You either have it or you don’t. In any event it will make a big difference to your life. I am talking about your legal—and, by implication, your digital—identity.

Somewhere, a farmer tries to reach the market but at a police checkpoint he cannot produce an ID card. If he is lucky, he might be waved through but, if not, he may face an ID check at a police station or even insults, extortion or beatings. Not far from the checkpoint, a widow cannot inherit land from her deceased husband because her marriage was never registered and she has no marriage certificate. Elsewhere, a refugee cannot buy a SIM card from a local vendor because his UNHCR–issued documentation is not recognized as a token to prove his identity. As a result he is blocked from communicating with his family at home, sending money or accessing the internet.

A couple of hours away, but this time by plane, a stressed urban professional is struggling to manage her identity. Each new service provider or authority that she deals with demands new usernames, passwords and two factor authentications. They have proliferated to an unmanageable state so she has downloaded an app on her smartphone that is designed to manage her PIN numbers and codes. In her handbag there is not only an ID card and a driving license but also several wallets full of smartcards, each seeking to be smarter than the last.

The farmer and the urban professional live on two very different sides of the identity divide and they would rarely, if ever, meet in person. Indeed people without legal identity—and the World Bank reckons they number more than 1 billion worldwide— face increased protection risks and socio-economic exclusion. Refugees in particular are thrown into new environments that are difficult to navigate, and often have no identity documentation or are unable to authenticate the identity documents that they do possess.

Identity: A Sustainable Development Goal

The international community has pledged to provide a legal identity to all by 2030. SDG Target 16.9 is aimed at the situation of more than one billion persons who cannot present proof of their identity. But who takes care of the tens of millions of refugees, forcibly displaced and stateless persons who either cannot safely approach their government, or have no government that recognizes them as citizens? And how can identity management be organized in critical protection situations where your identity being known by the wrong people can be just as dangerous as having no recognized identity at all?

In October 2017, Filippo Grandi, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees announced: “We want every refugee to have a unique digital identity. This will enhance accountability and facilitate two-way communication between refugees and service providers. It will also help prevent and reduce statelessness.”

As part of our reflections on how the High Commissioner’s vision can be implemented a new concept has emerged: Portable User-Centric Identity Management, which is sometimes referred to as self-sovereign identity management. Conceptually, such a system enables any individual to have a private, secure, and self-controlled digital identity. It would allow individuals to identify themselves where needed and gain access to entitlements, such as humanitarian relief, government as well as financial services, education, e-commerce, and communications. A self-sovereign system is a repository of evidence of identity from a range of different sources and issuing authorities. Accordingly, such a system is not tied to any single government or identity authority.

Identity is basically a question about mutual trust: are you indeed the person you claim to be? And, the question (posed in return): is it safe for me to reveal to you who I am? In human history this issue has been dealt with differently and depending on place and context. In most cases however, individuals have been identified with the larger group; as the “son/daughter of” someone, the member of a clan, a religious congregation, or other social group. Within these groups, rules of trust (an oath of allegiance for example) and interaction were established. The group would vouch for its member to outsiders. Standardized documentary IDs are a very recent invention: they were introduced in most countries during the 20th century, often in the context of war. In some countries, to this day, there are none or the systems are voluntary.

However, in most jurisdictions, there is a link between the issuance of IDs and citizenship as only nationals entitled to obtain such documents and foreigners are excluded. There have also been examples where IDs and passes were used for discriminatory purposes, with certain documents imposed on parts of the population with the objectives of stigmatization, discrimination and control. Today, with increased global mobility and States delivering services, the legitimacy of State sponsored ID systems is largely beyond doubt, including for refugees, the forcibly displaced and the stateless.

Identity, Space, and Uses

The ever-increasing space in which human interaction takes place drives the need for establishing more robust systems of trust and identification. In that respect, cyberspace is just an extension of the physical space to which humankind was confined before. The internet is not only a rather recent invention but its development was left by and large to the private sector and non-state entities. Hence, internet actors have developed their own identification, verification and authentication methods based on usernames, passwords, biometric images that are sometimes, but not necessarily, linked to state issued ID documents. For this reason, people hold multiple identities depending on use cases: a simple password for communication, two factor authentication for online banking, a State issued card with a chip for submitting tax returns, etc. It seems to me that there is nothing wrong with that fragmented digital identity as it allows for a degree of privacy most people appreciate. More controversial are identification attributes that are communicated automatically and without the user’s consent, such as IP addresses and GSM/CDMA cell IDs.

Simple forms of authentication often work on a global scale. In most cases people can access their social network and eMail accounts across borders and while traveling. However, authentication may not be the only barrier to online access. A further example is where access to digital services or content may be restricted on the basis of the user’s geographical location, regardless of an individual’s ability to authenticate their identity. Private sector companies may be limited by the ownership of exclusive territorial rights, while government regulators may have been purposely established under the law to control what can be accessed, published, or viewed online and by whom or even to suppress information.

