In their own words

Celebrating, but not feeling celebrated, during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

By Sarah Schafer

24 May 2021

Vimala Phongsavanh and her parents, two Laotian refugees, stand in front of a home they own in Rhode Island. © UNHCR/Robin Winchell

In their own words

Celebrating, but not feeling celebrated, during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage MonthBy Sarah Schafer

24 May 2021

Vimala Phongsavanh and her parents, former Laotian refugees, Kongdeuane and Syphanh. The family stands in front of the Rhode Island home they own. © UNHCR/Robin Winchell

May in the United States is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. The designation, enshrined into law by the US Congress in 1992, recognizes the ways Asian and Pacific Americans have contributed to the country and the development of “the arts, sciences, government, military, commerce, and education.”

But this year, many Asian Americans are not feeling celebrated.

The COVID-19 pandemic – and in particular the anti-Asian rhetoric spread in the early days of the outbreak – helped fuel a rise in discrimination and violence against Asian Americans in the U.S. that has not abated. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, anti-Asian hate crimes across 16 American cities rose 145 per cent in 2020, with the first sharp increase occurring in March and April of that year.

According to a report compiled by the New York Times, Asians in America were spat on, beaten, pepper sprayed and more in the last year. In May, a man shot and killed eight people, six of them women of Asian descent, at three spas in Atlanta, claiming he wanted to remove sexual temptation. The murders prompted widespread and heated discussion on the intersection of sexism and racism.

We spoke to four Asian Americans who come from refugee backgrounds about assimilation and discrimination, memory and forgetting, individual identity and community cohesion, and the complexities of discovering – and asserting – what it means to be American.

Hard Lessons

Sang Rem

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Sang and her family fled Myanmar to a nearby country in 2007. One day, Sang, then 14, and her older sister, left the refugee compound to buy soap at the local market. As soon as they walked outside, men who were waiting grabbed them and took them away.

A month passed before Sang saw her parents again. The men – she did not know whether they were military or police or something else – locked her up. She was then taken to the border, threatened with being sent back to Myanmar and then finally put into the hands of other nameless men who let her call her parents. For a price, they returned her and her sister. Shortly after, the family learned they would be resettled in the United States.

“When we first got [to the U.S.], I was scared of sirens, ambulances, noise, police cars, the lights”

“They gave us numbers. My number was 0-2-7-1-0,” Sang recalled, saying the number in the language of the jailers. “When we first got [to the U.S.], I was scared of sirens, ambulances, noise, police cars, the lights,” she said, apologizing for the fact that she sobs every time she tells the story.

Sang and her siblings on the steps of her home in the village in Myanmar. Sang is in the brown floral dress second from the right. Photo: Courtesy Sang Rem

“I can be a bridge for the community”

Now 28 and a U.S. citizen, Sang is married and working at the Spero Project, an organization that helps newly arrived refugees. It offered her flexible hours and financial support so she could pursue her master’s degree in family and child studies at the University of Central Oklahoma.

“When we moved to Oklahoma City, the founder of the Spero Project … helped me and my cousins and siblings. Our family loves music and he loves music and he would come up to our apartment and eat with us. That‘s how I got connected with them … I used to wish I got here when I was younger. It would be much easier to learn English. But I’m glad now, because I can be a bridge for the community. I moved here and started 9th grade again … so I was like 21 already when I graduated high school! And then I was shy. I worried people would laugh, and I never talked back to teachers! Working with Spero helped me so much. .. I have seen [the anti-Asian American violence] on the news and I was very surprised. I think very great people live in Oklahoma City.”

© UNHCR/Nick Oxford

Why the month of May?

On May 7, 1843, the first Japanese immigrant arrived in the United States. In May 1869, the “Golden Spike” was driven into the ground, completing the first transcontinental railroad. Chinese accounted for almost the entire workforce on the historic railroad, but received no recognition.

Ghost Stories

Joseph Allen Ruanto-Ramirez

San Diego, California

When Joseph, 35, came to the United States as a child, his mother immediately sought to immerse him in language classes so he could blend in – with other Filipinos. As members of an indigenous community, Joseph’s family had to learn the national language of the Philippines, Tagalog, in schools. His mother enforced the language at home for fear of not being able to find community with others from the Philippines in their new country.

“Can we be part of that community which has seen us as an ‘other’ back at home?”

“I think that’s constantly in the mind of many ethnic and indigenous minorities that come to the United States: ‘Can we be part of that community which has seen us as an ‘other’ back at home?’”

