Refugee teacher seeks to "write" the wrongs

Refugee teacher seeks to "write" the wrongs

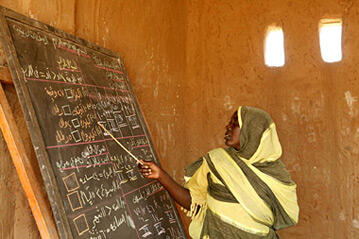

Aziza Souleyman Mahamet teaches an Arabic class in Djabal camp.

DJABAL CAMP, Chad - "I knew how to read and write, that is why I was selected to be a teacher in Djabal camp," says Aziza Souleyman Mahamet. A modest claim, but one that reflects the serious lack of trained and qualified teachers in the schools of eastern Chad's refugee camps.

Aziza, a 40-year-old mother of three, is herself a refugee from West Darfur. "The Janjaweed attacked us and an Antonov plane bombed us," she recalls. Her family walked for seven days before reaching the border with Chad, where they lived for many months through the rainy season. It was only in mid-2004 that UNHCR found them and brought them to Djabal camp.

In her four years of teaching Arabic, Aziza has met many traumatized children. "You have children who saw their parents being murdered - by gunshot or shrapnel from the bombings," she says. "These children have not forgotten the images, and it impacts a lot the way they learn and remember things. Some have dropped out of school because of it."

Thankfully, various psycho-social programmes in the camp have provided counselling to many children, helping them focus better in class.

But the physical infrastructure is often missing. "Now they are learning while sitting on the sand," says Aziza. "We need tables and chairs for the children to be able to sit." There is also a huge need for more textbooks - on average, there is only one book for three pupils, which is not enough to follow classes and do homework. Basic stationary such as notepads and pens is also in demand.

In addition, the harsh weather conditions in eastern Chad, including sand storms and the rainy season, cause school buildings to deteriorate quickly. "Some parents are afraid to send their children to school because they fear the building will collapse on them," says Aziza. With no glass windows, classrooms are exposed to wind and sand storms.

Teachers are trained by UNHCR, UNICEF and NGOs, but the incentives are weak. "Teachers are not paid enough," says Aziza, who makes 25,000 CFA ($50) monthly. The schools' director earns 40,000 CFA per month, based on local rates.

Still, Aziza would not trade her job for any other. "I thank God that now I can teach children," she says with emotion. "For their future and mine, I hope to be able to return to Darfur, to study for myself and continue to teach in my village."

In the meantime, she continues to encourage parents to send their children to school so that when it is safe to return to Darfur, "they will have knowledge and education to rebuild the region."