By Milton Moreno, UNHCR Representative for Costa Rica, Craig Loschmann, Economist, UNHCR Americas, and Theresa Beltramo, Senior Economist, UNHCR

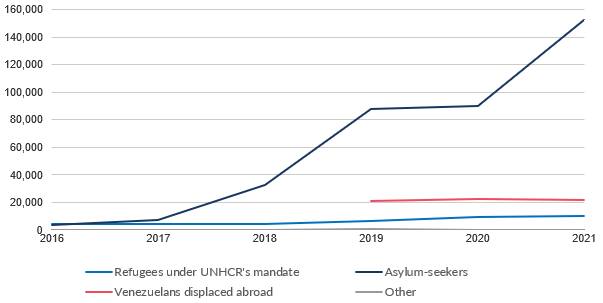

In Costa Rica, the negative impacts of the pandemic continue to ripple through the economy – even as it partially recovers from 2020, when the country saw its sharpest economic contraction in decades resulting in high unemployment and rising poverty (World Bank, 2021). Nonetheless, through the pandemic, the country continues to offer asylum to those in need of international protection, welcoming the highest number of asylum seekers, refugees and other displaced persons in 30 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Persons of concern to UNHCR in Costa Rica

The rapid rise in the number of persons of concern to UNHCR in Costa Rica – today equivalent to 3% of the national population – comes at a cost. It has strained the government’s capacity to receive and process cases, and delayed the delivery of documentation and work permits for asylum-seekers, particularly in the Northern area bordering Nicaragua. The national systems for education, health, social protection and legal assistance are also stretched. The result is displaced individuals face more challenges than ever before in fully integrating into the labour market, supporting themselves to meet basic needs, and contributing to the local economy.

While UNHCR has stepped up its assistance and response to the pandemic in the near term, looking forward to medium-term solutions, these challenges highlight the importance for taking an area-based development approach in Costa Rica founded on deeper links between humanitarian and development response. Doing so will improve the lives of displaced populations as well as that of host communities by building individual resilience and institutional capacities. An area-based approach is particularly needed in the North, where most Nicaraguans continue to enter Costa Rica in increasing numbers and investments are needed in the local health and education infrastructure. Jobs and livelihoods interventions as well as private sector development are also much needed to create an enabling environment and new opportunities.

Exactly what type of support is needed?

UNHCR teamed up with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) to conduct two rounds of a phone survey between March and August 2021 to study the impact of COVID-19 on displaced persons in Costa Rica. The survey was modeled after the World Bank High Frequency Phone Survey conducted in Costa Rica and 70-plus countries globally (World Bank, 2021). While not exhaustive, the survey results affirm operational assessments and provide critical evidence on the areas where programmatic focus should be stepped up: livelihoods, eliminating food insecurity, and strengthening access to essential services.

The three main groups of displaced populations in Costa Rica were represented in the survey, namely Nicaraguans, Venezuelans and Cubans. Where possible, UNHCR’s survey results were compared with those from surveys of Costa Rican nationals conducted by the World Bank in 2020. The comparison with national households is important when considering an area-based approach that emphasizes both displaced populations as well as host communities.

According to UNHCR’s survey, the economic impact of the pandemic has been severe for displaced populations. Even though a considerable share of respondents say they are employed, 75% also report that a household member had lost a job since pandemic-related restrictions were first put into place in March 2020. This reflects the fragility of most households’ livelihood situation during the crisis and underlines the inherent fragility of displaced populations in economic shocks. Moreover, nearly 75% of displaced respondents report less family income compared to pre-COVID times. And despite signs of recovery, financial insecurity remains pronounced in August 2021 as 70% of respondents said they were forced to deplete assets or rely on others to meet daily needs.

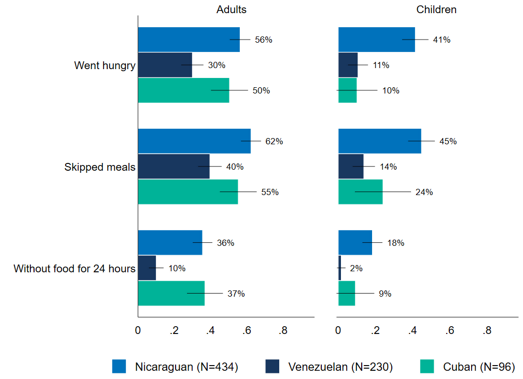

Food insecurity is high with 61% of displaced respondents reporting in August 2021 that an adult in their family skipped a meal in the last week. This rate is far higher than the 12% reported by Costa Ricans in the World Bank survey in 2020. The Nicaraguan population, in particular, faces high levels of food-related vulnerability: 40% of Nicaraguan respondents report a child going hungry in the past 30 days. Despite these prevalent needs, food- and cash-based support to displaced populations fell between March and August 2021.

Figure 2: Food insecurity reported by displaced households in Costa Rica, August 2021

In the area of health services, 45% of displaced respondents say their household needed a medical appointment during the period between the survey rounds, and of those, 13% had to delay or cancel the appointment. This figure is slightly higher than the 5% of national households that were unable to get an appointment in 2020. While there are no clear differences in access to healthcare across the three main displaced groups, Venezuelan respondents are less likely than Cuban and Nicaraguan respondents to believe the government provides healthcare without discrimination.

School closures have been a major disruption for households with school-aged children, though there is little evidence of extensive dropouts. Nearly all children from displaced households remained enrolled in school in August 2021, and of those that have not physically returned, the expectation is that they will do so in the coming year. Nevertheless, the quality of school is perceived to be worse since the pandemic began. Nearly half of all respondents assess the quality of school to be poor or very poor in August 2021, compared to only 15% prior to March 2020. Challenges around remote learning are likely the main reason, especially for Nicaraguan households who report less access to internet and other computer resources such as laptops.

Continue our focus on promotion of self-sufficiency

Achieving self-sufficiency for the population of concern is at the core of the work of UNHCR’s livelihoods and economic inclusion strategy in Costa Rica. The key to self-sufficiency lies in the collaboration between the public and private sector, civil society organizations, and international cooperation. UNHCR Costa Rica prioritizes its facilitator role in the promotion of collaborations between these various stakeholders.

The importance of chronicling the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on displaced populations cannot be understated. The ability to quantify impact allows us to adapt current and future programmes and be more effective at closing gaps in access to health, education, jobs, and food. Importantly, as has been the case in other situations, these data are a solid basis for advocacy with the government. In the case of development partners, the data provide the evidence needed to fund and lead programmes that improve development outcomes for both displaced populations and host communities.

Building on this collaborative survey exercise, we hope that the Government of Costa Rica will consider including forcibly displaced in national statistics exercises going forward to ensure that no one is left behind in our global partnership to monitor and deliver on the SDGs (UN SDGs, 2017).