It was something Natalia Nahra had noticed at every turn of her career. When people had trouble accessing good information, they struggled to make the best choices. It was true in the United States where she had practiced law; average employees strained to understand what their rights were, what they were entitled to and how to protect themselves in the workplace. It was just as true in villages in Southeast Asia where she had worked to combat human trafficking. There, families sometimes sent young girls to bigger cities alone or with a relative, seemingly unaware of how susceptible they were to being exploited.

“What I remember thinking at that time…was if only we can figure out how to get information to people so that they can at least decide if it’s worth it,” Nahra says. “I noticed in general, access to information is always a challenge no matter what kind of work you’re doing.”

That held true for asylum seekers, too. After Nahra transitioned to a career with UNHCR, she realized a lack of access to information was a key obstacle facing refugees in Israel.

The majority of asylum seekers in that country are Eritrean, and although many of the 32,000 of them do learn to speak Hebrew, the majority cannot read it. Nevertheless, information for refugees was largely available in English or Hebrew, only sometimes Tigrinya. And much of it was only available on Facebook, or in person at various organizations. The problem manifested itself in refugees going from organization to organization when they needed to ask a question or resolve a problem, waiting to be seen and then being turned away and sent to another agency better positioned to help them. Nahra says it was incredibly frustrating for them.

On top of that, “information such as reception hours for various organizations, available livelihoods or adult learning opportunities, new laws and policies can literally change from day to day,” she says.

Information needed constant updating, and constant translation, in a language and mode refugees could access and understand.

Many ideas, many limitations

Nahra did have something working in her favor. She had already been selected as a 2016 UNHCR Innovation Fellow. These competitively selected Fellows define a unique challenge and develop, test, and prototype a solution to address it using human-centered design and some funding.

But at the time she was selected as a Fellow, Nahra was still based in Baku, Azerbaijan, working on IDP issues. She moved to Israel in March, a few months behind the other Innovation Fellows when it came to finding a project to work on.

Fortunately, hers was not the only mind at work on issues surrounding communication with refugees. Emily Primack, who worked at a community-based organization in Israel, and Sari Cohen, a longtime volunteer and graphic designer, had been talking about developing a smartphone app aimed at getting information to Israel’s refugee population.

“I was really aware that I was new in the context,” Nahra says. “I didn’t want to impose the requirements of the Fellowship on them and it was their idea and their concept.” Fellows are required to follow the set innovation process and approaches. “But as we met and discussed their ideas, I explained the stages of the Fellowship and the human-centered design process and asked if they’d be willing to take a few steps back and see if their smartphone app was the smartest solution for the problem. They agreed.”

Primack, Cohen, and Nahra examined which sources of news people trusted, and how they used smartphones. The team also wanted to be able to invite young Israeli professionals to think about this problem, and to make it an outreach opportunity. So they set up a meeting and invited communication strategy consultants, journalists, an industrial designer, a social entrepreneur, a technology developer and a Sudanese woman seeking asylum who was often a community liaison for local NGOs.

The outcome was just what Nahra and her partners had hoped for. “We informed them of the situation, they asked a lot of questions, they came up with wild ideas,” she said.

Natalia’s ideation workshop in Tel Aviv to brainstorm possible solutions to her challenge.

To ensure they weren’t blindly relying on technology, or ignoring community-rooted concepts that might not have jumped out to outsiders, the group started by brainstorming ideas that could have been used 100 years ago. Unfortunately, given the extremely restrictive environment for refugees in Israel—men can be held in a remote detention facility called Holot for up to a year—few ideas were practicable.

But a hard look at the realities of refugee life in Israel gave Nahra and her colleagues, even more, the conviction that a smartphone app that delivered reliable information to users would be of huge benefit. Men who leave Holot before their terms are over are vulnerable to further detention, so delivering information straight to them was key. When Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers finish their mandated terms in Holot, they must still adhere to strict rules on where refugees may settle, what work they can do and how to access services.

In other words, there was a lot of critical information to relay. Furthermore, it was information not many refugees had. UNHCR-led focus groups that asked refugees what they needed to know for life after Holot showed many didn’t really understand what they faced after leaving the facility.