In this complex environment UNHCR could consider assuming a new and important role: namely, facilitating a recognized identity, both legal and digital, for refugees and other forcibly displaced persons, which is effective across countries, organizations and contexts for as many use cases as possible and thereby bridging the incompatibilities between different identity regimes and trust systems.

Registration, Identification, and Levels of Trust

Currently, States are in the process of establishing new regulatory frameworks to oversee electronic identification and trust services for online access and electronic transactions. The limitation here is that a legal identity issued by one State may not be recognized by another. At the same time, the private sector and tech companies are experimenting with portable ID wallets on smart phones, often based on blockchain technology. The limitation that these innovations face is that, while functional identities issued by the private sector may be recognized for commercial purposes, they often lack legal recognition. That said, new regulations on electronic signatures, electronic transactions, the involved bodies and standard processes for providing safe ways for users to conduct business online (such as financial transfers), assign digital and paper transactions the same legal standing.

For the UN Refugee Agency to attempt to bridge the identity divide for refugees and other persons of concern in this evolving context, it would have to go beyond the simple registration of claimed identities and become involved in identity assurance, potentially in the context of federated and user-centric identity management systems. If requested by refugees and other persons of concern, UNHCR should be willing and able to determine, with some level of certainty, that an identity can be trusted and that an electronic credential representing a person or group of persons (a family for example) can be the basis for specific interactions with authorities and to access certain services.

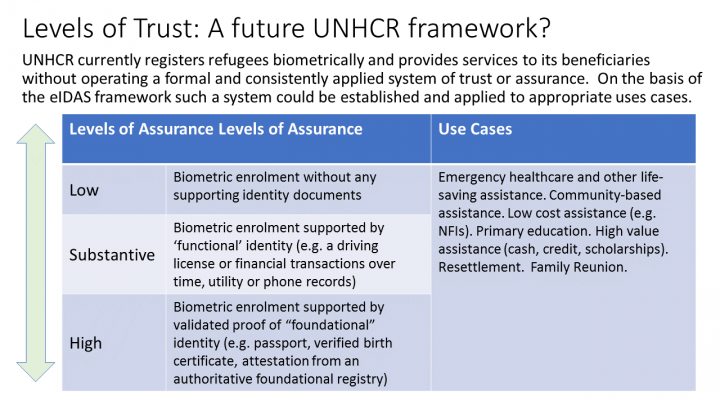

For a refugee, or any other person for that matter, identity assurance is the level at which the credential being presented can be trusted to be a proxy for the individual to whom it was issued, and not a proxy for somebody else. Levels of Trust (or assurance levels) are established for a given credential by measuring the technological reliability of the credential, and the processes and evidence of identity upon which it was generated, against the standards established by regulatory frameworks, policy and accepted practice.

The eIDAS Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 910/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 on electronic identification and trust services for electronic transactions in the internal market) provides an example of how this can work in practice. The Regulation sets out the basis upon which each EU Member can recognize the identification credentials of other Member States, and establishes the assurance levels for electronic identification. These levels are intended to capable of being applied to a range of different identity systems. Additionally, the Regulation also enables the use of electronic signatures and seals by providing assurance of their legal effect, and by allowing qualified organizations to act as ‘trust services providers’.

The assurance levels established by the Regulation are described as follows:

Low: electronic identification which provides limited confidence in the claimed identity and is designed to decrease the risk of misuse or alternation of identities.

Substantial: electronic identification which provides substantial confidence, and is designed to substantially reduce the risk of misuse or alternation of identities;

High: electronic identification which provides the highest degree of confidence and which is designed to prevent misuse or alternation of the identity.

The eIDAS framework links digital identity with registration and the availability of identity papers and, thus, digital with legal identity. It provides the opportunity to reflect on how UNHCR could certify and upload into digital wallets copies of ID documents issued on paper, and set-up a digital public notary service for refugees. Another issue to be considered is the relationship between levels of trust and use cases: most likely not all services delivered to refugees and other forcibly displaced persons require the same level of trust. While all refugees are entitled to the rights established in the 1951 Convention and in international human rights law, many services either go beyond those rights or refugees are required to satisfy regulatory requirements are, such as the ‘know your customer’ requirements to set up bank accounts.

Conclusion

Portable and user-centric (or self-sovereign) identity management systems may enable any individual to have a private, secure, and self-controlled digital identity. For refugees in particular, the value of such a system will depend, to a large extent, on the cross-border recognition of that identity. Hence, facilitating a unique digital identity for every refugee, as envisioned by the High Commissioner, will require new services to certify identity in line with international standards within a regulatory framework which is still to be developed. Ultimately, facilitating digital inclusion in the context of forced displacement and statelessness may require the UN Refugee Agency to get involved in identity and trust assurance.

Both for today and tomorrow, empowerment will be achieved through digital inclusion and trust management. Technology is a great enabler for access to jobs, income and remittances as well as online learning and web-based economic activities. User-centric identity management appears as the solution to provide effective digital inclusion and overcome the glaring identity divide, thus making a difference in the lives of people who will otherwise remain invisible and excluded.