"You can't imagine what we've been through," says Darfur refugee

"You can't imagine what we've been through," says Darfur refugee

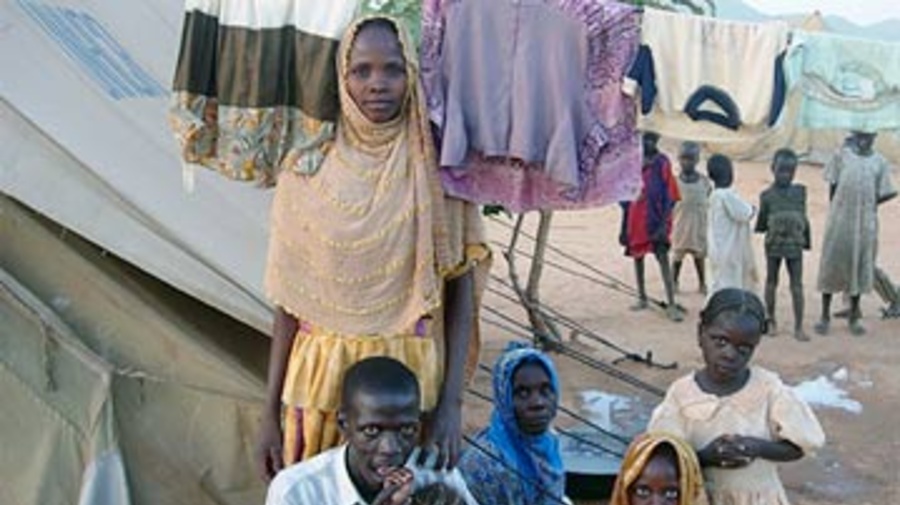

Moussa Hassan Issakh and his family in front of their tent at Djabal camp in eastern Chad.

GOZ BEIDA, Chad (UNHCR) - Sitting cross-legged on a mat in the shadow of a makeshift straw shelter, he told his story in bursts of rapid-fire sentences, waving his hands and arms, his eyes reliving the abysmal events that led him and his family to Djabal camp on the outskirts of this village in eastern Chad.

Moussa Hassan Issakh is a diminutive man, but he exudes a sense of energy and confidence as the leader of Sudanese refugees belonging to the Fur ethnic group in Djabal camp.

In a long series of interviews, Hassan provided a detailed, coherent picture of what happened to him and his family when the Janjaweed, supported by Sudanese planes and troops, descended on his native village of Bindis in August 2004.

"It was going to rain," he recalled, "so we decided to have lunch earlier than usual. My wife was quickly gathering the laundry as the dark clouds approached when I asked her to serve tea."

Hassan, two of his three daughters, his father and his older brother were eating when they heard what seemed like the sounds of an exploding mortar that turned out to be a bomb from one of the notorious Antonov aircraft that he and other refugees say frequently announced the start of a raid on the straw hut villages of West Darfur.

"We went outside to try and find out what it was when we saw men in vehicles that were shooting," he said through an interpreter. "The Janjaweed followed on horses, about 2,000 of them, shooting in all directions. When I stepped outside my hut, I saw a dead man in front of the door."

"The villagers began running in all directions," he added. "I ran to my mother's house to pick up my third daughter. Once inside the house, I saw the second of many dead bodies I would see that day, that of my cousin. I picked up my daughter and ran back to my house to tell the family to hide, but they had already gone."

When he went outside again with his daughter in his arms, he ran into a village woman. "She told me to give her the child and run because if the Janjaweed saw me they would kill us immediately," Hassan said. He handed over the child and ran for his life.

The Janjaweed were everywhere, killing to grab people's bags they thought contained valuables, pillaging the town's market, shooting indiscriminately. Most of the townspeople ran to hide in the fields and gardens that surrounded the town. It had started to rain.

While most of the Janjaweed were at the market, Hassan was able to run in one direction, only to change course when he saw six or seven people dead on the road he was travelling. He was finally able to hide in a nearby field. After the attack, he made his way to the town of Mukdjar, 30 km to the east of Bindis, hiding from the Janjaweed, trying to protect himself from the torrential rains, eating nothing during the two-day walk. He did not know whether his family was dead or alive.

Then luck struck. Upon arriving in Mukdjar, he found his wife, three children and mother and father there. They had reached the town quickly because the Janjaweed, Hassan said, were not interested in killing women, older people or baby girls. Hassan said 48,000 people in all escaped to Mukdjar from Bindis and the surrounding area.

Once in the city, a regional commercial centre, the families gathered to count their dead from the attack on Bindis - about 450 people had been killed as they fled, he claimed. "We did not want to go to Mukdjar because there is a military base there and the Janjaweed frequently came to get munitions," he said. "The Arabs openly bought weapons and ammunition in the market."

But with the Janjaweed surrounding the town, they had no choice but to stay and hide. The Janjaweed had accomplices inside the city, and frequently the Africans were denounced, hunted down, and killed, Hassan said.

He and his family remained in Mukdjar for four months, until the end of the rains. It was impossible to try to flee to Chad because the roads were cut off and the seasonal river beds known as wadis were impassable. The Janjaweed were everywhere. "I was like a prisoner, I could not go out 500 metres from the house," Hassan recalled.

During those months, he and his family, along with the thousands of others who had fled, survived through the generosity of the locals. At night, the women would walk 5-6 km to get grain from small silos and water from a nearby wadi. Throughout this period, the Janjaweed continued to kill inside the town. Finally, when the rains ended, he left his family behind and started the 75-km trek to Chad. "It was every man for himself," Hassan said.

Travelling only at night, he reached the border village of Dagesa. There he found another Sudanese refugee who lent him money so his family could join him. Along with a letter, he sent the money with a Chadian merchant going to Darfur. Hassan waited in Dagesa for several days, hoping his family was still alive. They began arriving by truck a few days later, first his wife with their three daughters, then one week later his sister with her five children. But his mother and father remained in Sudan. "I have no news of them," he said.

The family finally made its way to Goz Amir camp, 60 km south-east of Goz Beida. They were later transferred by UNHCR when Djabal camp opened this summer.

For Hassan, the problems in West Darfur are the result of the Arab nomads trying to chase the Africans out of the area. "For 10 years they stole everything we had in order to weaken us," he said.

Asked if he wanted to return to his home, he shook his head and waved his arms. "No, no, no," he said emphatically. "We are going to remain here until the problems in Sudan are resolved. We can never go back as long as the current government is in power."

"We have spoken together for a long time," he said at the end, "but you can never understand what we have gone through."

By Eduardo Cue

UNHCR Chad