The solution had to be a sustainable and community-based platform that amplified available information and didn’t impose an unrealistic burden on the organizations that would need to coordinate its upkeep.

Primed for inclusion

Nahra had initially eschewed the idea of creating a smartphone app because everyone else seemed to be doing exactly that. But once she took stock of the constraints, the needs and the context, she realized it was one of the only solutions that could really work.

Only about 10 percent of asylum seekers in Israel have access to a computer, but 90 percent of them have smartphones, including women and those who cannot read.

Nahra, Primack and Cohen set out to create an app that would help unburden refugees in Israel from going organization to organization in search of answers, and to try to reach those who reside in remote periphery areas around the country.

Because Primack and Cohen hadn’t gone through any innovation training, Nahra basically took them through the process she had just learned through her Fellowship workshop. She led them through retreats, exercises and strategic planning sessions. They enrolled in a design thinking workshop and started testing like crazy, getting more data and then iterating. The team went to various reception centers and detention facilities to try their prototype out on refugees and colleagues.

“Our first prototypes had more branches to the trees and you had to be able to organize information categorically in a way that was typically Western,” says Nahra.

They brought out paper models and asked asylum seekers to pretend the sheets were their cell phone screens, testing out the logic and the navigation. They asked men, women and youth in various locations to show them their best friends on Facebook, and watched how they navigated through the app to find them.

By observing refugees interact with their smartphones, the three noticed they were mostly using scrolling on apps like Facebook to find what they were looking for, not other tools like the search bar. They also noticed that often questions were interlinked within multiple categories, and end users organized their questions under different categories than the one they had chosen.

Because of their backgrounds in child protection and sexual and gender-based violence and social work and community-based organizations, the three were accustomed to working with the most desperate people. Nahra says they were constantly attuned to think about and test how women would use it, how Sudanese would use it, disabled people, etc.

“This is who we see on a normal, everyday basis when we’re at work,” Nahra says. “All of us were already primed. The inclusion of age, gender, diversity in protection approach was already ingrained in all of us.”

The power of three was working to their advantage, too. Primack had excellent access to local refugee communities and area NGOs and knew how things worked. Cohen brought in the design component and was familiar with the needs of clients that would come to the two social work NGOs she volunteered with. “Between the three of us we really thought differently and had discussions around things and wouldn’t always agree,” Nahra says.

At some point, they realized enough was enough. It was time to take the information they’d collected and build the product. After the Fellowship funding came through, they only had two months to do so.

Rapid progress on an urgent need

Neither Nahra nor either of her collaborators had developed an app before, and they wanted to engage the talented local Israeli technology community on reaching out to the refugees in their midst. So the team wrote up a Request for Proposals and sent it out locally.

They responses they got were disappointing: they didn’t have enough money to pay developers for even a basic app. “We really had no idea how much everything cost,” Nahra remembers. The team was stuck. There was no point using up any of UNHCR’s money if it wasn’t going to actually deliver results.

But Nahra had an idea. She had been in Portugal a few weeks before and went to a “community lunch,” where vendors brought in food for a big meal with local community members. It was a dreary, rainy day so everyone had stayed for hours and hours, learning about the country and each other. Nahra had heard about Portugal’s big tech community and met a local developer whom now she thought of again. She sent him the RFP to see if he knew anyone who could meet its demands within the cost and time limits. Everyone else had been ruled out. And time was almost up.

The day before the deadline, the Portuguese developers came in with a proposal. They were able to do front and back end, iPhone and Android. “It was kind of crazy, and we were like, is this for real?” says Nahra. “It was right under our budget. We went and scheduled the call immediately.”

From there progress was, by necessity, rapid. Cohen used her graphic design skills to create the look of the app, which also was tested with the asylum seekers for their feedback, despite being on maternity leave with a newborn. Primack was working on the project while planning her wedding. And Nahra remembers sometimes spending up to 40 hours a week on it in addition to her regular job with UNHCR. They tested four prototypes.