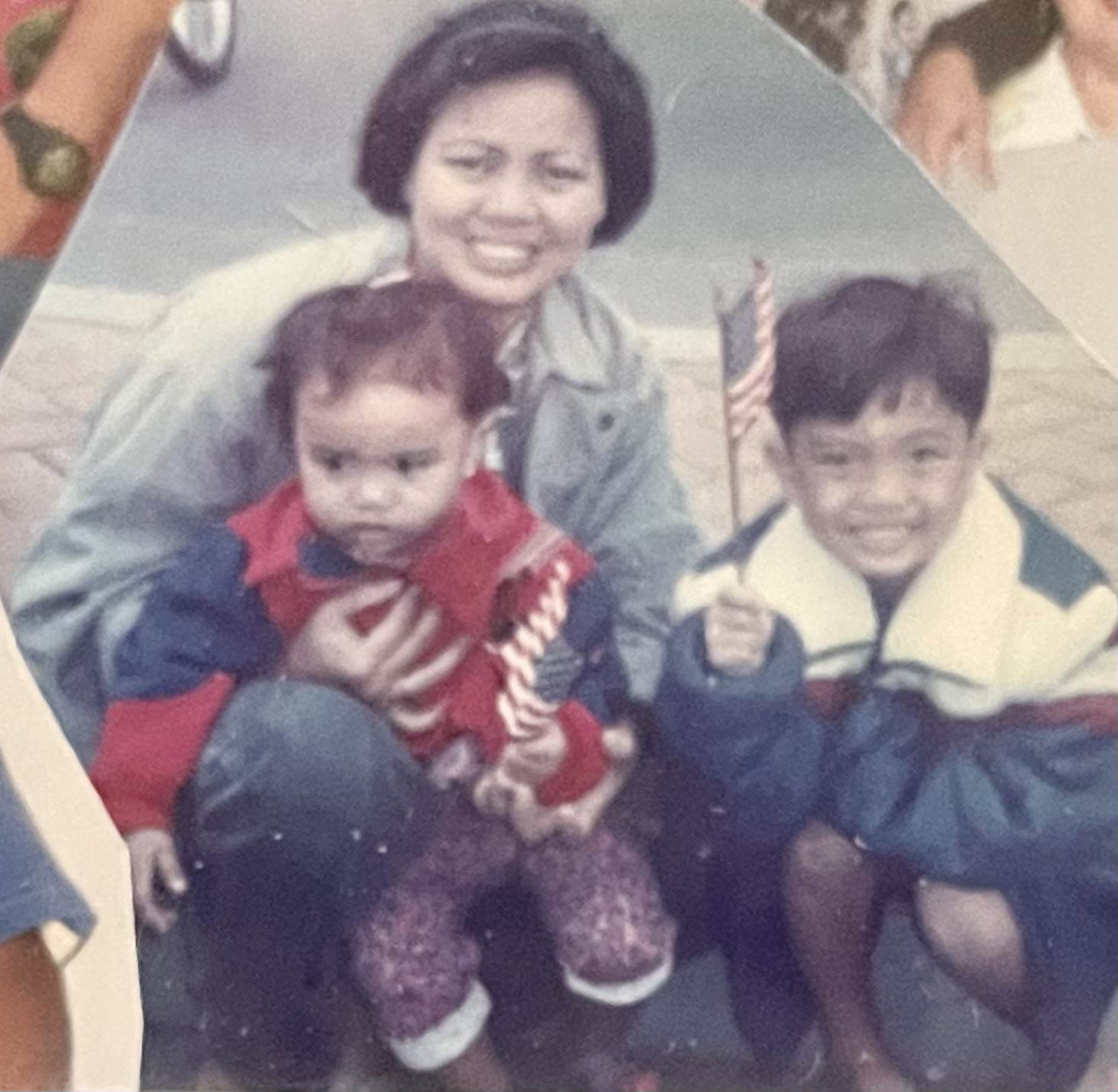

Joseph and his mom, Josephine, and sister, Jhelen Marie, at their first Fourth of July parade in downtown Long Beach, California. Photo: Courtesy Joseph Allen Ruanto-Ramirez

“Racism is seeing another community ‘as a monster, something you need to be scared of.’”

