Feature: Resourceful refugees show "recycling" is not a dirty word

Feature: Resourceful refugees show "recycling" is not a dirty word

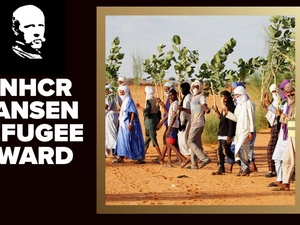

Flashing their plastic are Habibo Ali Malim (centre) and the other founding members of her plastic-recycling handicraft project in Hagadera camp, Dadaab.

DADAAB, Kenya (UNHCR) - Somali refugee Habibo Ali Malim just wanted to keep busy during a meeting with camp officials. But what her industrious hands were doing - transforming discarded plastic shopping bags into woven mats - proved to be the spark for an innovative project that has cleaned up her refugee camp, cut down on disease, and provided a source of income for some 500 families.

As Malim, a mother of seven, recalls, she wanted to make a mat to cover the entrance to a latrine in Hagadera refugee camp (one of three camps in the Dadaab complex in north-eastern Kenya). She feared being molested if she ventured outside Hagadera to gather plant fibre, so she improvised with something readily available inside the camp - old plastic bags cut into strips.

"All Somalis are natural weavers, because our houses are made from sisal and bark from trees woven into mats," says Malim outside the small workshop where her wares are displayed today.

As she sat in the camp meeting quietly weaving her mat - back in 1999 - her unique project caught the attention of a CARE (non-governmental organisation Cooperative for Aid and Relief Everywhere) Kenya official who saw the possibility of starting a handicraft business. The project quickly mushroomed.

"I started this project with just two other people," Malim recalls. "The second week we were 13; the third week, 20. And by the fourth week there were more than 100 people involved." Today the handicraft co-operative has some 522 members divided into 13 groups, who receive training in making decorative items from plastic bags.

In addition to making latrine-door covers (which are bought for the camp by CARE), the groups make colourful vases, baskets and handbags, and have branched out into weaving cloth on a loom as well. Abdi Sheikh Osman, the project leader on behalf of CARE Kenya, is looking for markets for the refugees' products in Kenya and beyond.

Malim is astonished at what she created: "The aim of this project was just to clean up the environment, then to get a strong cover for the latrines, and thirdly, to get some income."

In a recent month, Malim and the members of her group earned about 1,800 Kenyan shillings ($23) - not a lot in dollar terms, but a substantial sum in a refugee camp where fights can break out over one shilling.

"I am very happy to get some income," says Malim. "I can buy books and shoes for my children." She adds shyly that because of the project, "I have become a prominent person in the camp." A man who has joined Malim's group, Abdi Mohamed Awid, says he is able to provide his family with vegetables and meat that are not included in the camp rations, as well as clothing bought with his income from weaving.

The project has also cut down on disease in the camp, since the plastic bags that used to litter the landscape provided fertile breeding grounds for mosquitoes. In addition, animals used to die after eating these bags, and their rotting carcasses contributed to the spread of disease.

The project has been so successful in improving the appearance of the camp that the police chief of the nearest large town, Garissa, reportedly suggested the Hagadera group come to his town to gather up the ubiquitous plastic bags littering the ground there.

But thanks to the refugees of Hagadera, recycling is no longer a dirty word. In fact, the way the project is catching on, they could soon be chanting an unlikely refrain - Plastic, don't leave home without it.

By Kitty McKinsey

UNHCR Regional Office in Nairobi