“We probably moved forward with the project because we had no idea how much time all of this would take,” Nahra says. “Details like navigating through the app. Do you use an ‘X’? Do you just swipe? It was like building a house and having to install every single switch cover, every single doorknob, and all without ever having done it before.”

On top of it all, everything had to be translated into the necessary languages. Arabic, Hebrew and English have shared the open-source code for text-to-speech. “That’s fairly easy, “ Nahra says. “But Tigrinya? It doesn’t exist.” The team had to engage an NGO colleague to record all of the text in bites for each paragraph. And there were more than 300 of them.

An important protection tool

When the app, called Salaam, finally launched in June 2017, the exhausted three barely had the energy to cheer.

“It was exciting and surreal to see the app we’d been working on for so long on our phones,” Nahra says. “But I was anxious … There’s always that second-guessing.”

Nahra and her partners remind themselves of the utility of the app they created. For refugees and even for UNHCR and its NGO partners. The information is reliable. It’s available, without too much navigation, in the four principle languages and in audio form.

The app requires ongoing translation that implementing partners must commit to, one reason Nahra and her colleagues chose an interagency model that keeps UNHCR as the “super-user” and assigns updating duties to each participating organization for information within its niche. For under-resourced, overworked organizations, it’s a big ask.

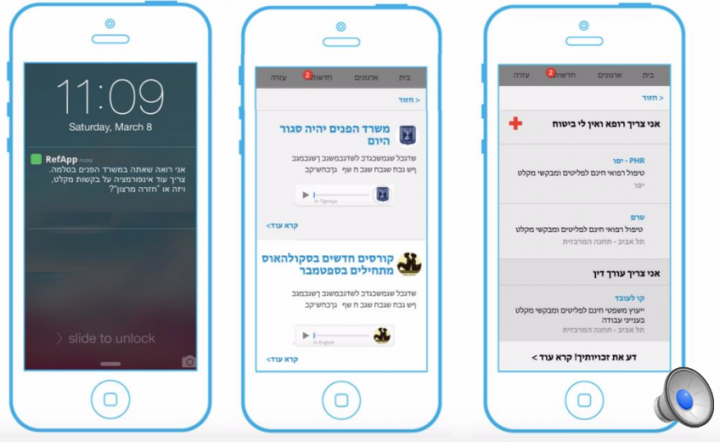

The third iteration of Natalia’s prototype with Hebrew translation.

But the need for accurate and updated information is more pressing than ever. A new law allows the Israeli government to take 20 percent of an asylum seeker’s salary, the return of which will be contingent upon that person leaving the country. Furthermore, it will be important to be able to share information and analysis about a recently decided Supreme Court case involving the state’s voluntary departure program. “Access to correct information is really important because there can be a lot of panic and subsequent rumors that asylum-seekers will base their decisions on,” says Nahra.

Primack was hired by UNHCR as a Senior Program Assistant, where she meets regularly with local Israeli NGOs and has been training local focal points on how to update their pieces of the app with new answers and news alerts. She is able to remain a focal point for the project as the others go their separate ways, Cohen to further education and a design job with a cyber-security company and Nahra to an extended leave outside of Israel.

The three plan to meet up and officially celebrate the app they created in November, when they travel to Lisbon to meet the developers they have yet to see face to face.

“By then we will have a good sense of whether the app is working well, being used, being updated,” says Nahra. She says every time they tested the app with asylum seekers they responded with excitement and positivity about Salaam. They, along with NGO partners, always encouraged the team to keep going. That positive feedback from the end users drove them forward.

“I want to see it succeed because I think it’s really useful to people,” she says. “Having access to accurate and reliable information is so important, particularly when one is displaced and trying to access assistance and make decisions about one’s life, rights, and durable solutions.”

“It’s an important protection tool to be able to say, ‘We see you. And you have the right to have access to information.’”

We’re always looking for great stories, ideas, and opinions on innovations that are led by or create impact for refugees. If you have one to share with us send us an email at [email protected]

If you’d like to repost this article on your website, please see our reposting policy.