Q&A: Dinka from Down Under keeps spotlight on Sudan

Q&A: Dinka from Down Under keeps spotlight on Sudan

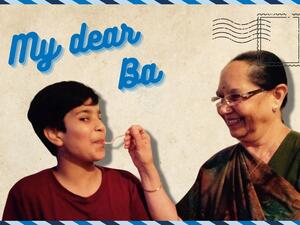

Aguil de'Chut (left) of the Sudanese Australian International Activists Group at the UNHCR ExCom meeting with fellow resettled refugee Nava Malula of the Australia-based Women's Advocacy Unit.

GENEVA, November 23 (UNHCR) - At more than 1.8 metres tall and always clad in something striking, Aguil de'Chut Deng stands out in a crowd. The ethnic Dinka made a big impression during UNHCR's annual ExCom meeting in October, where she presented the NGO statement to the general debate. During the civil war in South Sudan, Aguil spent time in the bush before seeking shelter in a refugee camp in Ethiopia. She was taken in the early 1990s for medical treatment in Kenya, where she was accepted for resettlement in Australia in 1996. She now runs an aid and advocacy group in Canberra on behalf of her compatriots. Deng spoke to Web Editors Haude Morel and Leo Dobbs about her life and work: Excerpts from the interview:

Where do you originally come from?

I'm from Sudan, from the south. I was born in Malakal, Upper Nile state. I went to Australia with my extended family of 11 members in 1996 as a refugee under the government's humanitarian programme.

Why did you leave South Sudan?

I became a refugee because I opposed what the government [in Khartoum] was doing.... I was very angry about the way that the government was treating my people.

Tell us a bit about your early life

My father was a doctor. He worked in the north. We had a very wonderful life, an easy life, in the north, but we had a difficult life in the south.... My father was well informed about what was happening. He used to talk about war breaking out and people getting killed, which at the time I could not imagine happening.

When the war started in 1983 my father was immediately killed and I decided to do whatever I could to make a change.... I joined the SPLM/A, which is the Sudanese People's Liberation Movement/Army, back in 1984. I was given various [medical, nursing and hospitality] tasks.

And what happened when the fighting escalated?

Me and my [female] friends had to train ourselves on how to defend ourselves in case of attack. When all this was happening, I was also taking care of my extended family. The children tended to learn very quickly to adapt to the situation. If you hear a gun, first thing is to stop, don't go anywhere, listen carefully what direction the fire is coming from. You have to learn to know when it is an accident or an attack.... You have to know when the enemy is around.... To move from one place to another is very difficult. You have to be dynamic and adapt to the situation.

Why did you seek shelter in refugee camps?

I thought that now the children [in my extended family] are growing up, what am I going to do with them. And then I realized that I had to take them to school. I heard there were United Nations camps where the children can get an education. So we decided to take them to a refugee camp [at Itang in Ethiopia].

We created women's' groups ... and then we start buying stationery for the children, which was one of our main interests. Then making sure that their nutrition was sufficient, making sure that they had clothes ... ensuring that they had pencil and paper to write on while we were busy during the day.

How important is education?

My father used to tell me that in our tribe girls are not allowed to go to school. But he was rebellious - he put us through school, which was a sin to his brothers and everybody else. My mother was also against this.... They had a fight every year because my mum didn't want me to be in school. Education was the light, my father used to tell me, and that is exactly how I saw it.

The reason I took these 22 children to Itang camp was not just to eat or because I could not protect them, but because I could not give them education and I felt that education was a priority.... Education was very, very important.... I don't want to go a day without learning something that can improve my life.

You became very ill while on the run. Tell us a bit about this.

In 1991, when the Ethiopian regime [of President Mengistu Haile Mariam] fell, we had to move from one area to another.... On the way I felt something and then I twisted and I went round and round and fell.... I collapsed again and it felt like my legs had been electrocuted. It happened again and again and I couldn't walk.... I didn't know until I went to Australia that I had a blood clot in my brain.

You later received medical treatment in Nairobi, where you also started learning English. How did you end up in Australia?

I said, if I am dead it is okay, but if I am alive I will learn English to tell the world the way that our people are being killed in South Sudan. My father, my brother and my uncle all died as a result of the war. My grandmother starved to death.... I could not be active in the field, but I wanted the children to have a better life and schooling.... I was offered a scholarship in Israel, but they told me that I could only take my nuclear children, so I declined.

Two years later, I was told that Australia could offer education to me and my family. But when I went to the interview, this man told me Australia does not take extended family. I said if that was the case then I am not going. And he looked at me and he said, "Why?" I said, "Where do I leave them? These are my children. My children are not better than them, they are not better than my children, so I don't see any child who is better than the other child and I cannot leave anybody.... I will suffer with them in Kenya." And he looked at me and he said: "Okay, we will take all of them."

You helped found the Sudanese Australian International Activist Group. Tell us about this and your work since arriving in Australia.

When I went to Australia in 1996, many people did not know where Sudan was. They didn't know that people were dying there every day. I watched the news and they talked about Israel and Palestine. People were being killed then in southern Sudan. I tried to educate myself, so I bought [English] tapes so that one day I would be able to let people know where Sudan is and what is happening there.

I got support from a few people, but others thought it was a stupid idea because I had children to look after. But to me, I felt that I had 12 million children in southern Sudan.... I met [other] people committed to humanity.... Through these people, I managed to lobby local government and then the federal government.

I started asking for more refugees to come so that the government of Australia would increase the intake ... and through my campaign with friends such as Bishop George Browning, Kerrie Tucker, Michael Carrel and Pat Vargar, convinced the government to increase the intake from Sudan. But when they come, then the work starts - how to integrate.

I moved from Queensland to Canberra so that I could lobby, through countries interested in Sudan, for peace. I went to the United States, I lobbied in England, I went to Germany. I used my community to send letters to local representatives ... that is when I helped create [in the year 2000] the Sudanese Australian International Activist Group. But it has been tough.

Our first aim is to promote our culture and also to integrate, so that we can be part of Australia. But we also want to inform the Australian public about what is happening in Sudan, to condemn human rights violations and to network with other groups internationally so that we can bring peace to Sudan.

Around Australia, but especially in Canberra, we help refugees with such things as settlement services and finding work and we offer translation and interpretation services for free.

The Australian government has cut the African refugee intake and said no more applications from Africans would be considered until July 2008. It cited failure to integrate as one reason. What do you say to that?

This government has done good work [in the past] by increasing refugee intake from Africa.... But recent comments [by Immigration Minister Kevin Andrews about cutting the intake] will be seen as discriminatory and we don't want to see a civilized country like Australia go backwards and discriminate against people. The government needs to restrategize their services to see ... how we can provide better services so that integration will be a quicker process.

In the last 10 years, I know that the services I have provided [to resettled Sudanese] helped them to integrate and also to be good citizens.... I sponsor a lot of children, some of whom have finished university, and I am very proud of them ... they have made a difference to themselves and to the Australian government and, maybe in the future, to the world.

I think today, with fighting in Darfur, the government's priority should be for protection and to increase the intake of the Sudanese.... They [the government] have to get engaged with the people on the ground who are working [with resettled Sudanese] so that they can come up with a new strategy on how they can assist and provide more assistance.