Refugees risk all to seek lifeline across Indian Ocean

Refugees risk all to seek lifeline across Indian Ocean

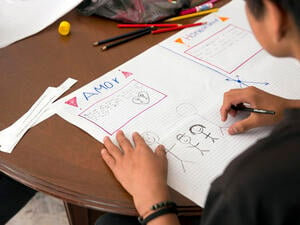

An asylum-seeker at the immigration detention centre in Medan, Indonesia. Many detainees have arrived irregularly by boat.

MEDAN, Indonesia, November 4 (UNHCR) - Their stories are horrific: fleeing persecution on overcrowded boats, stranded at sea with no food, water or hope of reaching safety.

And their numbers are worrying. From January to July, Australia recorded more than 17,000 irregular maritime arrivals. In addition, some reports suggest that in the first eight months of this year, more than 24,000 people left on boats from the Bay of Bengal. UNHCR cannot verify this figure as it has no presence at departure points. Accurate figures are hard to obtain given the clandestine nature of these irregular movements, but collated media reports indicate that more than 400 people in the region have died or gone missing making the journey so far this year.

Yet more people are expected to follow in their wake as the monsoon rains ease across the Indian Ocean. Why do they take these risks and what can be done to prevent further tragedies at sea?

Siva* was an aspiring accountant in eastern Sri Lanka who decided to leave his home after years of harassment and intimidation. Twice he was abducted by unknown men, who wrongly accused him of links to the rebel Tamil Tigers and demanded he hand over weapons he did not have. He escaped to another city, but his captors continued to harass his mother back home.

"I thought if I stayed in the country, I would be killed. So I decided to leave by boat," said the 24-year-old ethnic Tamil. "I didn't care where I went, I just wanted to save my life." He paid some smugglers more than US$2,200 for what they said would be a nine-day voyage to Australia. But Siva and 60 other passengers ended up spending 47 days at sea after their engine failed mid-way.

"We had food and water for the first 15 days. Then we drank sea water and tried to catch fish. Still, two men died and their bodies were thrown into the sea," recalled Siva. "One day a ship passed and hit us, but it did not stop to help. No one expected to reach shore, we thought we would all die." After nearly seven weeks at sea, they were found by fishermen and taken to Sumatra in Indonesia.

Abdul*, 18, took a different but no less difficult route. A Rohingya from northern Rakhine state in Myanmar, he struggled to survive as a farmer and fisherman as he was not allowed to move freely. Despite living there for generations, the Rohingya are not recognized as Myanmar citizens and face many restrictions in their daily lives. These difficulties were exacerbated after the outbreak of inter-communal violence in June 2012, during which Abdul's grandfather was killed.

Abdul and his brother left a year before the violence, on a boat carrying 129 people. "We were looking for any country that was safe, somewhere we could live. We planned to stop the first time we saw land," he said. "We landed in Thailand. We were caught by men in uniform and pushed back to sea."

To stay alive, the passengers rationed what they had left, sipping only half a glass of water a day. On the 18th day of their voyage, a passing fishing boat found and fed them, then towed them to Aceh in northern Indonesia.

Both Siva and Abdul are now in detention in the government-run Belawan immigration detention centre near the Indonesian city of Medan. UNHCR has registered, interviewed and recognized them as refugees. They are due to be released soon to community housing managed by the International Organization for Migration.

Despite the trauma they have been through, both men say they would do it again.

"I don't regret coming because in Sri Lanka, my life was also in danger," said Siva. Abdul echoed, "I don't want to go back to Myanmar, I might get shot."

Concerned about the human toll and suffering surrounding these irregular maritime movements, UNHCR has been calling for a coordinated approach to address the problem through the implementation of the Regional Cooperation Framework that was first endorsed by the Bali Process on People Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime.

"Countries affected by such movements should adopt a comprehensive approach that addresses the root causes of irregular maritime movements and is underpinned by strengthened coordination on search and rescue at sea, interceptions, disembarkation, assistance and identification of outcomes and solutions," said James Lynch, UNHCR's regional coordinator for South-east Asia.

He added, "By agreeing in advance who is responsible for what, when a maritime incident occurs, and how states can share the responsibility for support and solutions after disembarkation, we can mitigate the risks that people face when taking to the seas."

At a regional roundtable on the topic organized by UNHCR and the Indonesian government in March, delegates from 14 countries in the region and beyond discussed proposals including the development of regional guidelines on legal standards relating to disembarkation, and the mapping of post-disembarkation options to ensure that host countries are properly supported.

For the Regional Cooperation Framework to be applied in practice, said Lynch, "countries of origin must urgently address the underlying factors causing people to leave on smugglers' boats, while receiving countries should harmonize conditions of stay for boat arrivals to ensure that they have access to assistance and protection where they are before outcomes can be found."

For Siva, the solution seems simple. "I wasted 24 years of my life because of the problems in my country," said the Sri Lankan refugee. "I would like to study if I have a chance. I must stay alive and live peacefully."

* Names changed for protection reasons

By Vivian Tan in Medan, Indonesia