Today, Joseph is a PhD candidate in cultural studies at the Claremont Graduate University. He researches and teaches the complexities of identity, often drawing on his personal experience as a “queer, Indigenous Asian American refugee” – as he has described himself. When Joseph explains his work to his mother, he tells ghost stories – relating his work in the study of race, gender and sexual identity, and ethnicity to tales his mother grew up hearing back in the Philippines. Racism, he explains to her, is like seeing another community “as a monster, something you need to be scared of.” A lot of their talks, including those about his sexual identity, begin with finding a common language. His mother’s consumption of U.S. television comedies about gay life provided her the English language terms and American context for him to discuss his queer identity.

“Sometimes the activism and the hard conversations don’t happen in the classroom, but at the dinner table – with our family, with our friends. Those are the moments when memories and trauma and understandings and misunderstandings have to come into play, without politics, without books, without awkward rhetoric. It’s literally, ‘how do we have a conversation in our own home and understand each other?’”

© UNHCR/Kristie-Valerie Hoang

“Nearly 75% of respondents in our survey say white Americans are ‘well respected’ or ‘somewhat respected.’ By contrast, only about 34% say Asian Americans are respected in our country.”

– The STAATUS Index Report by LAAUNCH.org, May 2021, based on a representative sample of 2,766 US residents aged 18 and over.

Questions

Vimala Phongsavanh

Woonsocket, Rhode Island

Growing up, Vimala watched her parents and other former refugees from the Laotian American community organize. For every birthday or wedding, retirement or funeral, each person had their list of names and would collect money to pay for the event. When Vimala, then 22, ran for local office in 2011, she enlisted her parents to help gather the signatures she needed to run. She went to the Board of Canvassers with a list of 100 new voters and handed it to the man at the front desk. He took a look, and asked her if she had gone to Viet Nam to get the signatures.

For every birthday or wedding, retirement or funeral, each person had their list of names and would collect money to pay for the event.

“But then he could see my face…and he’s like, ‘I’m just kidding,’” said Vimala, who was born and raised in Woonsocket. “If I had that experience, I can’t imagine my mom going there and trying to register to vote. That keeps fueling the fire. I won that election by 60 votes.”

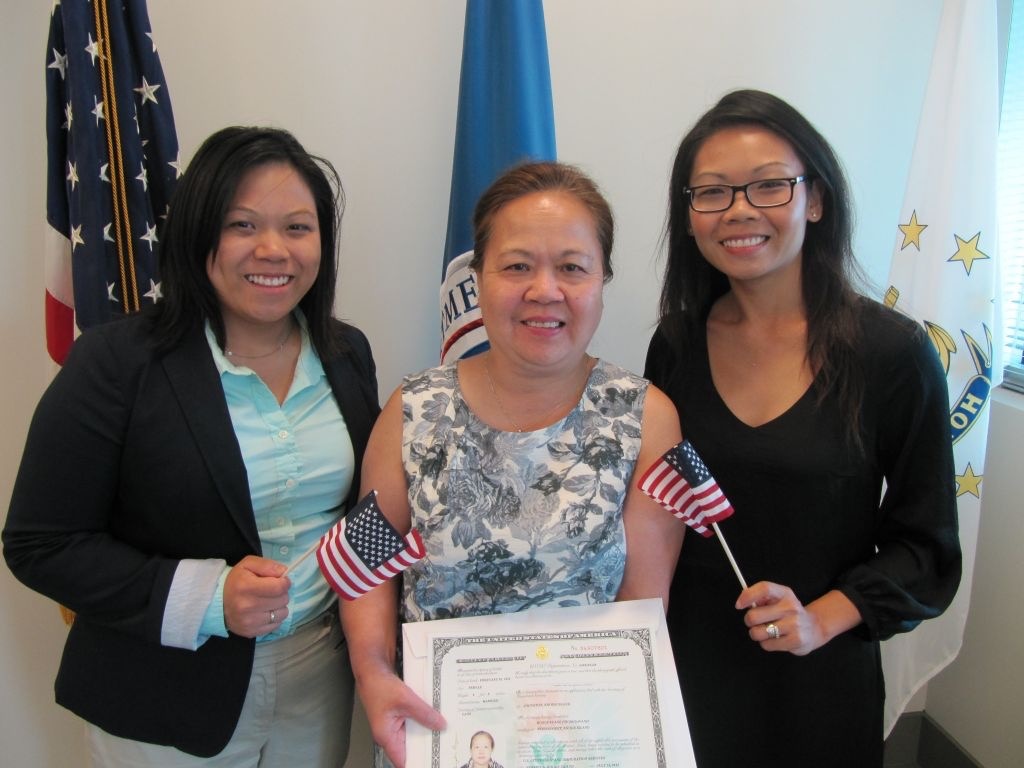

Vimala with her sister, Sengdara Sengsavang, at her mom’s citizenship ceremony. Photo: Courtesy Vimala Phongsavanh

Vimala, 34, now works as an organizer at the Congressional Progressive Caucus Center in Washington. She drums up support for policies such as data disaggregation. The idea has gained widespread support as a way to better direct government resources – especially given the “model minority” myth that perpetuates the notion that Asian Americans are a homogenous and relatively well-off group.

