UNHCR increases efforts to help displaced people in Colombia's cities

UNHCR increases efforts to help displaced people in Colombia's cities

The signing of the Agreement of Wills in Soacha was attended by mayoral candidates and representatives of the government and UNHCR. The agreement commits the elected mayor to increase assistance to and protection of displaced people.

BOGOTA, Colombia, April 14 (UNHCR) - It's rare for all candidates in an election campaign to take the same stand on something, but when it comes to the issue of internally displaced people in urban Colombia, their vote is unanimous: Improve protection and access to public services.

On Wednesday, all nine candidates vying to be the mayor of Soacha municipality, near the capital Bogota, signed an Agreement of Wills with UNHCR, stating that whoever wins the election on Sunday will increase efforts to guarantee access for internally displaced persons (IDPs) to health care, education, and protection for their leaders.

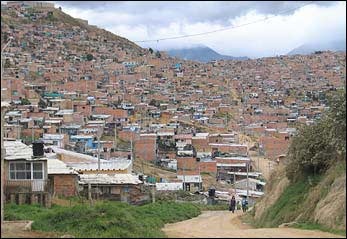

Soacha is among the poorest areas in Colombia with one of the highest concentrations of IDPs who fled their homes over decades of conflict in the country. In fact, studies by the Colombian government show that more than 1 million IDPs live in 10 major cities, more than half of them in just five capitals: Bogota, Cali, Medellín, Barranquilla and Bucaramanga. Thousands more live in smaller adjacent towns, where it is easier to settle for economic and social reasons. Different polls show that few of these IDPs are willing to go back to their original homes.

Unfortunately, thousands of displaced families that fled to the cities, some more than a decade ago, have been unable to integrate into their host communities, to enjoy access to public services or to regain the rights they lost when they were forcibly driven from their homes.

"Even worse, it is not infrequent that displaced persons go to the cities seeking protection, and instead, find the same armed groups whose actions made them fear losing their lives, not to mention criminal gangs of all kinds," said Roberto Meier, UNHCR Representative in Colombia. He added that it was a huge challenge to keep the displaced people from becoming more vulnerable in these circumstances.

A recent report by the Ombudsman's Office revealed that illegal armed groups have been responsible for various displacements in different areas of the cities, a phenomenon known as "intra-urban displacement".

Since it began operations in Colombia in 1997, UNHCR has been actively helping IDPs in the main cities. For several years, the agency has been implementing initiatives to encourage the integration of young IDPs into host communities, as well as projects offering them alternatives to the violence that dominates their environment, in cities like Barrancabermeja, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Mocoa, Quibdó and Soacha. Today, urban IDPs constitute most of the over 30,000 boys and girls who benefit from the Childhood Pedagogy and Protection project implemented by UNHCR's counterpart, Corporación Opción Legal, to guarantee the integration of IDP children in schools.

To enhance the protection of IDPs and populations at risk in the cities, UNHCR in 2004 began to promote a comprehensive and coordinated response to the humanitarian crisis they face, stressing the need for long-term initiatives involving local and national authorities.

As part of this strategy, the refugee agency promoted the opening of a United Nations office in Soacha in January this year, and started regular UNHCR presence in Bucaramanga in the west of the country.

The newer elements in UNHCR's strategy seek to increase and diversify its impact. One of them is the Agreement of Wills. With Wednesday's signing, Soacha's mayoral candidates joined 13 mayors of IDP-hosting cities who signed the agreement in July last year.

"UNHCR has proved to be an ally, but it demands that initiatives come from the communities," noted a non-governmental organisation representative at the signing ceremony in Soacha.

Thousands of internally displaced people live in big Colombian cities and their surroundings, like Soacha on the outskirts of Bogota.

The refugee agency has worked to strengthen the capacity of civil society - including IDP associations, youth, indigenous, Afro-Colombian and women's organisations - to defend their rights, particularly the right to participate in public life and in the formulation of appropriate responses to problems ranging from HIV/AIDS to the need for housing, the prevention of violence against women, and the protection of ethnic minorities who are more vulnerable in urban contexts. Through joint efforts with various universities, UNHCR is also providing free specialist legal advice to the displaced population.

This multifaceted approach seems to be working. "Until UNHCR came here, we felt pretty much alone," said Patricia (not her real name), a young IDP attending Wednesday's ceremony in Soacha. "Now, I know things are not going to change overnight, but we feel that we will be able to mitigate our needs. Having UNHCR here is like having a friend beside us."

By Gustavo Valdivieso

UNHCR Colombia