into a hall, with little or no food. Not allowed to leave, shower or even speak. The thought sends shivers through me.

"We were all loaded onto buses," Murad continues. "People were crying, we were saying goodbye to each other. We really expected that we were headed to our deaths. We were separated into elderly, young men, young women and disabled people. Mothers were hugging their daughters, saying goodbye as they were pulled apart. Some people were fainting, they were so terrified."

Murad arrived the day before, on a convoy of 11 buses. Covered in dust, they carried some 200 people who had been dropped near Kirkuk, in northern Iraq, after being held captive for over five months. Many of the survivors developed serious skin infections. Some of them, frail and gaunt, can no longer stand up straight.

Among the passengers was a 15-year-old girl with disabilities. "She could not have been in a worse condition," the priest tells me later. "She was bruised all over. They had tortured her; her back was covered in wounds. She also told us that they tried to rape her several times."

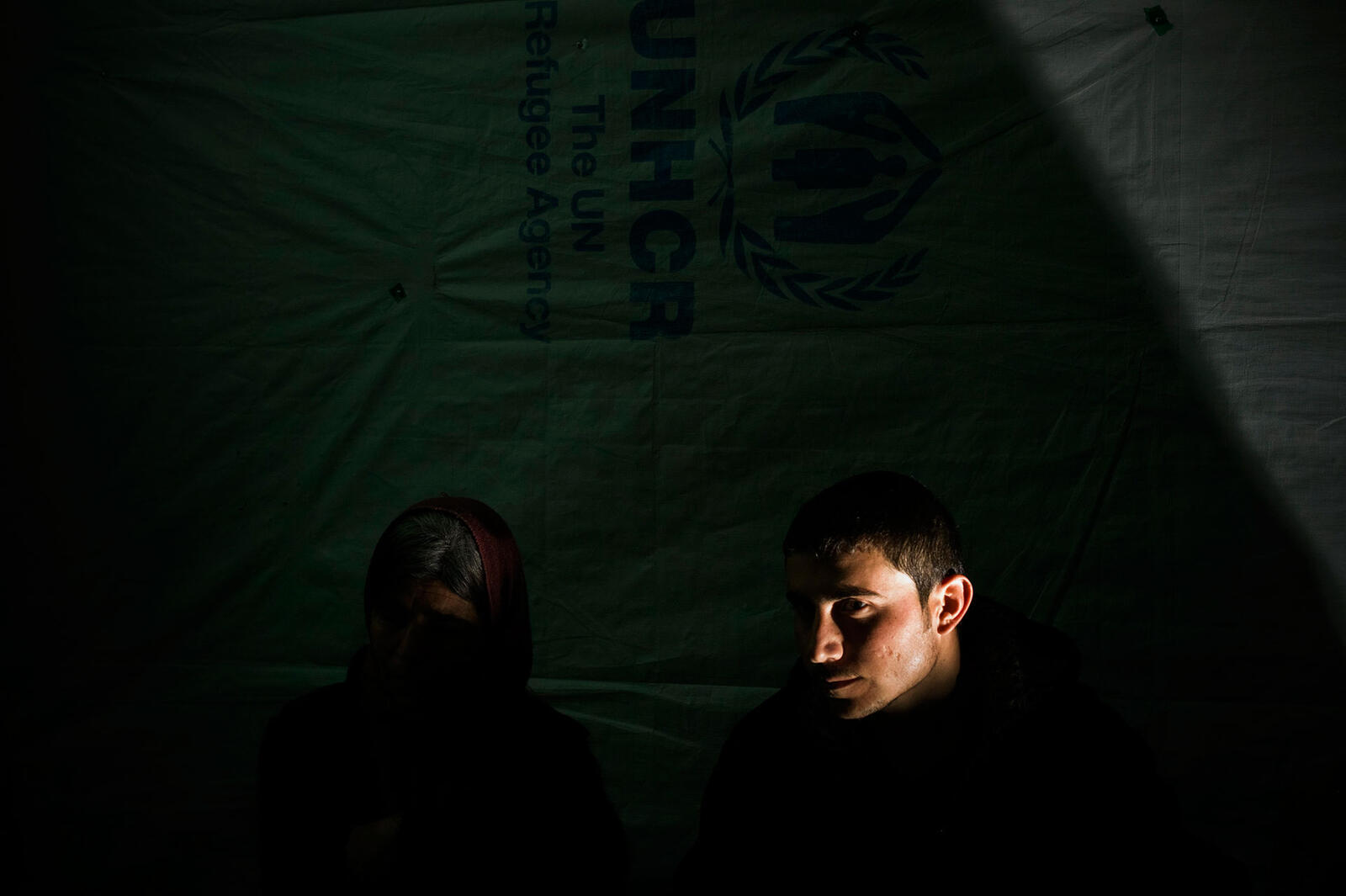

Later I visit Omar, a 22-year-old Yazidi boy, at the unfinished building in Al Qosh where he is sheltering with some of his relatives. He was working in Sulaymaniyah, the second-largest city in Iraq's Kurdish region, when insurgents attacked his village near Sinjar in August 2014. Today, he has no idea where the rest of his family members are.

"How much longer do you think the world will watch as we are killed and our women are enslaved?"

"How much longer do you think this will go on for?" he asks me, sadly. "How much longer do you think the world will watch as we are killed and our women are enslaved?"

His words will ring forever in my ears.

Two men carry the blankets and mattress used by a group of 196 internally displaced people from the Yazidi religious community following their release by militants.

Omar, Sherine, Murad and thousands of other are safe now. But their nightmare is far from over. Many of them have had family members brutally murdered, while others still wait in hope that their imprisoned relatives will one day be released. The impact on these people goes far beyond the bruises on their bodies and scars on their faces.

Aid agencies and local authorities have an enormous responsibility to address their trauma and psychological suffering. Focus group discussions with internally displaced people living in camps and urban areas reveal that many women and girls – mainly from Yazidis communities – are still missing. Often, they have suffered inexplicable abuse.

Local NGOs and UN agencies, including UNHCR, have introduced a number of activities to support victims and survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. But much more still needs to be done. Local institutions need international support to meet these growing needs. Without it, I fear, we will all be asking ourselves in a few years: Why did the international community fail to help these people?