Vimala’s work overlaps with her passion project, which is learning her family history. It’s a slow process that began after a stint doing public service in Boston’s Chinatown after she graduated from college. One of the young immigrants asked about her family’s experience. She had never asked her parents many questions about the past, so she initiated a new phase in their relationship.

“I’ve always wanted to know what my mom’s dreams are.”

“I would just ask tiny things … If [mom] was cooking it was, ‘how did you learn how to cook this?’ and it would turn into a story about her mom or grandma. And then it was also translating words like sun, which meant camp. There’s another word [my parents used] for reeducation camp … These were words that I would grow up hearing but not connecting what they meant, or just not having that much of an interest.

I do remember a moment where I was like, wow, this is a lot – learning all this information about how my family got here, the trauma and the history of violence in Laos and even the violence we face here as refugees. I’ve always wanted to know what my mom’s dreams are. I’ve never asked [my parents] and I feel like they would say, ‘just you being able to take care of yourself.’”

© UNHCR/Robin Winchell

In January, President Joe Biden signed the Memorandum Condemning and Combating Racism, Xenophobia and Intolerance Against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the United States. It declared, “the Federal Government must recognize that it has played a role in furthering these xenophobic sentiments.”

Memories

Kathy Tran

West Springfield, Virginia

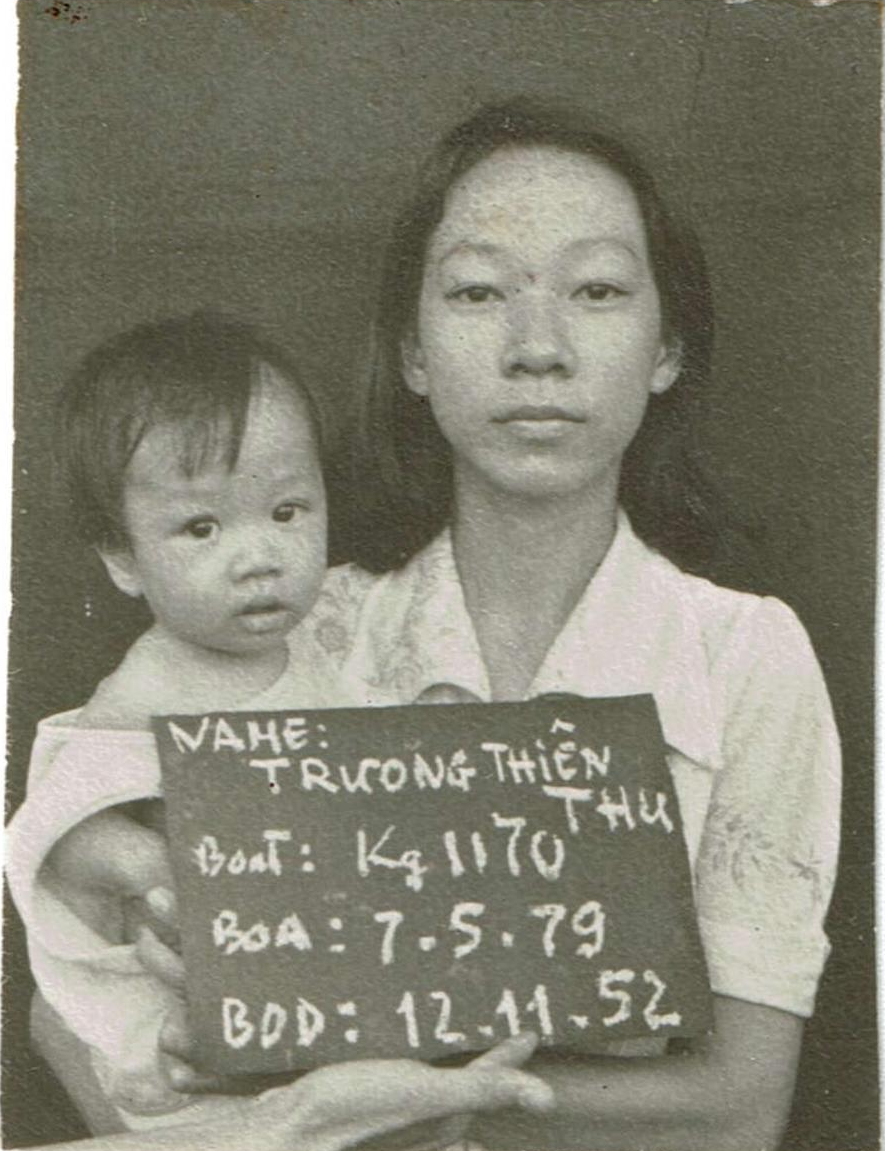

Kathy, 42, recites every detail of her parents’ escape from Viet Nam in 1979. The tears and pain well up as though she were remembering it – even though she was only seven-months-old. The night so dark her mom could barely tell the sky from the sea when trying to find the boat. The terror as a wedding ring hidden in a metal canteen jingled just as pirates boarded. The boat breaking apart as they reached the island off of Malaysia.

“My story is really the story my parents have told, and their memory.”

“I was so little, and I became so dehydrated and sick on the ship, my mother thought they were going to have to bury me at sea,” Kathy said. “My story is really the story my parents have told, and their memory…”

Seven-month-old Kathy in her mother’s arms at the Pulau Bidong refugee camp in Malaysia. Photo: Courtesy Kathy Tran

Kathy now serves as a member of the Virginia state legislature. Her mom made the first donation to her campaign when she ran in 2017. Her father came to babysit while Kathy went door-to-door introducing herself. Kathy told people her story, her parents’ story, of escape and rebuilding. People shared their own tales. Some were immigrants or refugees who also found a new life in the United States. Others had served in the war in Viet Nam. Others remembered their churches sponsoring Southeast Asian refugees.

In the four years since the election, Kathy has struggled to process the rise in violence and discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islanders and other groups – as a politician, an Asian American refugee, and as a parent raising five children in the Jewish faith she shares with her husband.

“Nobody risks their lives and their children’s lives because life back at home is so easy.”

“I think a lot about these issues through the lens of what I am going to talk to the kids about … When I read about what’s happening at our southern border, when I read about what’s happening across the Mediterranean, I can’t help but think about the decisions my own family made. Nobody risks their lives and their children’s lives because life back at home is so easy. And I believe that there is a whole heck of a lot of hope and justice and opportunity for everybody and I hope that we recognize that – that we affirm that with each other and particularly for refugees who are fleeing persecution. Sometimes I imagine the ocean floor full of these bones of the people who have not made it all pointing in the direction of hope. I think we have to honor that.”

© UNHCR/Ashley Le

People from Asia, and in particular Southeast Asia, represent the largest refugee group ever to resettle in the U.S. After withdrawing from the war in Viet Nam, the Americans helped up to 140,000 Vietnamese leave the country and resettle in the United States. But many more Vietnamese, as well as people from Laos, and those escaping Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia, soon sought refuge. In all, roughly 3 million would be forced to flee in over the next two decades.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, worked closely with governments in Asia and elsewhere during this time to help those who sought safety. The organization launched anti-piracy and rescue-at-sea missions as tens of thousands of Vietnamese – often placing themselves in the hands of smugglers – attempted to reach other southeast Asian nations by boat. Statistics from UNHCR painted a horrifying picture. In 1981 alone, 452 boats arrived in Thailand carrying 15,479 refugees. Pirates had attacked 349 of the boats an average of three times each. Reports showed that 578 women had been raped, 228 abducted and that 881 people were dead or missing.

The U.S. opened its doors to the Vietnamese escaping the war and the conflicts that followed. The newly arrived Vietnamese thrived, despite arriving during a recession. By 1982, their rate of employment surpassed that of the general population.

Today most refugees arriving from Asia come from Myanmar. More refugees from Myanmar have been resettled in the U.S. in the last decade than from any other country with the exception of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Most are fleeing ethnic and religious persecution.

“Violent and deadly attacks against Black, Brown, Asian and Indigenous people, toxic language, and daily and sustained racially charged acts have rightly forced painful – but necessary – conversations to re-examine prejudice, privilege, the way we view the world, and most importantly how we act.”